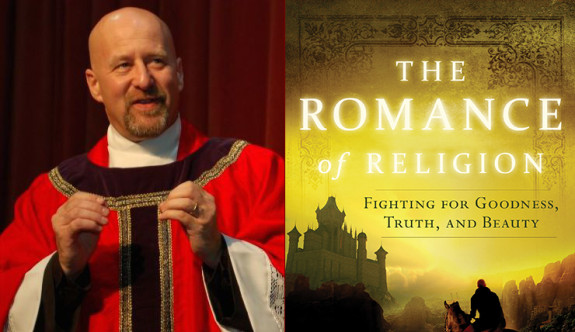

Romance and religion aren’t two words that most people normally associate, but Fr. Dwight Longenecker does. The witty and imaginative priest just released a new book titled, The Romance of Religion: Fighting for Goodness, Truth, and Beauty (Thomas Nelson).

Fr. Dwight recently sat down with me to discuss Jesus, adventure, myth and more.

BRANDON: You introduce your new book, The Romance of Religion, by saying Jesus’ table-turning episode was the key to your own life turning upside-down. How did this happen?

FR. DWIGHT LONGENECKER: Someone has said “the gospel is only good news when it is subversive.” As religious people we often hear this and think that it involves some sort of political activism and the revolutionary spirit. However, the gospel is subversive in more ways than simply societal revolution. To revolt is to revolve, and revolution means not only turning over the tables, but turning over the established, comfortable way of the world. It means to stand on our heads and see the world in a new way. The gospel should always challenge our preconceptions, our prejudices, our bigotry, and bias.

FR. DWIGHT LONGENECKER: Someone has said “the gospel is only good news when it is subversive.” As religious people we often hear this and think that it involves some sort of political activism and the revolutionary spirit. However, the gospel is subversive in more ways than simply societal revolution. To revolt is to revolve, and revolution means not only turning over the tables, but turning over the established, comfortable way of the world. It means to stand on our heads and see the world in a new way. The gospel should always challenge our preconceptions, our prejudices, our bigotry, and bias.

The Romance of Religion takes this and runs with it. It calls for us to be spiritual conquistadors, chevaliers of the spirit, somewhat foolish Don Quixotes setting out to rescue the fair maiden of beauty, tilt at the giant windmills of hypocrisy and pride, and to be so good that we’re bad. In other words, we are agents of contradiction—living prophetic signs of trouble for those who are dozing in their worldliness.

BRANDON: In your new book, you repeatedly describe the Christian life as an adventure and as a romance, which may seem strange to many people. How do these adjectives fit?

FR. DWIGHT: I’m very interested in the storyline of the mythic hero. In Joseph Campbell’s “mono myth”—the one myth to rule them all—the hero is first seen in his ordinary world. Then he hears the call of adventure, refuses the call then sets out on a journey into the unknown to battle as yet unseen enemies and overcome the darkness. Within that classic story he fights for beauty in the form of the fair maiden, and attains some great treasure, which he brings back for the salvation of his people. This is the pattern not only of all the classic myths, and of great literature, but also of all the great sagas in the Old Testament, the pattern of the gospel, and the pattern of the lives of saints.

Staying at home is not an option.

BRANDON: You write, “The Catholic Church has many problems, but being respectable is no one of them.” What do you mean by that?

FR. DWIGHT: By “respectable” I mean respectable in the world’s eyes. One of the truths that helped me convert from Anglicanism to Catholicism was the fact that Anglicanism was the “established church”. Her bishops were appointed by the Prime Minister on behalf of the Queen. Her bishops had seats in the House of Lords. Anglicans were part of the respectable establishment, and it seemed to me that this was not what the church should be. Instead of being interwoven with the systems of power in the world, it should be “in the world, but not of the world”. It was to be respected, but not respectable.

The Catholics, on the other hand, were not established. In England, for hundreds of years they had been persecuted severely. This felt authentic to me. Then when I investigated the countries where Catholicism seemed to be the established church like France, Italy, and Spain, even there I discovered, as I read history, that the course of true love between the governments and the church in those countries never did run smooth. Revolutions and subterfuge were always simmering and for many reasons the Catholic Church—even when she was powerful in worldly terms—was at her best when she was challenging the system rather than supporting it.

BRANDON: Twentieth-century English writers like C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and G.K. Chesterton wrote about doctrine with the romantic verve you reintroduce through this book, but we haven’t really seen that for the last hundred years. Why not?

FR. DWIGHT: I’m actually not sure I agree with you about that. Those of us who love Lewis, Tolkien, and Chesterton view their day with nostalgia, but we’ve got some great writers from the next generation here in the United States. Flannery O’Connor, Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, and Walker Percy come to mind. Presently I think Dean Koontz and Michael O’Brien are making significant contributions, but it takes time for the classics to emerge. One of the problems with the contemporary scene is that startlingly good writers are hard to find because they take time to mature and to develop an audience.

I do agree, however that there is a certain lack of “bite” in many contemporary religious authors. Modernism has watered down the wine and tamed the lion. Consequently, many of those who do write from a standpoint of orthodoxy do so with an unattractive combative tone and accusatory emphasis. The spiritual warrior needs to be cheerful and confident. We need to wield the sword, but with a feather in our hat and a spring in our step. This is why I find the French hero Cyrano de Bergerac so attractive. He battles his foes while composing a poem and sacrifices all while quoting a sonnet.

BRANDON: You agree with C.S. Lewis that Christianity is the true myth, the consummation of all the great fairy tales and stories. How is this so?

FR. DWIGHT: I am convinced that all the great stories find factual fulfillment in the stories not only of the gospels, but of the whole of the Old Testament. I am intrigued to imagine that the Cinderella story, for example, (in which the poor, humble maiden married the Princely Lord and lives happily ever after) comes true in the stories of Isaac and Rachel, Ruth and Boaz, and ultimately in the Annunciation. The story of the rejected brother who turns out to the be the savior echoes in many major myths, in many cultures. There it is in the murder of Abel, the saga of Joseph, the rejection of Elijah, and then in the passion of Our Lord. The story of salvation from Genesis to Revelation is a fulfillment of all the great myths, legends, and tales told in many ways through many cultures but in the Old and New Testament they come true in the lives of real people in history.

The final lesson is if they came true in the history of the Jewish people, and in the history of the lives of the saints, then they may also come true in our own lives if we live by faith.

Critics of Christianity might protest, “But it is all a fairy tale!” I would reply, “Of course it is a fairy tale! Through our religion we don’t just tell a fairy tale, we live the fairy tale. In Christ we can go on the heroic journey. We can find true love’s kiss. We can find the great treasure of eternal life hidden in the field. We can be the hero who saves others, fights for the fair Maiden Mary, battles with the dragon of lust, greed, and death and goes on to win the victory. Just as the fairy tales, myths, and legends “became flesh and dwelt among us” in Christ, so they come true in our own lives if we are willing to embark on that great adventure.

Follow Fr. Dwight’s writing at his blog, Standing On My Head and be sure to pick up his great new book, The Romance of Religion.

If you liked this discussion you’ll find several more on my Interviews page. Subscribe free via feed reader or email and ensure sure you don’t miss future interviews.