Over the centuries, millions of people have been captured by the story of St. Augustine. The brilliant young orator, seeking Truth in many philosophies, found it in the Catholic Church and became the most famous convert in history. His whole journey is recounted in his spiritual autobiography, The Confessions, which is a classic by any measure. Even many unbelievers praise it, a fact signaled by its inclusion in the mostly-secular Great Books of the Western World.

(If you’re looking for a copy, Ignatius Press just published a new edition as part of their Ignatius Critical Edition Series, edited by Joseph Pearce. It features the acclaimed English translation by Sister Maria Boulding, O.S.B., along with extra annotations and essays, all for roughly $8.)

My wife and I read through The Confessions together a few months ago and were deeply moved. So much so that, being pregnant with our third child, we decided to name him “Augustine.” So we were especially excited to see a new full-length feature movie on the saint titled Restless Heart.

The title, of course, comes from Augustine’s classic line on the first page of The Confessions:

“You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it rests in you.“

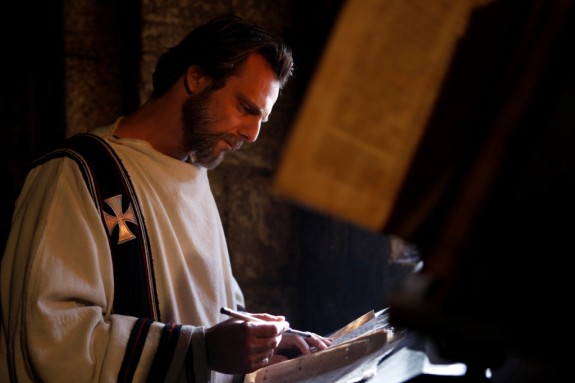

Restless Heart follows Augustine through this restlessness. We watch him as a youth, pursuing mastery in the art of rhetoric, convinced that the fame and power which flow from it would eventually satisfy him. When that failed, he turned to physical pleasure. He satiated his lusts through sex and partying, yet those failed him too. From there he drifted through several Gnostic philosophies, including Manichaeism, a Christian heresy. And again, nothing satisfied.

Even after pouring himself into fame, power, money, pleasure, and cults he was still left panting for more. It wasn’t until he encountered Christ and his Church that he realized how empty his indulgences were. Only then were all his longings and all his seeking fulfilled.

Even after pouring himself into fame, power, money, pleasure, and cults he was still left panting for more. It wasn’t until he encountered Christ and his Church that he realized how empty his indulgences were. Only then were all his longings and all his seeking fulfilled.

While Restless Heart depicts this whole search, the film accentuates two aspects better than the book. First, the power of rhetoric in Augustine’s life. At the beginning of Restless Heart, we see Augustine begging Microbius, the top orator and lawyer of his day, to teach him the art of oration. At first, Microbius balks. Augustine is unfocused and unskilled, and Microbius is too busy to train him. But Augustine refuses to give up. He studies hard, continues to beg Microbius, and the master eventually gives in. He begins teaching Augustine how to persuade through words, how to sway judges and jurors through appealing to emotion. Microbius openly admits to twisting the truth to his advantage.

Once he tastes this power, Augustine becomes drunk on it. He works hard and becomes one of the world’s greatest orators. Like his master, he sways courts and even convinces a jury to acquit a man whose guilt is later proved true.

By request of the emperor, Augustine is summoned to Milan to become the the emperor’s personal orator. And there he meets a pivotal figure in his conversion: St. Ambrose, the bishop of Milan. Augustine is immediately taken aback by the bishop’s intelligence and rhetorical skill. He had rarely encountered anyone whose genius could match his own, much less a Christian bishop. Ambrose, though, seems to use rhetoric in a different way—a more noble way. He doesn’t twist words nor pretend to create his own truth. Instead Ambrose tells Augustine that men never find the truth through words. “They must,” he says, “let the Truth find them.”

And so it does. It takes many more months, but Augustine eventually relents and lets this objective truth enrapture him, within and without. He gives up his lusts, he becomes baptized, and grows into the most ardent, articulate defender of Christianity of his day, in no small part due to his early rhetorical studies.

And so it does. It takes many more months, but Augustine eventually relents and lets this objective truth enrapture him, within and without. He gives up his lusts, he becomes baptized, and grows into the most ardent, articulate defender of Christianity of his day, in no small part due to his early rhetorical studies.

Restless Heart exhibits the profound transfiguration that occurs when gifts once used negatively against God are redeemed and then used for him (one thinks of St. Paul’s own pen, for example.) In Augustine’s case, his gift was rhetoric, first developed and used for ill. But when untwisted it became a powerful tool used in the service of God.

Second, the movie beautifully highlights the role of St. Monica, Augustine’s mother. Almost all we know about her comes from Augustine’s own Confessions. And even there, the details are scant. Like Mary in Scripture, Monica rarely speaks directly. She instead hovers on the periphery, praying in the background for her son.

The film, however, places her front and center. It showcases her resilient, tear-drenched prayers which influence Augustine as much as Ambrose’s intellectual appeals. She’s featured almost as much as her son, a testament to her profound role in his conversion.

In the end, Restless Heart is the most epic saint biography ever produced. The film stands above the recent flow of sappy, low-budget Christian films and is more in line with The Passion of the Christ. With gifted acting, a moving score, and masterful screenwriting, it breathes life into three of the Church’s greatest and most iconic saints: Augustine, Ambrose, and Monica.

If you’re attending next week’s Catholic New Media Conference/Catholic Marketing Conference in Dallas, The Maximus Group is hosting a free preview screening of the film on Wednesday night at 8:45pm!

While the film isn’t screening nationally yet, you can host a screening in your own area. To learn more about how you can bring Restless Heart to a theater near you, contact the Maximus Group either by phone (877-263-1263) or e-mail (RestlessHeart@MaximusMg.Com.) You can also learn more at www.RestlessHeartFilm.com.

(It should be noted that Restless Heart doesn’t whitewash Augustine’s pre-conversion past. It depicts his promiscuity and partying, which may make the film unsuitable for young children. If rated, I’m guessing it would earn a PG-13.)