One of the big highlights of last weekend’s Defending the Faith Conference was meeting Dr. Peter Kreeft. I got to share many conversations with the wise, witty, and wondrous philosopher. We discussed everything from C.S. Lewis and surfing, to atheists, J.R.R. Tolkien, Jewish mystics, and of course books.

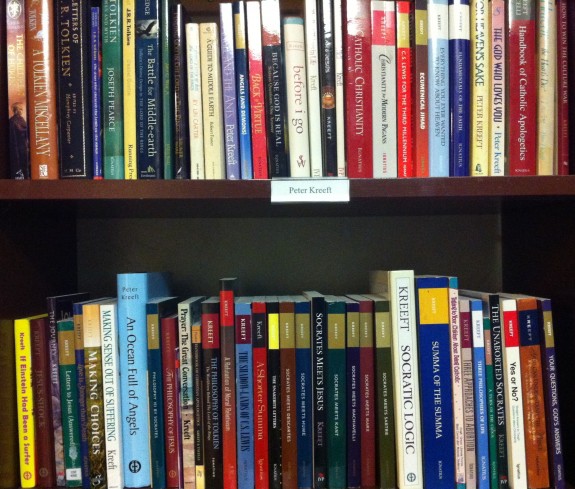

While discussing our current reads, I mentioned I’m into several introductory philosophy books. “Which ones?” he said, his eyes lighting up. “The Socratic dialogues, some books by Mortimer Adler, your own titles on logic and St. Thomas Aquinas, and William Lane Craig and Dr. Ed Feser on metaphysics.”

In reply, Peter rifled off several more recommendations. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a pen but I asked if he could email me the titles. To my surprise, a couple days later, I received not an email but a letter in my mailbox—what Peter calls “realmail”—containing the following lists. They’re from his forthcoming series, Socrates’ Children (St. Augustine’s Press), which traces the history of philosophy in four volumes and focuses more on “the Big Ideas” than on the big philosophers themselves.

The book recommendations were so helpful I wanted to share them here. Many of these titles are in the public domain and available free online. But I’ve linked to the best translation and edition available on Amazon. So if you’re a budding philosopher searching for a solid reading plan, look no further. Enjoy!

(For more recommendations, also see my post on Fr. Barron’s Recommended Books on Philosophy 101.)

Many people have asked me for a recommended booklist for a teach-yourself philosophy course. Many beginning philosophy teachers have asked me for a similar list for an introductory course in philosophy.

I know of no more effective way to teach philosophy, to yourself or others, than the apprenticeship to the masters that is called “The Great Books.” The “canon” of Great Books is certainly not fixed, or stuffy, or irrelevant to today’s world. The list is pragmatic: it is a list of what has “worked.”

Based on my own experience of what “works,” i.e. what (a) is comprehensible to beginners and (b) inspires them to think and perhaps even to fall in love with philosophy, here is my list.

There is a primary list and a secondary list for each of the four volumes of Socrates’ Children, i.e. for each of the four periods in the history of philosophy. For a high school course, one of these eight lists would seem to fit into one semester; fer a college course, two; and for a graduate course, three or four. The lists are deliberately short and selective; far better to spend much time with a few great friends than a little time with many little ones.

Ancient Philosophy, Basic List:

- Solomon, Ecclesiastes (cf. Peter Kreeft, Three Philosophies of Life)

- Plato, Meno and Apology

- Plato, Republic, excerpts (if you use the W.H.D. Rouse translation (Great Dialogues of Plato) and mentally divide each book into 3 parts, A, B and C, you could cover Book I, IIA, VB through 7A, 9C, and Rouse’s helpful summary of the rest.

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, select your own excerpts, but be sure to cover Books I and VIII

- Plotinus, On Beauty

Ancient Philosophy, Additional List:

- Parmenides’ poem

- The rest of Plato’s Republic

- Plato, Gorgias

- The rest of the Nicomachean Ethics

- A secondary source summary of Aristotle, either Mortimer Adler’s Aristotle for Everybody (easy) or Sir David Ross’s Aristotle (intermediate)

Medieval Philosophy, Basic List:

- St. Augustine, Confessions 1-10 (F.J. Sheed translation)

- Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy (published by Hackett)

- St. Anselm, Proslogium

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, at least I,2,3 (“On God’s Existence”) and I-II,2 (“On Things in which Man’s Happiness Consists”). These and more, with explanatory notes, are included in my A Shorter Summa.

Medieval Philosophy, Additional List:

- St. Bonaventure, The Journey of the Mind to God

- Aquinas, more of the Summa Theologiae. My Summa of the Summa anthology is 500 pages, with many footnotes

- Nicholas of Cusa, Of Learned Ignorance

Modern Philosophy, Basic List:

- Machiavelli, The Prince

- Renes Descartes, Discourse on Method

- David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

- Immanuel Kant, Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals

Modern Philosophy, Additional List:

- Rene Descartes, Meditations

- Gottfried Leibnitz, Monadology

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, excerpts

- (Blaise Pascal’s Pensées could also be included here; see below)

Contemporary Philosophy, Basic List:

- Blaise Pascal Pensées (or my Christianity for Modern Pagans)

- Jean-Paul Sartre, Existentialism and Human Emotions

- William James, “What Pragmatism Means” and “The Will to Believe”

- Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto

- C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man

Contemporary Philosophy, Additional List

- John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism

- Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy

- Alfred Jules Ayer, Language, Truth and Logic

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

- G.K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

APPENDIX I: A bibliography of books on the history of philosophy by the author:

- Solomon: Chapter 1 of Three Philosophies of Life (Ignatius Press)

- Shankara: “The Philosophy of Religion” (recorded lectures)

- Buddha: op. cit.

- Confucius: op. cit.

- Lao Tzu: op. cit.

- Socrates: Philosophy 101 by Socrates: An Introduction to Philosophy via Plato’s “Apology” (Ignatius Press, St. Augustine’s Press)

- Plato: “The Platonic Tradition” (recorded lectures)

- Aristotelian logic: Socratic Logic (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Jesus: The Philosophy of Jesus (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Jesus: Socrates Meets Jesus (lnterVarsity Press)

- Jesus: Jesus Shock (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Muhammad: Between Allah and Jesus (InterVarsity Press)

- St. Thomas Aquinas: “The Philosophy of Thomas Aquinas” (recorded lectures)

- St. Thomas Aquinas: A Shorter Summa (Ignatius Press)

- St. Thomas Aquinas: Summa of the Summa (Ignatius Press)

- Machiavelli: Socrates Meets Machiavelli (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Blaise Pascal: Christianity for Modern Pagans (Ignatius Press)

- Rene Descartes: Socrates Meets Descartes (St. Augustine’s Press)

- David Hume: Socrates Meets Hume (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Immanual Kant: Socrates Meets Kant (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Karl Marx: Socrates Meets Marx (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Søren Kierkegaard: Socrates Meets Kierkegaard (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Sigmund Freud: Socrates Meets Freud (St. Augustine’s Press)

- Jean-Paul Sartre: Socrates Meets Sartre (St. Augustine’s Press)

- J.R.R. Tolkien: The Philosophy of Tolkien (Ignatius Press)

- C.S. Lewis: C.S. Lewis for the Third Millennium (Ignatius Press)

- Modern philosophers systematically argued with from a Thomist perspective: Summa Philosophica (St. Augustine’s Press)

- The history of ethics: “What Would Socrates Do?” (recorded lectures)

APPENDIX II: Recommended histories of philosophy

This short and selective list of histories of philosophy does not duplicate this one but have somewhat different ends.

1. Frederick Copleston, SJ. has written the most clear and complete multi-volume history of Western philosophy available, with increasing detail as it becomes more and more contemporary. It is not exciting, dramatic, or “existential” but it is very fair, clear, logical, and helpful.

2. Will Durant’s The Story of Philosophy is charmingly and engagingly written, though very selective and personally “angled” towards “Enlightenment” thinkers.

3. Bertrand Russell, a major philosopher himself, has written a very intelligent, elegant, and witty little History of Western Philosophy from the viewpoint of an atheist, semi-skeptic, and semi-materialist.

4. Francis Parker’s one volume history of western philosophy up to Hegel, The Story of Western Philosophy, neatly structures this history via the theme of the one and the many.

5. Mortimer Adler’s Ten Philosophical Mistakes is not a complete history but a selective diagnostic treatment of key errors in modern philosophy.

6. Etienne Gilson’s The Unity of Philosophical Experience does the same, finding reductionisms of philosophy to one of the sciences as a nearly universal modern error.

7. William Barrett’s Irrational Man, though purportedly only an introduction to Existentialism, has engaging chapters on pre-existential philosophers from an Existentialist viewpoint, and the best one-chapter summaries of Nietzsche, Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and Sartre in print.

8. Richard Tarnas’s The Passion of the Western Mind is indeed “passionate” and existential, and focuses on the more general surrounding historical and cultural events and influences.

9. Samuen Enoch Stumpf (Socrates to Sartre and Beyond) and Robert Solomon (A Short History of Philosophy) have both produced good one-volume histories of Western philosophy.

Most introductory philosophy textbooks today are not “Great Books” histories but anthologies of recent articles about systematic, logical issues, most of which are relatively thin, dry, dull, technical, and lacking in “existential” bite as well as style. They have their place, but students, especially in the Humanities, will find histories of philosophy much more interesting for the same reason they find stories more interesting than formulas, and dialogs more interesting than monologs. That was Plato’s genius. His Socratic dialogs remain the single best introduction to philosophy ever written.

Thus we end, as we begin, with Socrates. Welcome to the commodious and contentious family of his children.