According to G.K. Chesterton, there are only two reasons to join the Catholic Church. First, because you believe it to be the solid objective truth, whether you like it or not. Second, because you seek liberation from your sins.

In 1922, Chesterton himself followed these reasons right to Rome, embarking on an adventure he would never tire of sharing. It was through becoming Catholic that Chesterton discovered orthodoxy to be far from stifling, stuffy, boring, or dry. He began to see it as both vibrant and free.

Maybe the twentieth century’s most notable Catholic convert, Chesterton was also one of its wittiest, wisest, most whimsical men. He had a gift for seeing our upside down world right side up. In fact one Chesterton disciple calls him “The Apostle of Common Sense.”

Chesterton was also a prolific writer, before and after his conversion, penning more than 80 books, 300 poems, 4,000 essays, and many different plays. He contributed regular articles to a number of newspapers and even wrote entries for the Encyclopedia Britannica.

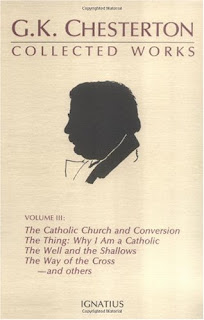

Ignatius Press has compiled many of these writings into a definitive series of Collected Works, and so far they’re up to 36 volumes. Volume 3 of Chesterton’s Collected Works (Ignatius Press, paperback, 550 pages) includes six essays focusing exclusively on his decision to become Catholic:

- Where All Roads Lead

- The Catholic Church and Conversion

- Why I Am a Catholic

- The Thing: Why I Am a Catholic

- The Well and the Shallows

- The Way of the Cross

In all of his writings, Chesterton twirls words like a baton, effortlessly spinning simple phrases into ironies and paradoxes. It doesn’t take long to discover that reading Chesterton is a lot like riding a roller coaster. You feel tugged and pulled and yanked and you don’t know what’s coming up next.

A priest-friend of mine said that “reading Chesterton is like watching an epic tennis match”. He jerks your mind’s eye left then right then backward then forward and it’s all you can do just to watch the ball fly.

But when the roller coaster stops–when the ball hits the ground–a content smile creeps across your face. You may not remember how you got here, but you do know where you’ve ended up. After a whirlwind journey, you’ve landed on safe ground. And you know you’re standing right side up.

This volume of essays is no exception to that style. Chesterton’s pithy topsy-turviness is on full display:

“When a man really sees the Church, even if he dislikes what he sees, he does not see what he had expected to dislike.”

“If there was no God, there would be no atheists.”

“At least six times during the last few years, I have found myself in a situation in which I should certainly have become a Catholic, if I had not been restrained from that rash step by the fortunate accident that I was one already.”

But the same things that make Chesterton great also make him difficult. He’s so unstructured and off-the-wall that it’s often tough to grasp his arguments. He jumps from one topic to another, his mind clearly outpacing his pen, which can leave you mentally exhausted after just a few essays.

Also, while I did enjoy this volume, I didn’t find it as absorbing as his classic Orthodoxy or his intriguing Fr. Brown mysteries. This disparate collection doesn’t really have a consistent thread or flow to keep you engaged, outside of general Catholic apologetics.

Also, while I did enjoy this volume, I didn’t find it as absorbing as his classic Orthodoxy or his intriguing Fr. Brown mysteries. This disparate collection doesn’t really have a consistent thread or flow to keep you engaged, outside of general Catholic apologetics.

As with most Chesterton, you’re also expected to be familiar with twentieth century politics, philosophy, and culture. If you’re not, many of his quips will fly right over your head. The footnotes throughout the book help fill in some of the gaps, but on many occasions I was still left scratching my head or turning to the Internet for some background information. That’s not a slight on the book–more a critique of the reader–but it nevertheless should be noted.

For those who have already enjoyed multiple course of Chesterton, Volume 3 of his Collected Works is good dessert. However it’s probably not the best appetizer. If you’re looking for a gateway to Chesterton, I would instead recommend one of Dale Ahlquist’s books or Chesterton’s own Orthodoxy.

But for the seasoned Chestertonian–especially one interested in Chesterton’s Catholicism–this wild romp through orthodoxy is intelligent and witty, difficult and fun.