In June 2019, my wife and I flew to England on a pilgrimage to celebrate our tenth wedding anniversary. We spent five days in London and three in Oxford. Our goal was to see and pray at all the sites associated with G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and John Henry Newman, who have each massively impacted our faith and family. Of course, we also wanted to visit beautiful churches and bookstores.

The trip was extraordinary. Though I researched and planned for months, we were still surprised by many unexpected graces and encounters, making an already great trip spectacular.

Much of that was credited to Fr. Michael Ward and Dr. Holly Ordway, longtime friends and among the world’s leading experts on C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, respectively. They were gracious hosts throughout our Oxford leg, and fonts of helpful advice. We shared many good hours and meals.

We were also blessed that my best friend, Fr. Blake Britton, happened to be swinging through England on his way to Italy, so he joined us in Oxford during the last few days of our trip. Walking the streets of England with my wife and friends, gazing on the spires, celebrating Mass in resplendent churches, poring through dusty used bookstores—it was heavenly.

Afterward, I debated whether to share pictures from the pilgrimage. I’m always wary of FOMO and “travel envy,” which many travelogues inspire. But I decided to post them for two reasons. First, I realized lots of people would never have the chance to visit England, but would still enjoy following the pictures. Second, and more importantly, during the months I spent researching this, I found there were few good pilgrimage/tourist guides to Chesterton, Lewis, Tolkien, and Newman sites online, and what's available is typically dated, inaccurate, or incomplete.

So I’m sharing this recap not to stir up envy, but for those who want to take a “virtual” pilgrimage and for those who want to plan their own pilgrimage. I included all the addresses and tour info. This is the guide I wish I had before visiting England. So here we go!

Note: Click photos to open larger versions.

Jump ahead to sections:

G.K. Chesterton

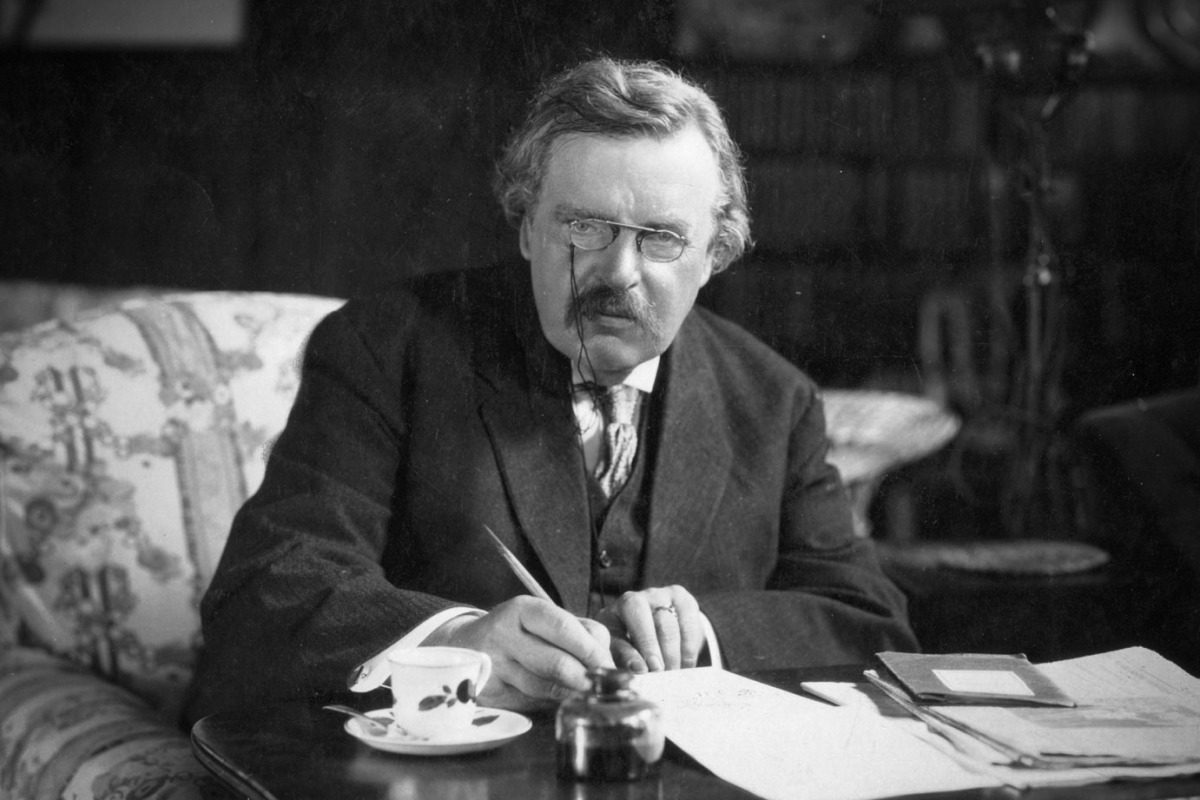

G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936) was an English writer, poet, and journalist, and one of the dominating literary figures in England during the early twentieth century. He was incredibly prolific. Chesterton wrote over 4,000 newspaper essays, 100 books (contributing to 200 more), hundreds of poems (including the epic Ballad of the White Horse), five plays, five novels, and some two hundred short stories, including the detective mysteries featuring Father Brown (the basis for the popular Father Brown series on BBC.)

Chesterton converted to Catholicism in 1922, perhaps the most famous convert of the twentieth century, and is responsible for leading countless others into the Church. Learn more about him at Chesterton.org, especially this piece: "Who is this Guy and Why Haven’t I Heard of Him?"

(Full disclosure: I'm on the board of the Society of G.K. Chesterton, which runs Chesterton.org.)

Early Life

GKC's Birthplace

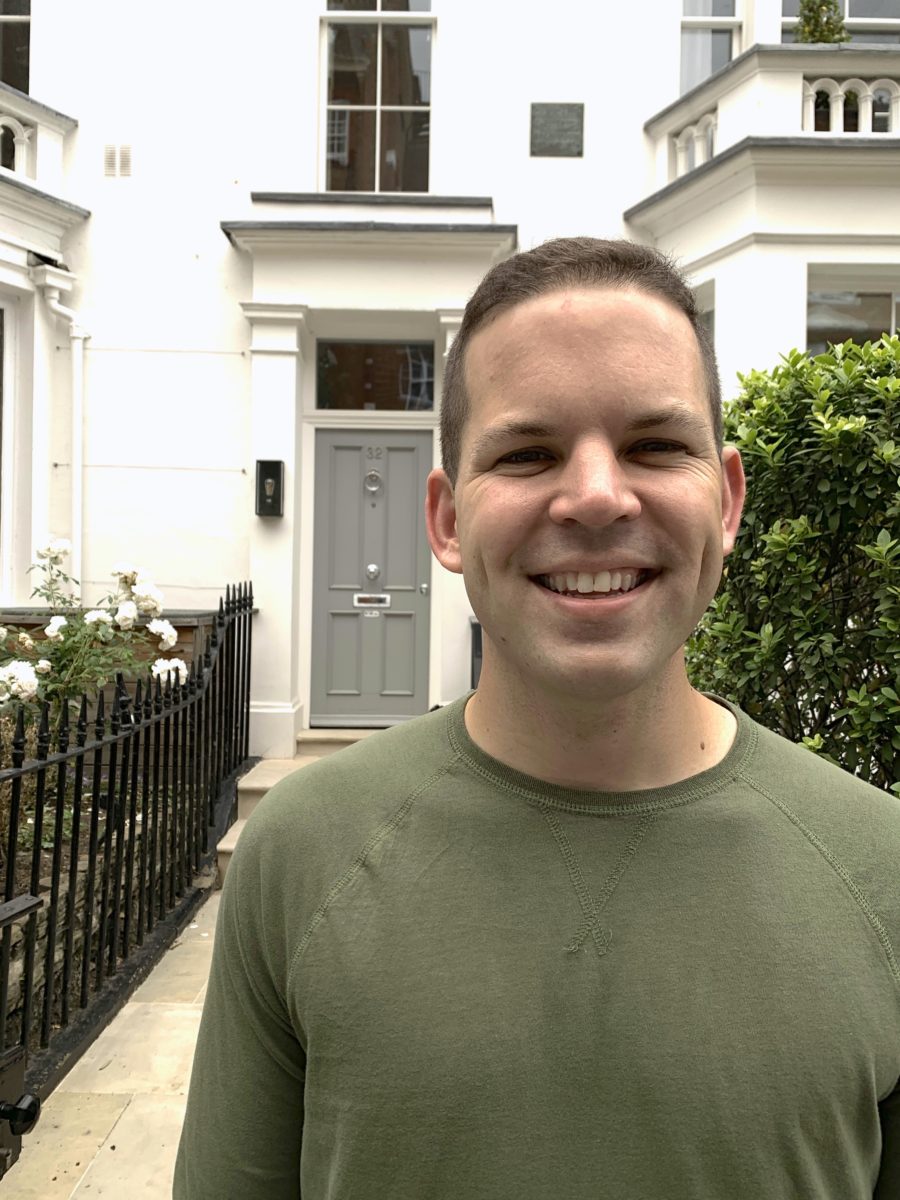

32 Sheffield Terrace, Kensington, London, UK

Chesterton was born in this home and lived here from ages 0 to 5 years old. It's where he first delighted in the toy theater his father built for him, beginning a lifelong fascination with puppets, plays, and small figurines.

A historic plaque sits above the door, reading “Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born here 29th May 1874”.

When we walked by the house, a lady happened to come out the front door, pushing a stroller. We waved hello and pointed at the plaque, saying we were Chesterton fans who had come all the way from America to see this house. She was unmoved. I asked whether she lived there, and she said, “No, I’m just the nanny. The family moved in a few years ago, but they totally redid the whole interior.” I took that as a signal to mean, “I’m not giving you a tour.” But that's fine since the inside must not look anything like what Chesterton would have known.

Still, it was special standing in the place where this man came into the world, where the great lover of childhood first became a child.

GKC's Baptismal Church

Campden Hill, 28 Aubrey Walk, Kensington, London W8 7JG, UK

Chesterton was baptized in St. George’s Anglican Church. The baptismal font dates to a few years before his birth, so I’m guessing it’s the very font in which he became a Christian.

Interestingly, in Chesterton’s boyhood there stood a giant water tower right across the street from this church, which figures prominently in the end of his first novel, The Napoleon of Notting Hill. The water tower was demolished in 1970, though probably not by Adam Wayne.

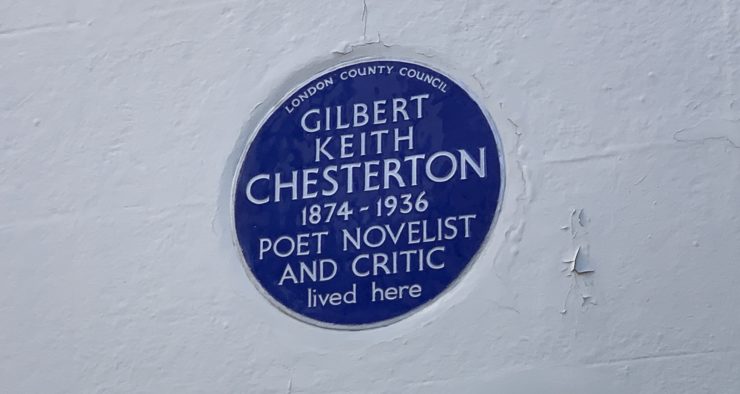

GKC’s Boyhood Home

11 Warwick Gardens, Kensington, London W14 8PH, UK

When Gilbert was five years old, the Chestertons moved a mile or so down the road to 11 Warwick Gardens, and Gilbert lived there until age 25, when he married Frances Blogg.

A historic plaque on the side of the house reads “Gilbert Keith Chesterton 1874-1936 Poet, Novelist, and Critic Lived Here”.

Warwick Gardens was likely a quiet area in Gilbert’s time but today a bustling line of restaurants and shops stretches nearly to the home's doorstep.

St. James Bridge

St James's Park, London SW1A 2BJ, United Kingdom

It was the autumn of 1896, when Gilbert was 22 years old, that he first met Frances Blogg. He fell in love with her instantly. Here’s Gilbert describing their initial meeting:

Once in the course of conversation she [Frances] looked straight at him [Gilbert] and he said to himself as plainly as if he had read it in a book:

If I had anything to do with this girl I should go on my knees to her: if I spoke with her she would never deceive me: if I depended on her she would never deny me: if I loved her she would never play with me: if I trusted her she would never go back on me: if I remembered her she would never forget me. I may never see her again. Goodbye.

It was all said in a flash: but it was all said….

That night, alone in his room, he wrote a poem titled “To My Lady,” celebrating how God made Frances as the pinnacle of his creation. Frances eventually fell in love with Gilbert as well, and their relationship blossomed.

Two years later, on July 21, 1898, Gilbert proposed to Frances on the small bridge in St. James Park. The actual bridge has since been replaced with a modern bridge, but the location is identical.

(If you don't know much about Frances, the quiet pillar upholding Gilbert's whirling genius, read this short profile and then pick up Nancy Brown's excellent biography, The Woman Who Was Chesterton.)

A few hours after proposing to Frances, after he got home that evening, Gilbert sat down and wrote this beautiful letter to his new fiancée:

Dearest Frances,

You will, I am sure, forgive one so recently appointed to the post of Emperor of Creation, for having had a great deal to do tonight before he had time to do the only thing worth doing. I have just dismissed with costs a case between two planets and am still keeping a comet (accused of furious driving) in the ante-chamber.

Little as you may suppose it at the first glance, I have discovered that my existence until today has been, in truth, passed in the most intense gloom. Comparatively speaking, Pain, Hatred, Despair, and Madness have been the companions of my days and nights. Nothing could woo a smile from my sombre and forbidding visage. Such (comparatively speaking) had been my previous condition. Intrinsically speaking it has been very jolly. But I never knew what being happy meant before tonight. Happiness is not at all smug; it is not peaceful or contented, as I have always been till today. Happiness brings not peace but a sword: it shakes you like rattling dice; it breaks your speech and darkens your sight. Happiness is stronger than oneself and sets its palpable foot upon one’s neck.

When I was going home tonight upon an omnibus—I felt pained somehow that it was not a winged omnibus—a curious thing came upon me. In flat contradiction to my normal physical habit and for the first time since I was about seven, I felt myself in a kind of fierce proximity to tears. If you knew what a new weird feeling it was to me you would have some idea of the state I am in.

Another thing I have discovered is that if there is such a thing as falling in love with anyone over again, I did it in St. James’ Park (St. James seems our patron saint somehow—Hall—Station—Park—etc.). I think it is no exaggeration to say that I never saw you in my life without thinking that I under-rated you the time before. But today was something more than usual: you went up seven heavens at a run.

I will tell you one thing about the male character. You can always tell the real love from the slight by the fact that the latter weakens at the moment of success; the former is quadrupled. Really and truly, dearest, I feel as if I never thought you so brave and beautiful as I do now. Before I was only groping (frantically indeed) for my own soul.

I cannot write connectedly or explain my position now; we will have sensible conversation later. I am overwhelmed with an enormous sense of my own worthlessness—which is very nice and makes me dance and sing—neither with great technical charm. I shall of course see you tomorrow. Should you then be inclined to spurn me, pray so. I can’t think why you don’t, but I suppose you know your own business best.

People are shouting at me to go to bed, and they ought to be listened to. It will be their turn to listen soon. Don’t worry about your Mother; as long as we keep right she is sure to be with us.

God bless you, my dear girl.

Yours,

Gilbert

St. Mary Abbots Church

Kensington Church St, Kensington, London W8 4LA, UK

On June 28, 1901, after a nearly three year engagement, Gilbert and Frances were married in St. Mary Abbots, a beautiful Gothic Anglican church. It was a Catholic church until the English Reformation, but after the Church of England took it over, many famous Englishmen have been parishioners there, including Isaac Newton, Beatrix Potter, William Thackeray, and William Wilberforce. In more recent times, former UK Prime Minister David Cameron worshipped there, as did Princess Diana.

It was moving to pray at the spot of their wedding, trying to picture Gilbert and Frances standing in the sanctuary, staring into each others' eyes, vowing to love each other until death.

GKC and Frances' First Home

1 Edwardes Square, London, W8 6HE

(NOTE: the address is now 3 Earls Terrace, London, W8 6HE)

After Gilbert and Frances were married, they moved to 1 Edwardes Square, a small home just around the corner from 11 Warwick Gardens, were Gilbert grew up. They lived there from 1901 until (roughly) 1903. His close friend E.C. Bentley wrote of the home:

[Gilbert] lived in a quaint little house in Edwardes Square for a year or two after his marriage, when his name was not in standing so high as it is now. I remember the house well, with its garden of old trees and its general air of Georgian peace. I rememebr, too, the splendid flaming frescoes, done in vivid crayons, of knights and heroes and divinities, with which G.K.C. embellished the outside wall at the back, beneath a sheltering portico. I have often wondered whether the landlord charged for them as dilapidations at the end of his tenancy.

Fleet Street

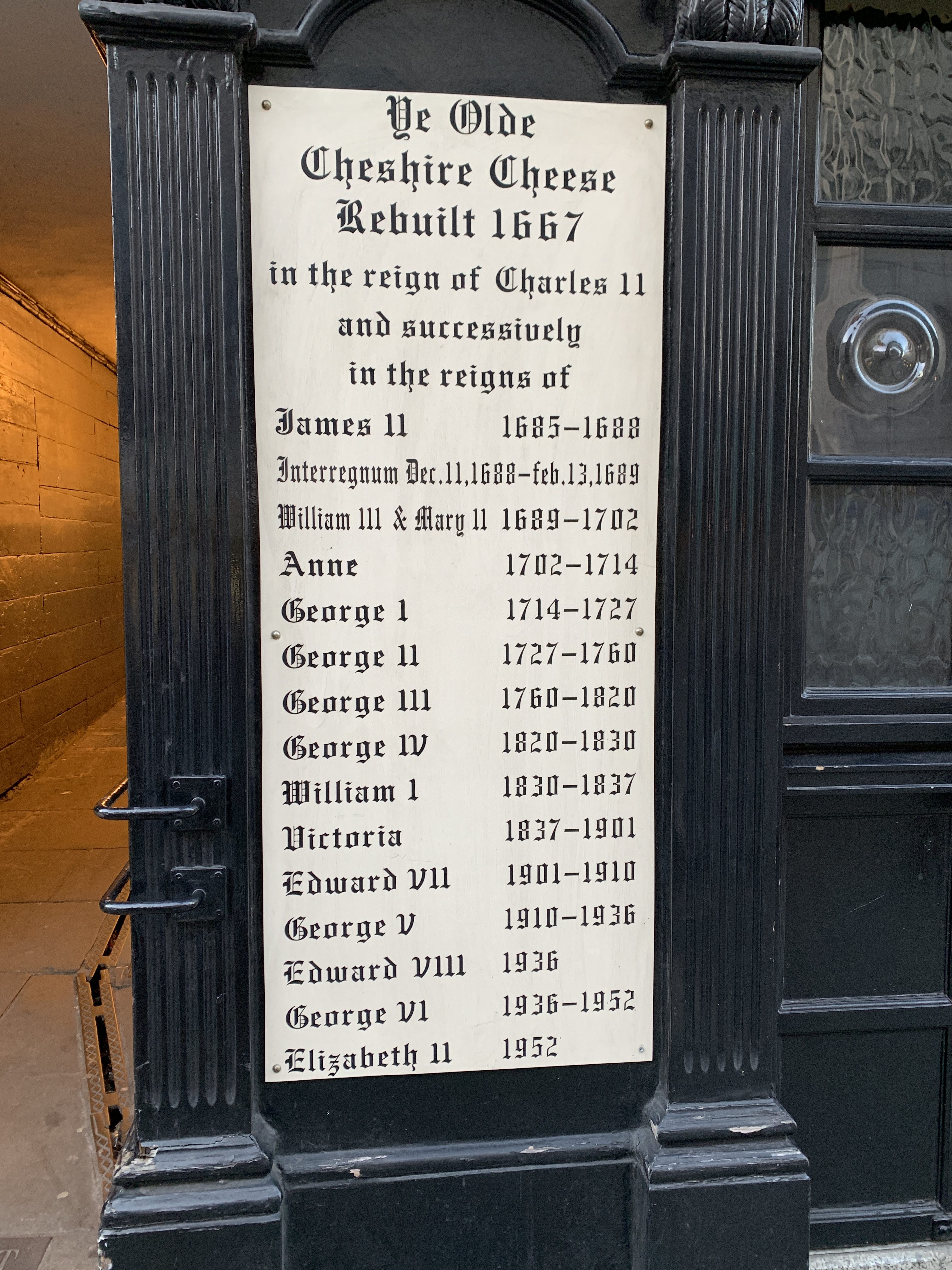

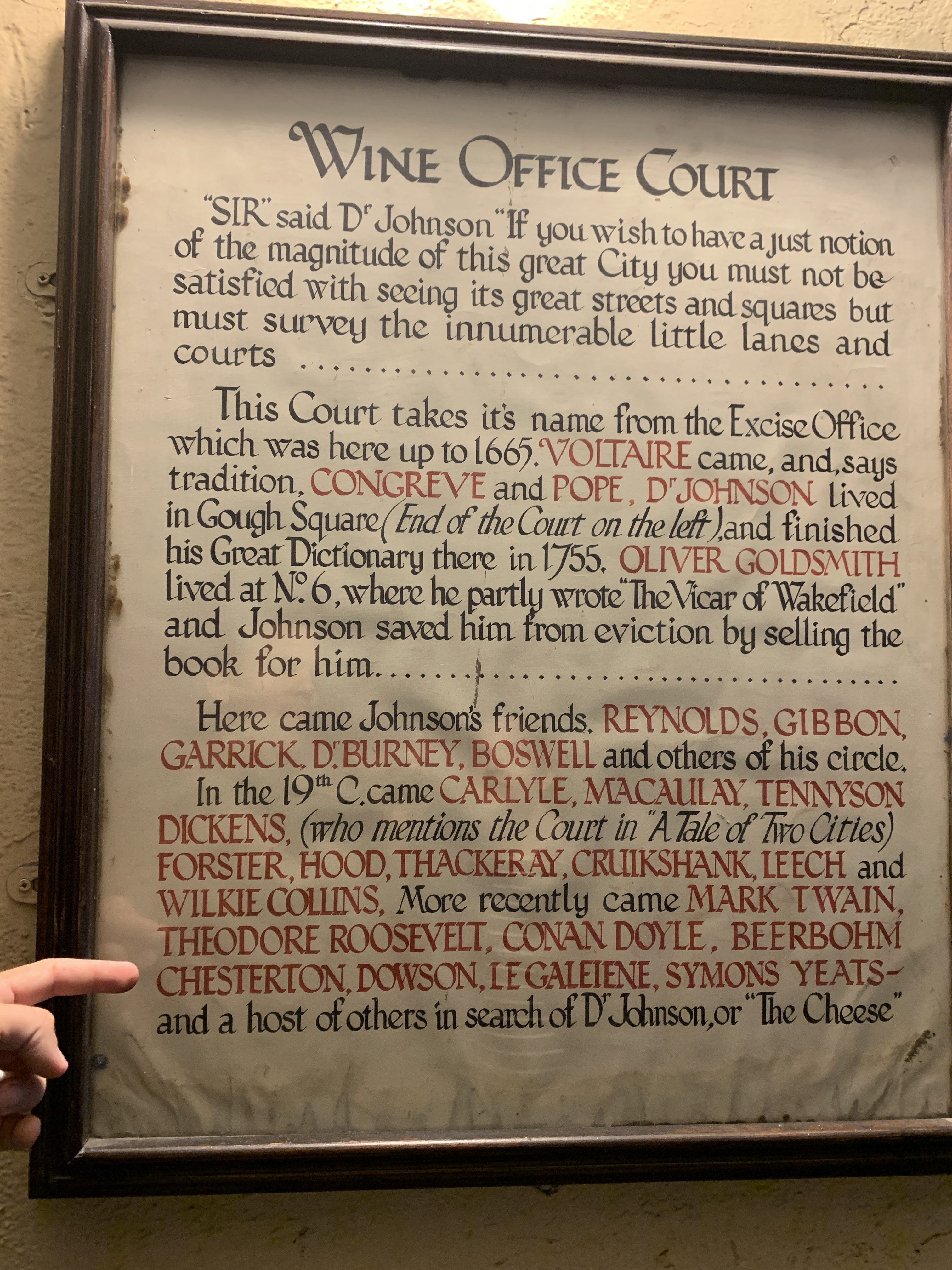

Ye Old Cheshire Cheese Pub

145 Fleet St, London EC4A 2BU, UK

Chesterton frequented many pubs in London. He especially liked the Fleet Street pubs, which hosted the city's top writers, poets, and artists. Ye Old Chesire Cheese was among the more popular stops, and Chesterton was a regular there.

The current building dates back to 1667 and has been visited by Samuel Johnson, Charles Dickens, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and, of course, Chesterton. Nearly every major English literary figure of the last three hundred years has imbibed there.

Former Offices of G.K.'s Weekly

22 Little Essex St, Temple, London, WC2R 3LD, UK

Gilbert's younger brother, Cecil, ran a weekly newspaper before leaving to fight in World War I, and after Cecil's death in the war, Gilbert resolved to take over the reins. The newspaper changed names a couple times before landing on G.K.’s Weekly, and this is where they had their offices.

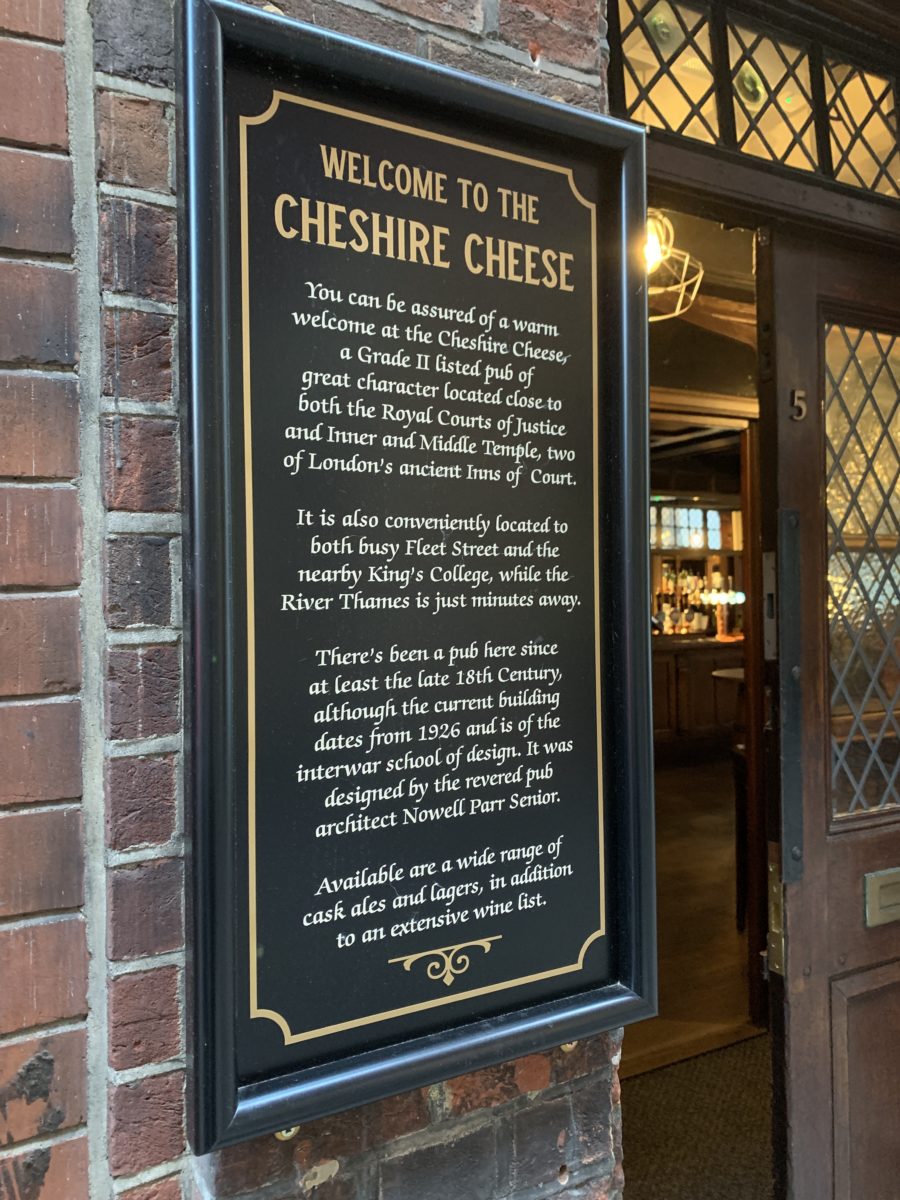

The Cheshire Cheese Pub

5 Little Essex St, Temple, London WC2R 3LD, UK

Not to be confused with Ye Olde Chesire Cheese (above), this pub is just across the street from the former G.K’s Weekly offices and is where Chesterton did a lot of his writing from 1925-1936. One can imagine him hunched over a table, scribbling out a new article, sipping a pint every few paragraphs and laughing at his own wit.

St. Paul’s Cathedral

St. Paul's Churchyard, London EC4M 8AD, UK

This large, domed Anglican church looks like a mini-St. Peter’s Basilica and can be seen from all over London.

Chesterton knew this church well, and visited many times. It was the setting for his novel, The Ball and Cross, named after the ball and cross atop the church’s dome.

The church was unfortunately closed when we arrived late at night, so we couldn’t go in.

Beaconsfield

NOTE: Beaconsfield is the town most associated with the Chestertons. By car, it's about 45 minutes west of London, halfway between London and Oxford, but we took the train from London. Once you arrive at the Beaconsfield train station, the spot of Chesterton's conversion to Catholicism, you can walk to and from all the sites below—a car isn't necessary.

After getting married, Gilbert and Frances Chesterton decided that London wasn't where they wanted to put down roots. They were both drawn to the country, and eventually moved to the small, rural village of Beaconsfield in 1909, staying there for the rest of their lives.

However, the choice of Beaconsfield was almost by accident, as Gilbert explains in his Autobiography:

My wife and I lived for about a year in Kensington, the place of my childhood; but I think we both knew that it was not to be the real place for our abode. I remember that we strolled out one day, for a sort of second honeymoon, and went upon a journey into the void, a voyage deliberately objectless.

I saw a passing omnibus labelled “Hanwell” and, feeling this to be an appropriate omen [Hanwell was the local lunatic asylum in Chesterton's time], we boarded it and left it somewhere in a stray station, which I entered and asked the man in the ticket-office where the next train went to. He uttered a pedantic reply: “Where do you want to go to?” And I uttered the profound and philosophical rejoinder, “Wherever the next train goes to.” It seemed that it went to Slough; which may seem to be singular taste, even in a train.

However, we went to Slough, and from there set out walking with even less notion of where we were going. And in that fashion we passed through the large and quiet cross-roads of a sort of village, and stayed at an inn called The White Hart. We asked the name of the place and were told that it was called Beaconsfield (I mean of course that it was called [pronounced] Beconsfield and not Beaconsfield), and we said to each other, “This is the sort of place where some day we will make our home.”

When the Chestertons moved to Beaconsfield in 1909, there wasn't much there, just a small town center and a handful of country homes. Today, it’s become one of the wealthiest suburbs of London, with a “new town” to complement the “old town.”

During our visit, as my wife and I walked past the chic fashion stores and coffee shops, I joked to her that maybe one day we could move there, perhaps into the Chesterton's own home! But then we saw the prices. A peek into the window of a real estate office revealed homes for sale. We were stunned to see that a small, two-bedroom house in Beaconsfield goes for around £750,000 (nearly $1,000,000 in U.S. dollars.)

Speaking of real estate, Gilbert’s father owned a prominent real estate company that is still around today, and still visible throughout England. The name “Chesterton” appears all over the place in both London and Beaconsfield.

The White Hart

The White Hart, Aylesbury End, Beaconsfield HP9 1LW, UK

During the Chestertons' first visit to Beaconsfield, they stayed at The White Hart Inn, which offered both lodging and a pub. When they later moved to Beaconsfield, Gilbert frequented the pub. In fact, locals used to call it “G.K.’s” and for a while after his death they had a bust of Chesterton on display.

The White Hart still exists, though today it's merely a restaurant. My wife and I had lunch there with our good friend Stephen Bullivant and his family.

Across the street from The White Hart is The Royal Saracen’s Head, another pub, immortalized in Chesterton’s book The Flying Inn.

Next to The Royal Saracen’s Head stands a World War I monument that Chesterton refers to in his Autobiography. He helped underwrite the cost of its construction, although there was controversy over his choice of a crucifix instead of a plain cross. Residents worried the crucifix was too Catholic.

Overroads (Chestertons' House #1)

2 Grove Rd, Beaconsfield HP9 1UR, UK

The Chestertons' first home in Beaconsfield was Overroads, where they lived from 1909-1922. Unfortunately, there’s no historic plaque on the house, and it’s privately owned, which means there's not much to see. You can only walk up to the gated entryway—no further.

After the Chestertons died, the house was left to the local Catholic diocese, which sold it to private owners. Interestingly, the current owner is trying to sell the house again, with an asking price of £1.9 million pounds (about $2.4 million U.S. dollars). They're not having much luck and, sadly, they’ve hinted that if they’re unable to find a buyer, they will sell it to a developer who will then demolish it to build new flats (i.e., apartments). Unlike the Chestertons’ other home in Beaconsfield, Top Meadow, which has been recognized as a historical site, Overroads has no such protections keeping it from being destroyed. If only the diocese had never sold the house!

Top Meadow (Chestertons' House #2)

1 Grove Rd, Beaconsfield HP9 1UR, UK

While living at Overroads, the Chestertons built a studio directly across the street for Gilbert to do his writing work. They soon expanded the studio into a full house, which became Top Meadow, their second and final home in Beaconsfield.

(Confusingly, Overroads is addressed #2 Grove Road and Top Meadow is #1 Grove Road, despite Overroads being constructed first.)

In 1922, the Chestertons moved from Overroads to Top Meadow, where Gilbert and Frances lived until their deaths in 1936 and 1938, respectively. The house also includes a side building known as Top Meadow Cottage, which served as a residence for the Chestertons’ longtime secretary and surrogate daughter, Dorothy Collins.

In their will, the Chestertons left both Beaconsfield houses (Overroads and Top Meadow) to the local Catholic diocese, requesting that the property be used as a seminary, a convent, or as transition houses for Anglican priests who had converted to Catholicism. The diocese honored that request, and for a while several convert-priests did in fact live at Top Meadow. But eventually, as noted above, the diocese sold both properties and they remain privately owned today, which is a shame because it means Chesterton pilgrims are unable to tour inside or around either house. As with Overroads, the closest you can get is the gate in front of the property. Thankfully, you can still read the blue plaque over the door, which reads “G.K. Chesterton Lived Here 1922-36”.

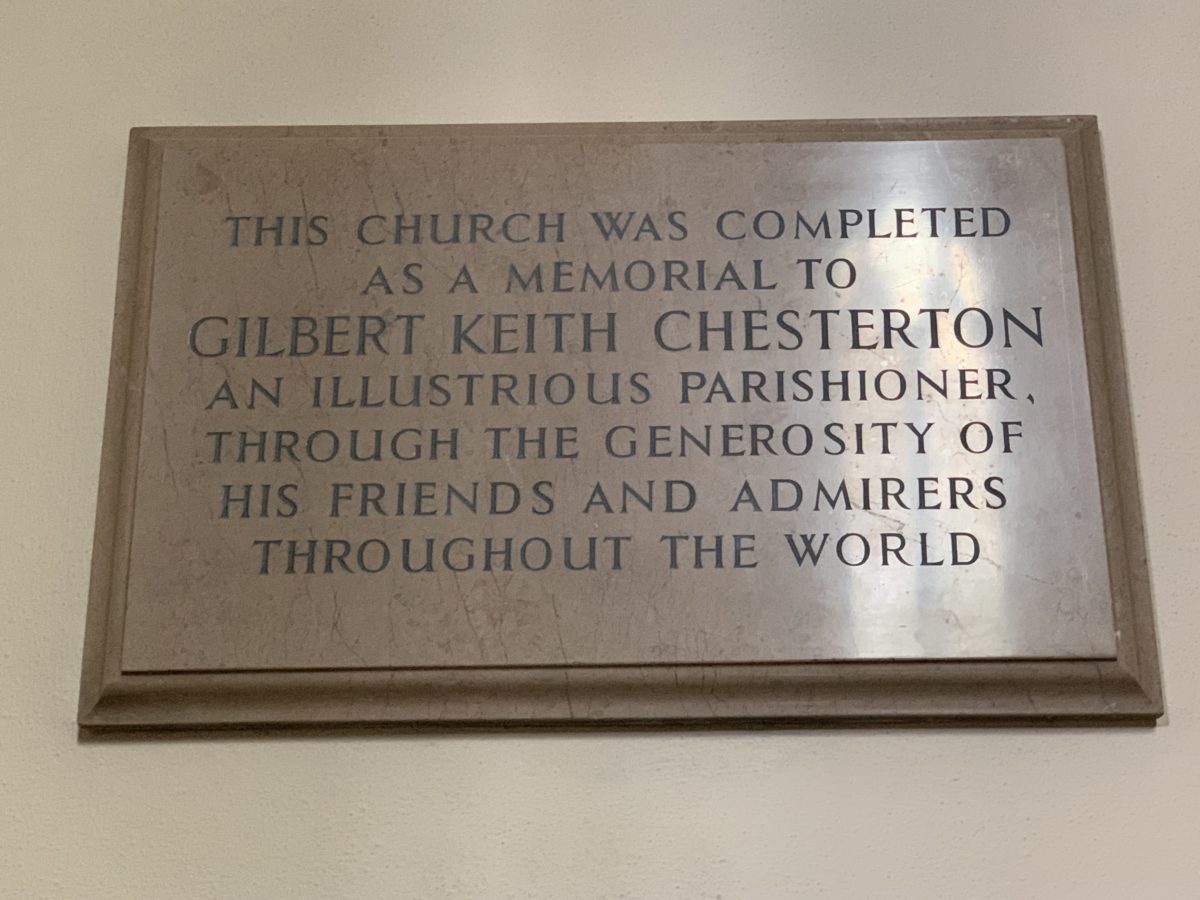

St. Teresa’s Catholic Church

40 Warwick Rd, Beaconsfield HP9 2PL, UK

When the Chestertons first moved to Beaconsfield in 1909, there was no Catholic Church. That wasn't a huge problem for them since neither Gilbert nor Frances were Catholic at that point. However, even after their conversion, it was a while before they had a church. Local Catholics were forced to meet for Mass in the backroom of a hotel near the railway stop.

It wasn’t until 1926 that the community raised enough funds to build their first Catholic parish. Chesterton, one of the main contributors, wanted the parish to be named after the English martyrs, and was disappointed to learn it would be named “St. Teresa’s,” after St. Thérèse of Lisieux. (St. Thérèse was canonized the same year the Church was built.) Chesterton wasn’t fond of St. Thérèse at the time, though near the end of his life, he made a pilgrimage to Lisieux and seems to have warmed to her.

(For an excellent study of Chesterton and Thérèse, and the childhood faith they shared, read Fr. John Saward's book, The Way of the Lamb: The Spirit of Childhood and the End of the Age. It's out of print but you can find used copies online.)

St. Teresa’s Church is a small, but beautiful Gothic space with simple decor and stone work. You can see Chesterton’s influence throughout the church. For example, sitting on a pedestal to the right of the altar is a beguiling statue of Mary, donated by Gilbert himself. He talks about the statue in his book, Christendom in Dublin, and one can imagine him sitting in the pew each week, gazing into those determined eyes.

I heard a story in Ireland years ago about how someone had met in the rocky wastes a beautiful peasant woman carrying a child. And on being asked for her name she answered simply: “I am the Mother of God, and this is Himself, and He is the boy you will all be wanting at the last.” I have never forgotten this phrase, and I remembered it suddenly long afterwards.

I was looking about for an image of Our Lady which I wished to give to the new church in our neighbourhood, and I was shown a variety of very beautiful and often costly examples in one of the most famous and fashionable Catholic shops in London… But somehow I felt fastidious, for the first time in my life; and felt that the one kind was too conventional to be sincere and the other too primitive to be popular… and I ended prosaically by following the proprietor to an upper floor, where there was a sort of lumber room, full of packages and things partially unpacked, and it seemed suddenly that she was standing there, amid planks and shavings and sawdust, as she stood in the carpenter’s shop in Nazareth. I said something, and the proprietor answered rather casually: “Oh, that’s only just been unpacked; I’ve hardly looked at it. It’s from Ireland!”

She was a peasant and she was a queen. She was barefoot like any colleen on the hills; yet there was nothing merely local about her simplicity. I have never known who was the artist and I doubt if anybody knows; I only know that it is Irish, and I almost think that I should have known without being told. I know a man who walks miles out of his way at regular intervals to revisit our church where the image stands. She looks across the little church with an intense earnestness in which there is something of endless youth; and I have sometimes started, as if I had actually heard the words spoken across that emptiness: “I am the Mother of God and this is Himself, and He is the boy you will all be wanting at the last.”

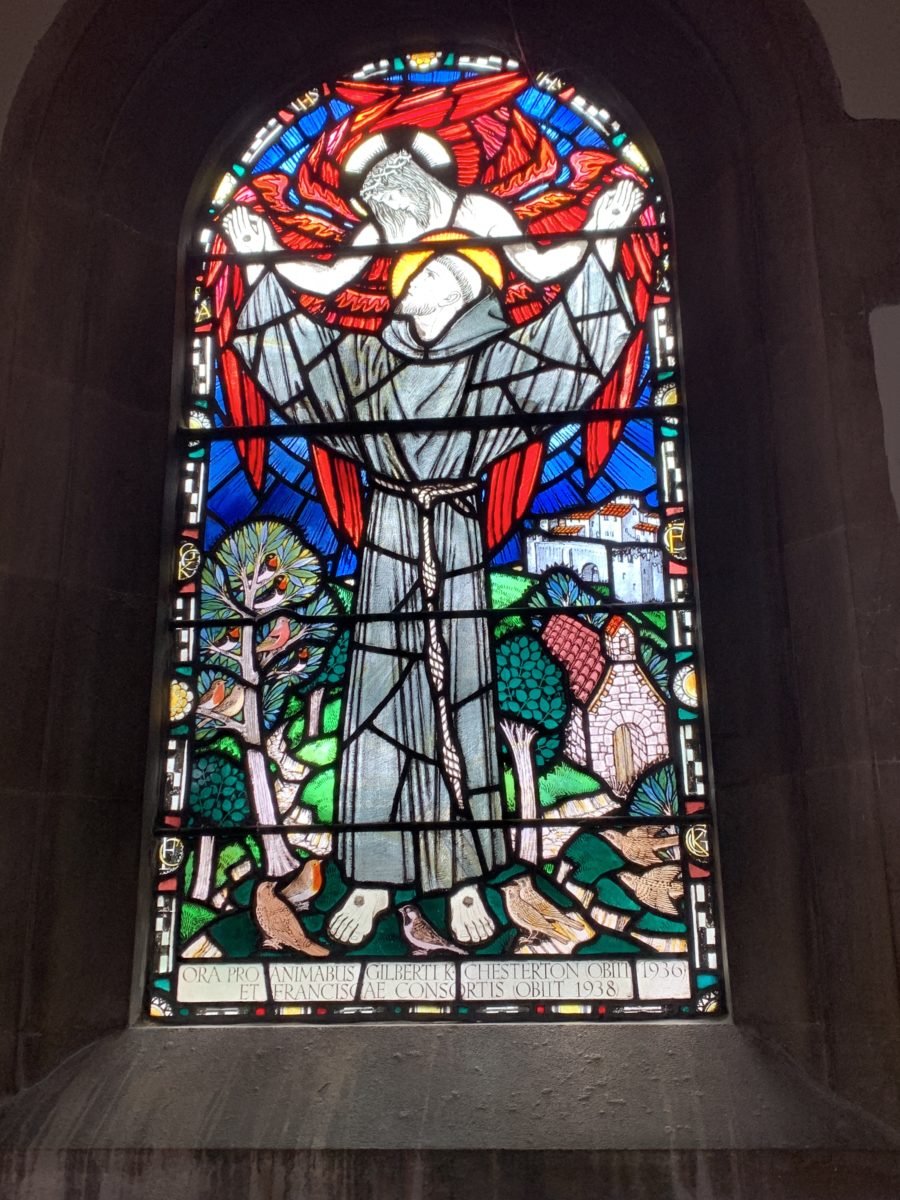

St. Teresa’s also has a window dedicated to the Chestertons, with an image of St. Francis, whom Chesterton profiled in his lauded biography.

St. Francis window in St. Teresa's Church in Beaconsfield, in memory of Gilbert and Frances Chesterton

There’s also a plaque dedicated to the Chestertons’ memory, added by parishioners during the church’s expansion (the church is now about twice as long as it was in Chesterton’s time.)

The new entryway to the parish boasts a beautiful stained glass window designed by an artist whose father was part of Eric Gill’s Distributist community in Ditchling. The window was inspired by a beautiful Chesterton poem titled "The Ballad of God-Makers", which is displayed next to the window.

In fact, speaking of Eric Gill, the acclaimed English sculptor, he designed the original tombstone for the Chestertons' grave. The one there now, in the cemetery, is a low-quality replica (more on that below). The original stone now hangs on an outside wall of St. Teresa’s parish.

Finally, at St. Teresa's there is a side altar dedicated to Sts. John Fisher and Thomas More. Its spiked gate and shackled wall rings call to mind the Tower of London. Though the chapel was completed after Chesterton died, it was built with funds Chesterton had left to the parish, and it seems to have fulfilled his wish for a church dedicated to the English martyrs.

In fact, in the tradition of many English Catholic parishes, the parish name was at some point expanded to include multiple saints. It’s now officially known as the “Catholic Church of St. Teresa of the Child Jesus and Saints John Fisher and Thomas More.”

During our visit, Kathleen and I got to celebrate Pentecost Mass at St. Teresa’s along with the Bullivants. The experience was so moving. It struck me, while praying after communion, that although we had already trekked across England on our pilgrimage, stopping at many Chesterton sites and touching many relics, searching for some profound connection with our dead hero, nowhere could we come into deeper contact with him than through the Blessed Sacrament. It’s through the Eucharist that the limits of time and space fade away, allowing us to reach across the expanse of death and commune with all those in the Mystical Body of Christ, including Gilbert and Frances Chesterton. Receiving communion in the very church where the Chestertons received communion each week—the very spot in that very church—and allowing Christ to bind us together, was a mystical experience I'll long cherish.

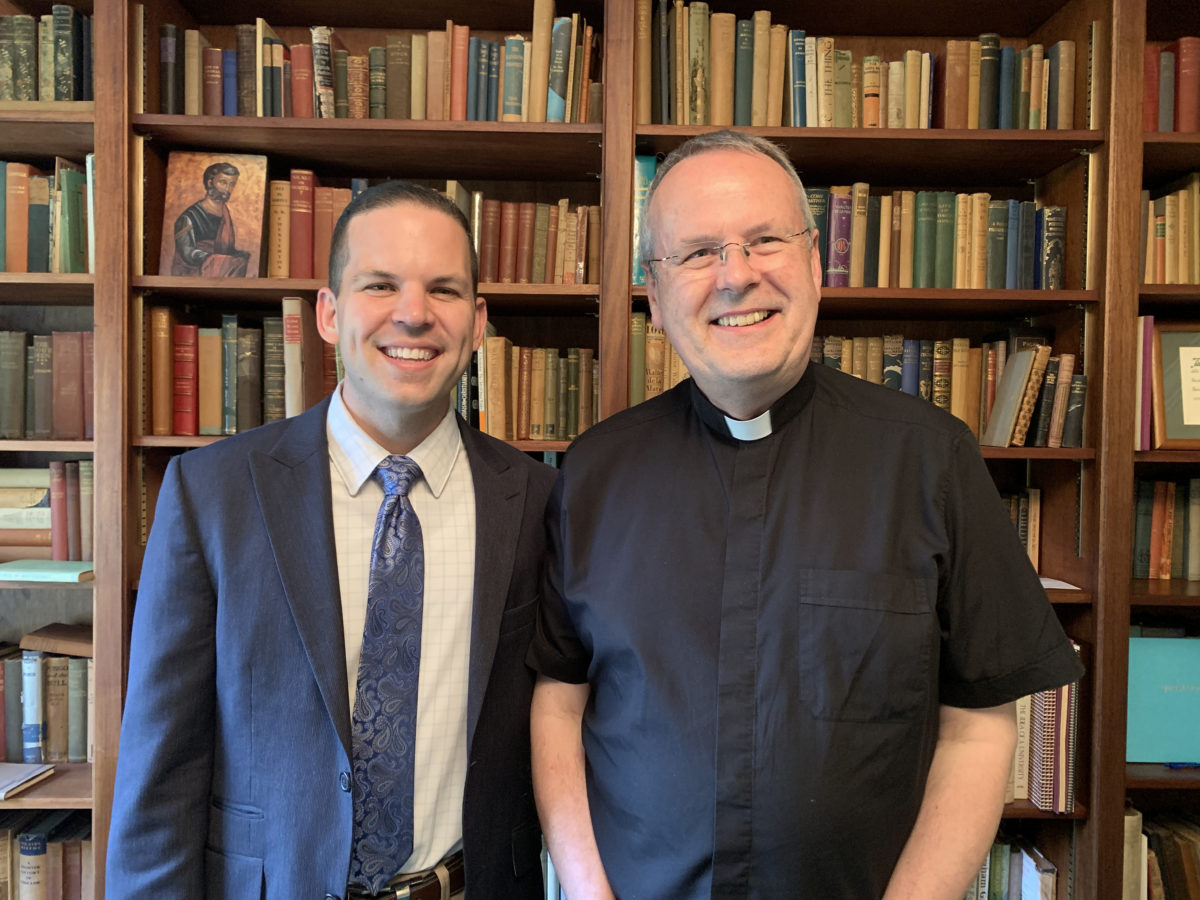

However, another huge treat awaited us after Mass. We met up with Canon John Udris, a friend and former pastor of St. Teresa's. He was the formal investigator for Chesterton's cause for canonization, which the local bishop decided not to pursue. Canon Udris and I became friends at a Chesterton conference in the United States, back in 2014.

With Canon John Udris, former pastor of St. Teresa's Catholic Church and investigator into the cause of canonization for G.K. Chesterton.

As the story goes, Canon Udris was assigned as pastor of St. Teresa’s knowing very little about Chesterton. But after moving in, he began reading up, getting to know him and falling in love with his writings.

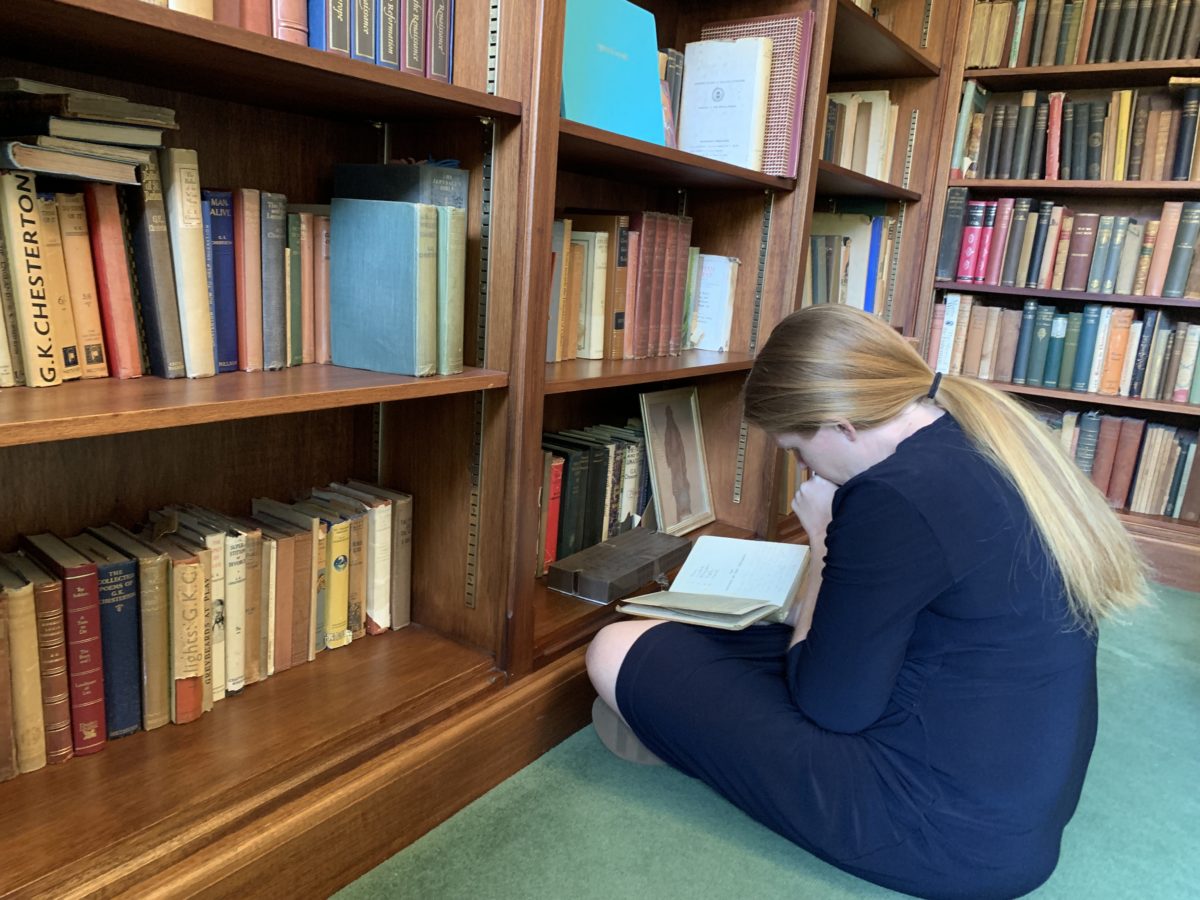

One day, he heard through the grapevine that the diocese was planning to sell Top Meadow Cottage to a private buyer. Canon Udris asked whether anyone had reviewed the contents of the house, or what they were planning to do with all of it. They answered, “Well, we’re hiring someone to just get rid of it.” Shocked and worried, he asked if he could possibly visit the house and poke through the items before the sale. They gave him permission, but said he had thirty six hours. Canon Udris quickly grabbed some boxes, zipped to the house, and scooped up everything he could find into his car. He didn’t have time to review the items—he just grabbed books, papers, files, whatever he could carry, and piled it all into boxes, shuttling it back to St. Teresa’s. He worked tirelessly for 36 hours and still wasn’t able to get everything.

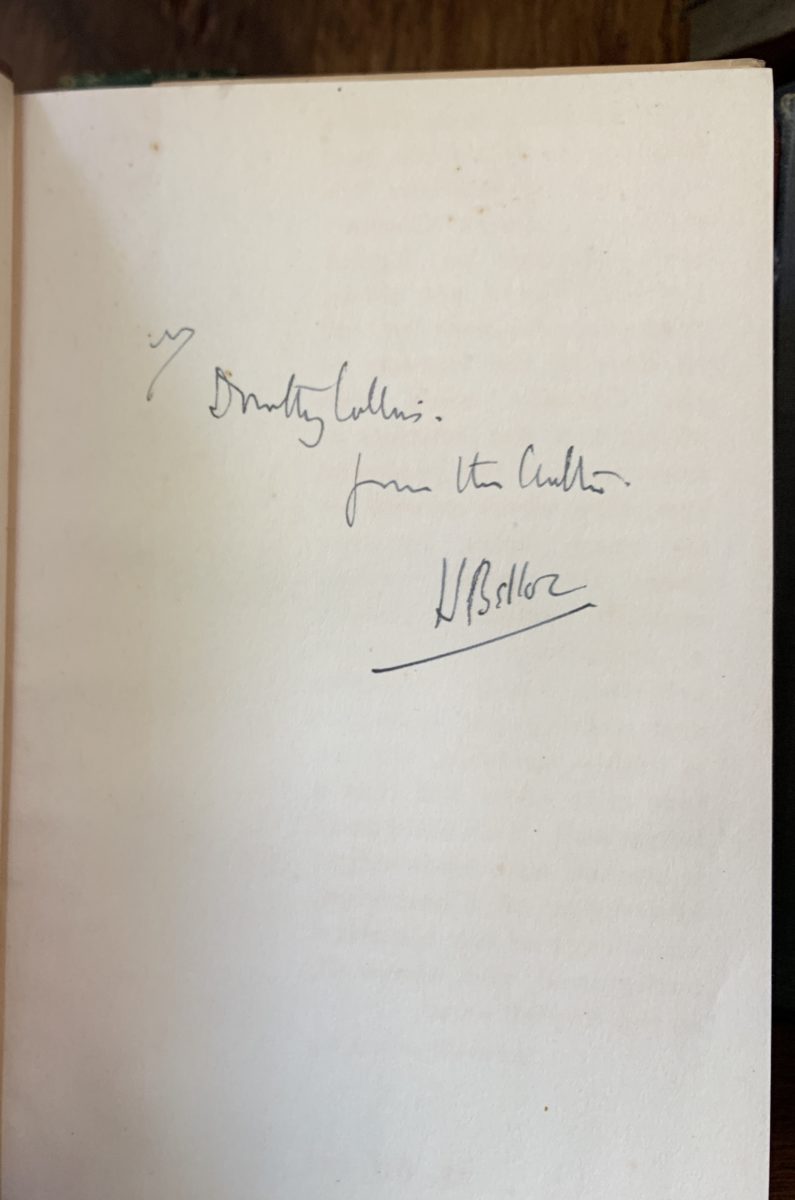

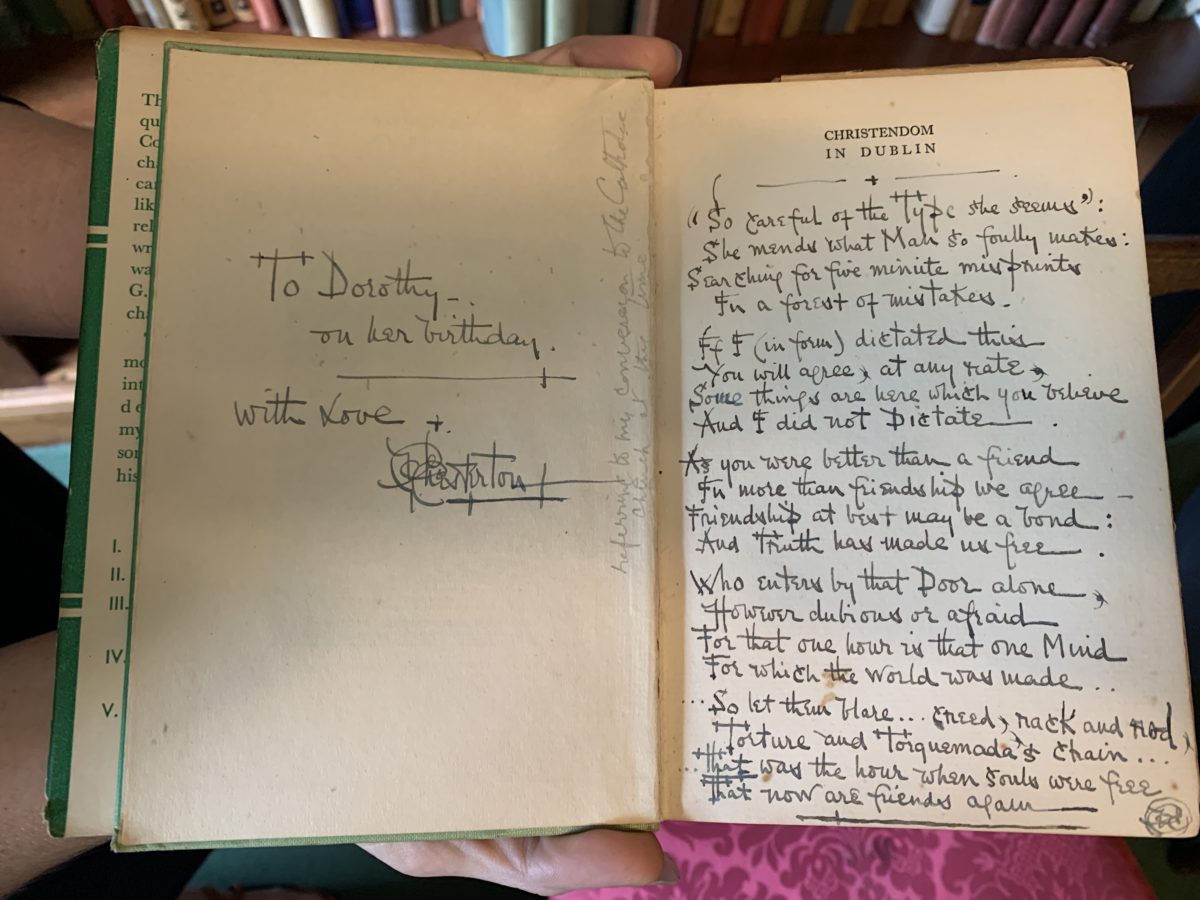

When he returned to St. Teresa’s, and finally had time to pour through the collection, he realized how remarkable it was. Virtually all of it belonged to Dorothy Collins, Gilbert's longtime secretary and literary executor. Canon Udris found stacks of letters sent to Dorothy after Gilbert's death, from people all over the world who knew Chesterton and wanted to share their memories. Most of the books in the collection belonged to Dorothy herself, and included first editions of nearly every Chesterton title. Each book was inscribed by Chesterton himself, to Dorothy, and typically not just with a signature but with a witty note or poem. Perhaps the most moving inscription, and Dorothy’s favorite according to Maise Ward’s Return to Chesterton, was the one inside Chesterton’s Christendom in Dublin, a poem celebrating Dorothy’s entrance into the Catholic Church.

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to his secretary, Dorothy Collins, in her copy of "Christendom in Dublin." Click to enlarge and read the poem.

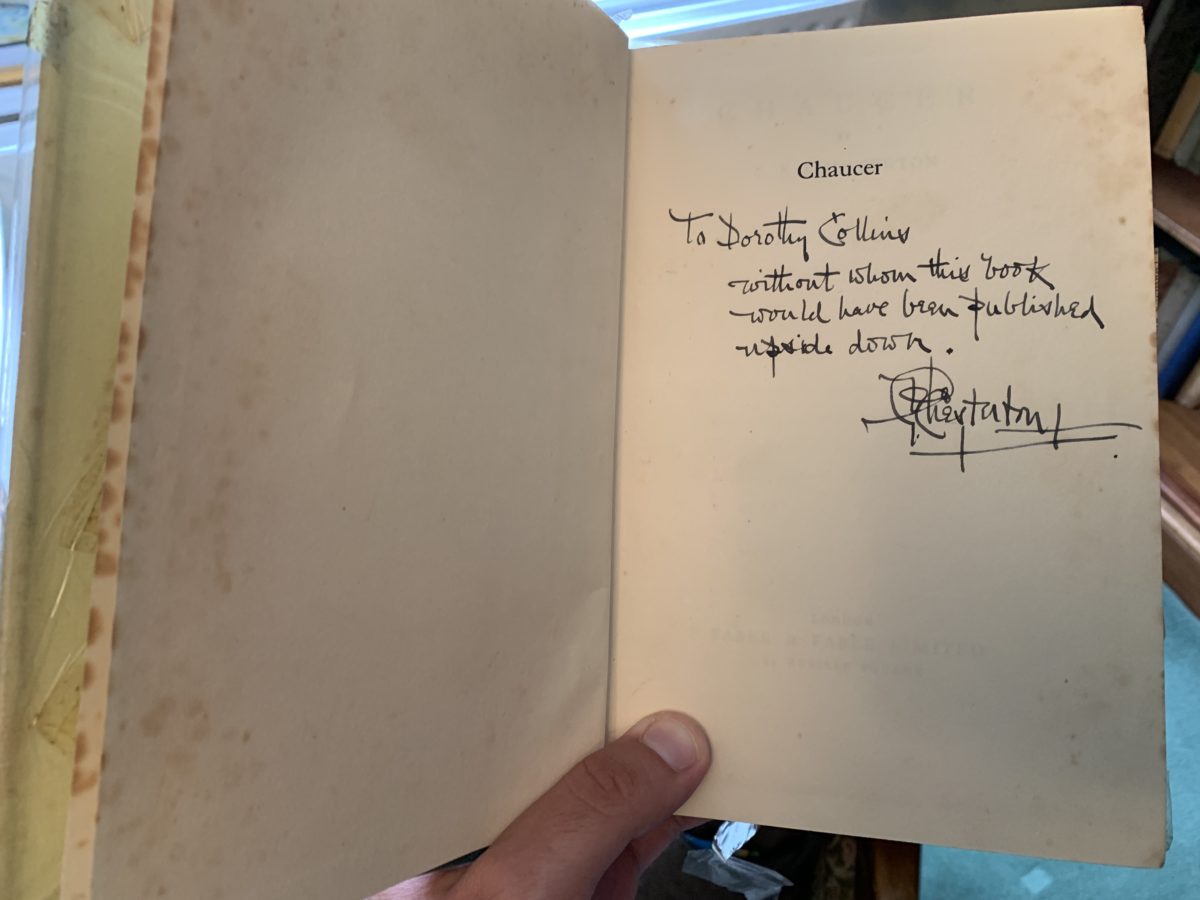

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to Dorothy Collins in his book "Chaucer." It says: "To Dorothy Collins, without whom this book would have been published upside down - G.K. Chesterton".

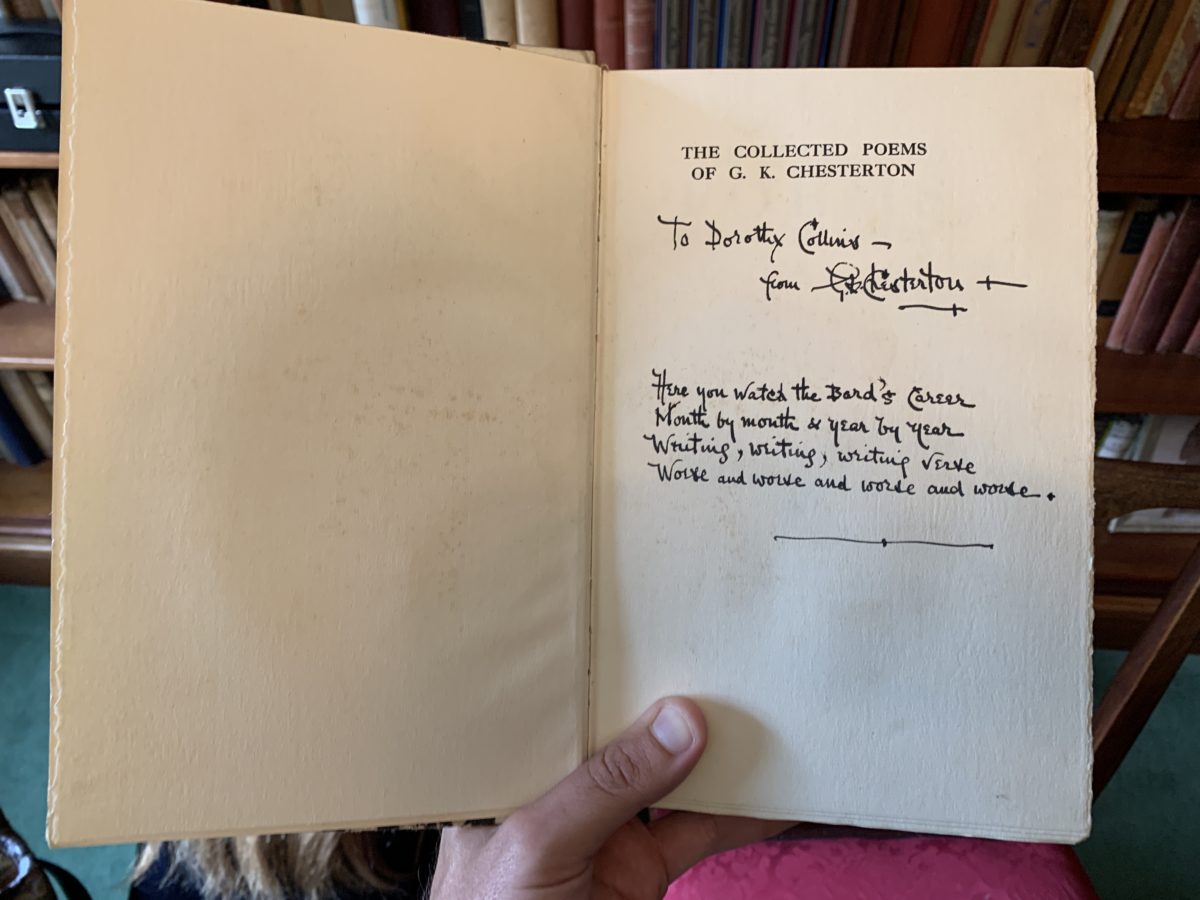

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to Dorothy Collins in his "Collected Poems of G.K. Chesteron." It says: "Here you watched the Bard's career, month by month and year by year // Writing, writing, writing verse, worse and worse and worse and worse."

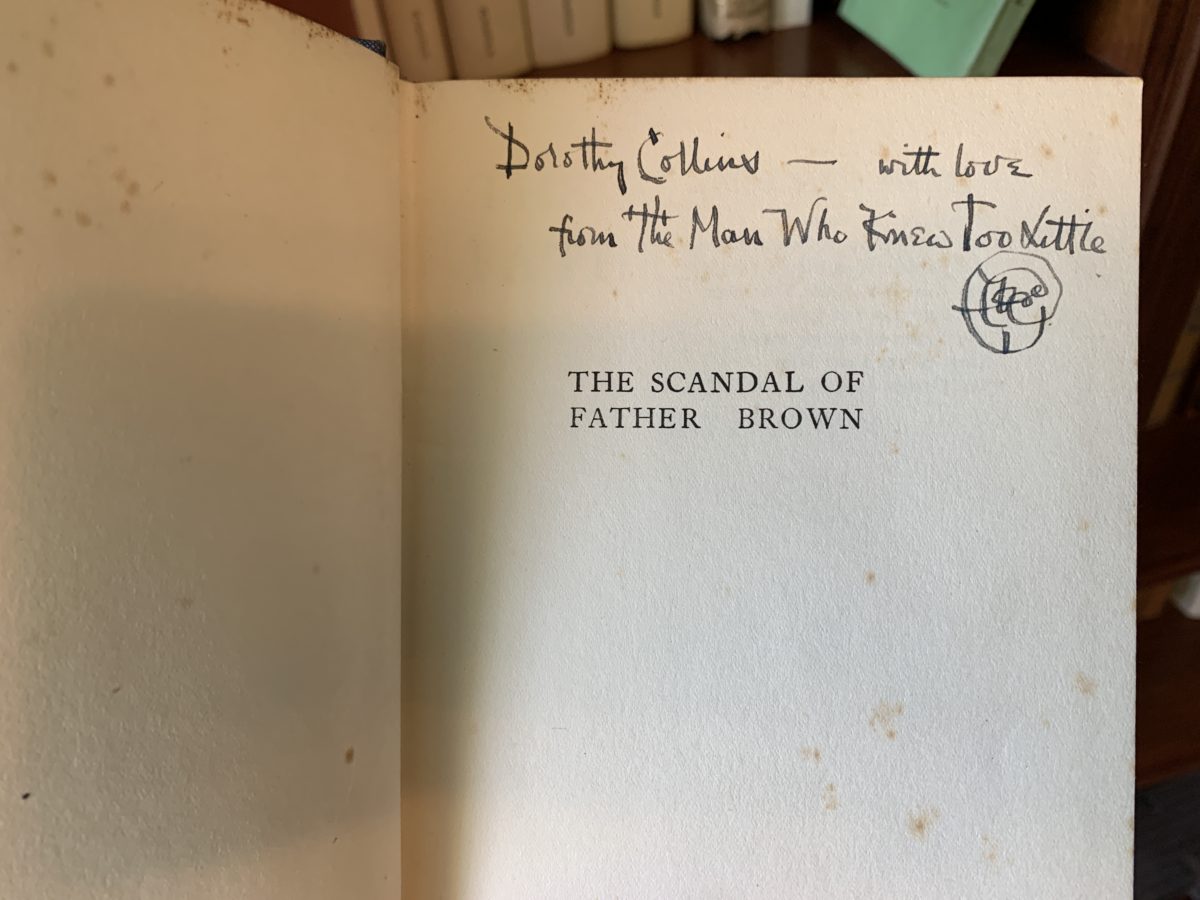

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to Dorothy Collins, in his book "The Scandal of Father Brown." It says: "Dorothy Collins -- with love from The Man Who Knew Too Little" (an obvious pun on Chesterton's book, The Man Who Knew Too Much)

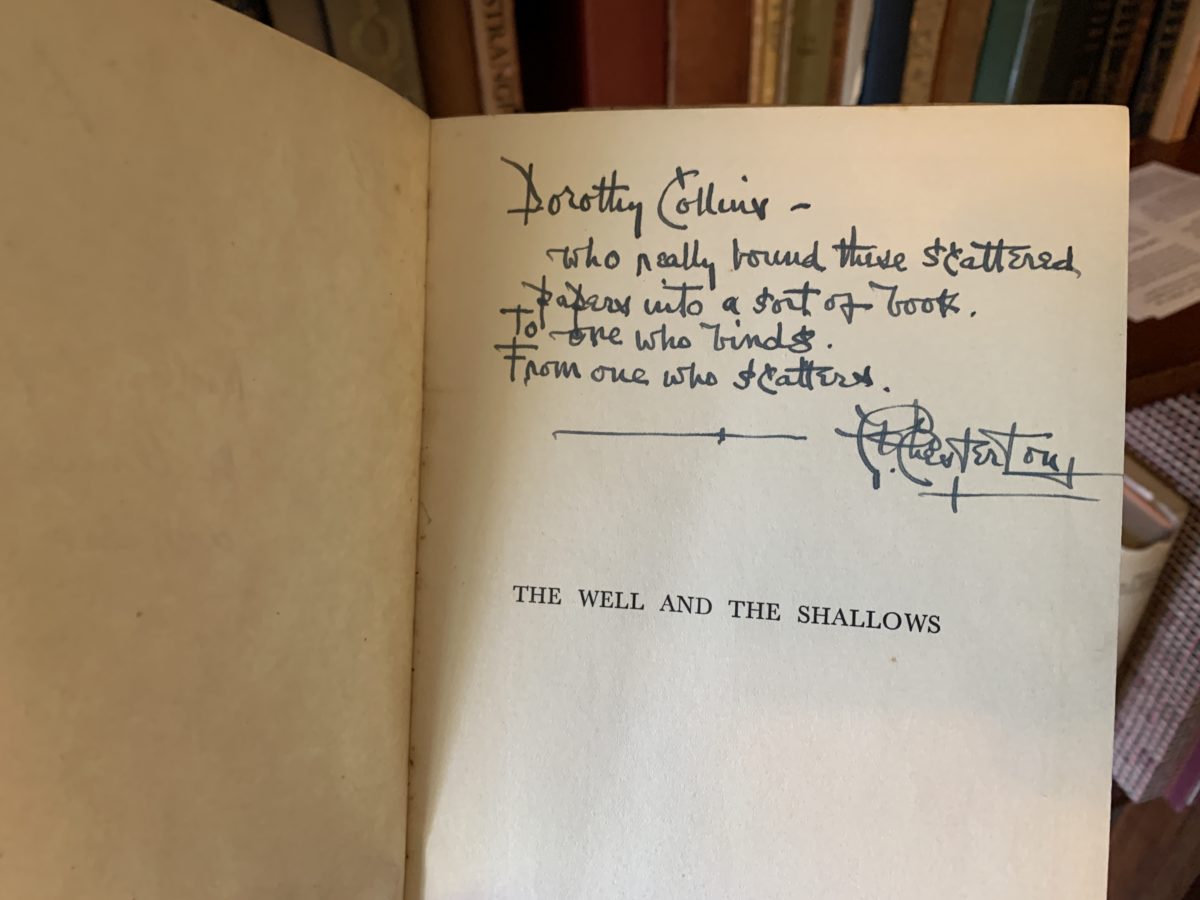

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to Dorothy Collins, in his book "The Well and the Shallows." The inscription says: "Dorothy Collins - who neatly bound these scattered papers into a sort of book. To one who binds, from one who scatters. - G.K. Chesterton".

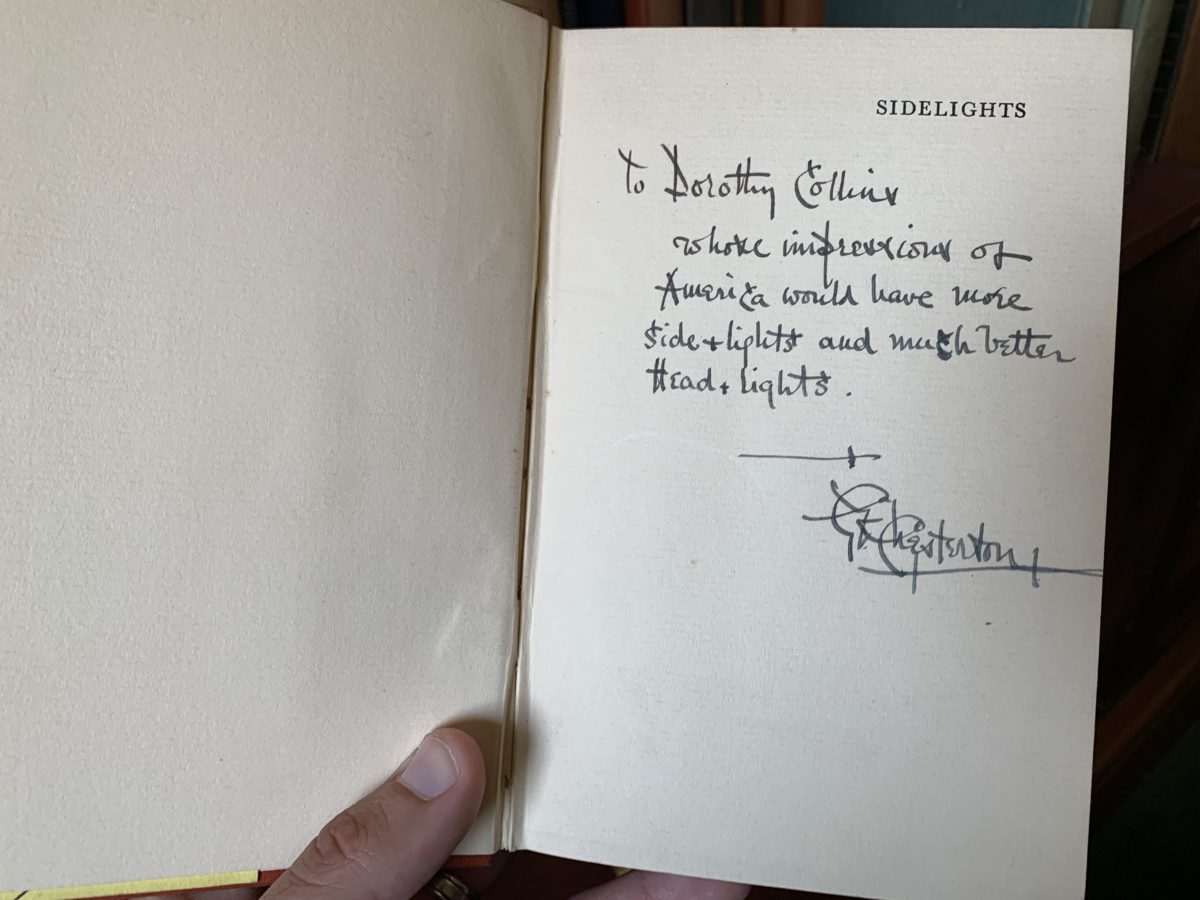

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to Dorothy Collins, in his book "Sidelights," which includes essays reflecting on his second visit to America. The inscription reads: "To Dorothy Collins, whose impressions of America would have more side+lights and much better head+lights."

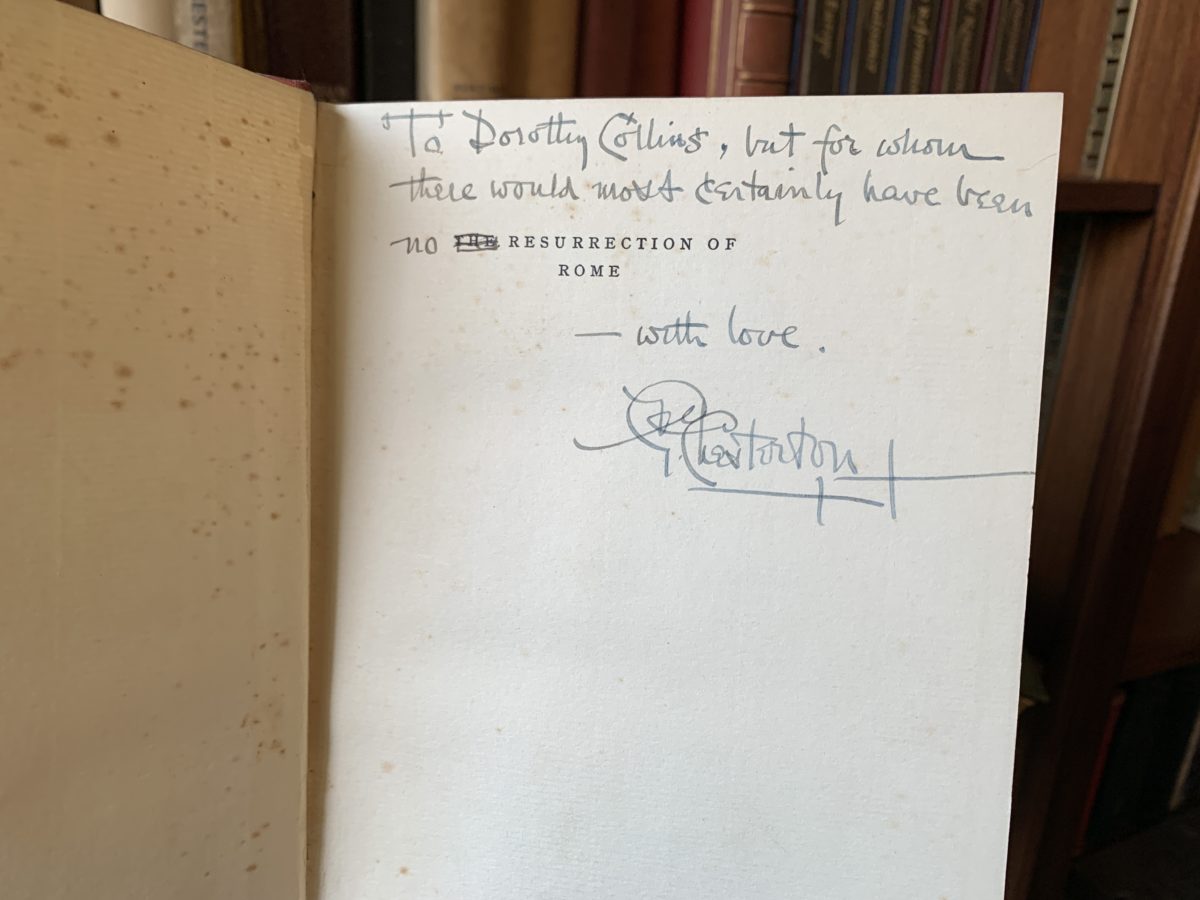

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to Dorothy Collins, in his book "The Resurrection of Rome." It reads: "To Dorothy Collins, but for whom there would most certainly have been The No Resurrection of Rome -- with love, G.K. Chesterton".

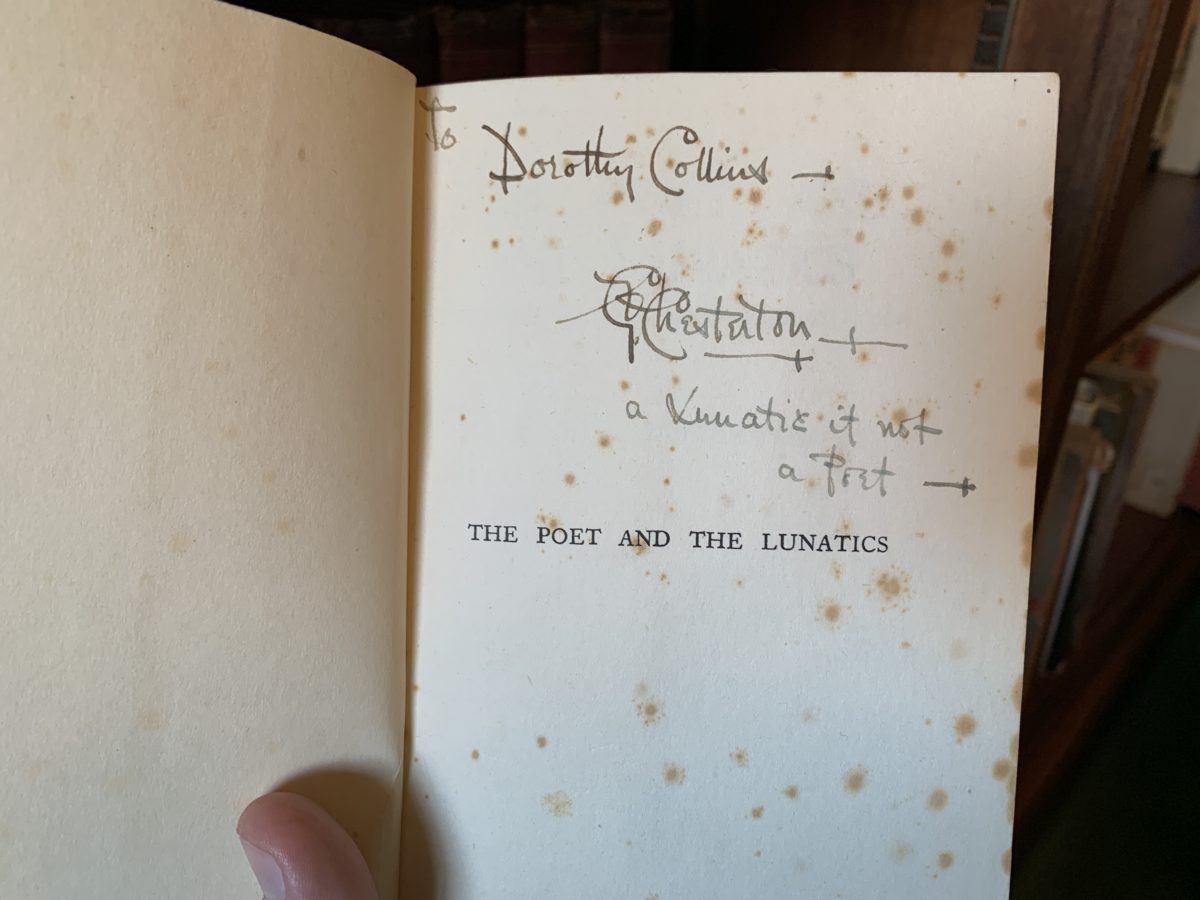

G.K. Chesterton's inscription to Dorothy Collins, in his book "The Poet and the Lunatics." It reads: "To Dorothy Collins - G.K. Chesterton - a Lunatic if not a Poet".

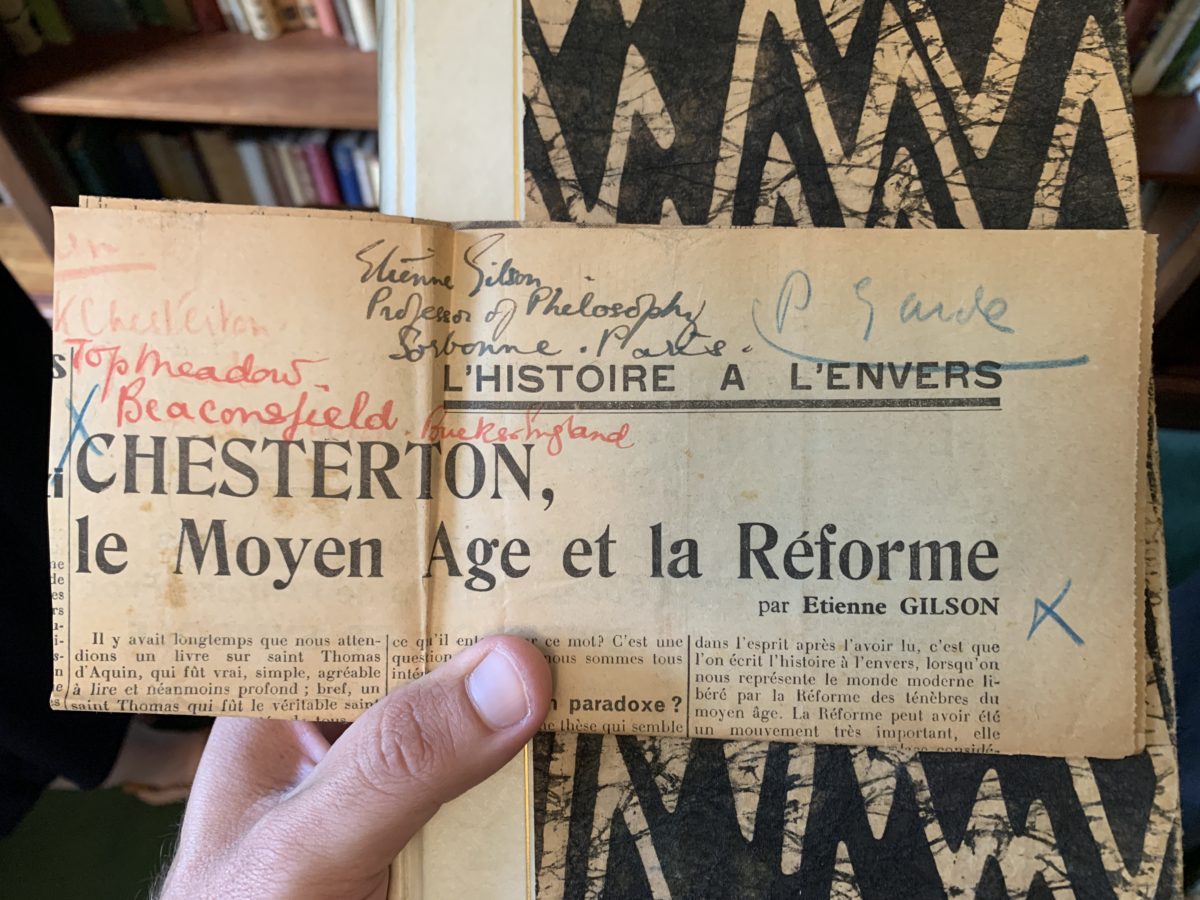

Dorothy kept reviews of each book, tucking them into the binding. For example, inside Chesterton’s book on St. Thomas Aquinas, she kept a clipping of the famous Etienne Gilson review in which the great Thomistic scholar says, in French:

I consider it as being without possible comparison the best book ever written on St. Thomas. Nothing short of genius can account for such an achievement.

Everybody will no doubt admit that it is a “clever” book, but the few readers who have spent twenty or thirty years in studying St. Thomas Aquinas, and who, perhaps, have themselves published two or three volumes on the subject, cannot fail to perceive that the so-called “wit” of Chesterton has put their scholarship to shame. He has guessed all that which they had tried to demonstrate, and he has said all that which they were more or less clumsily attempting to express in academic formulas.

Chesterton was one of the deepest thinkers who ever existed; he was deep because he was right; and he could not help being right; but he could not help being modest and charitable too, so he left it to those who could understand him to know that he was right, and deep; to the others, he apologized for being right, and he made up for being deep by being witty.

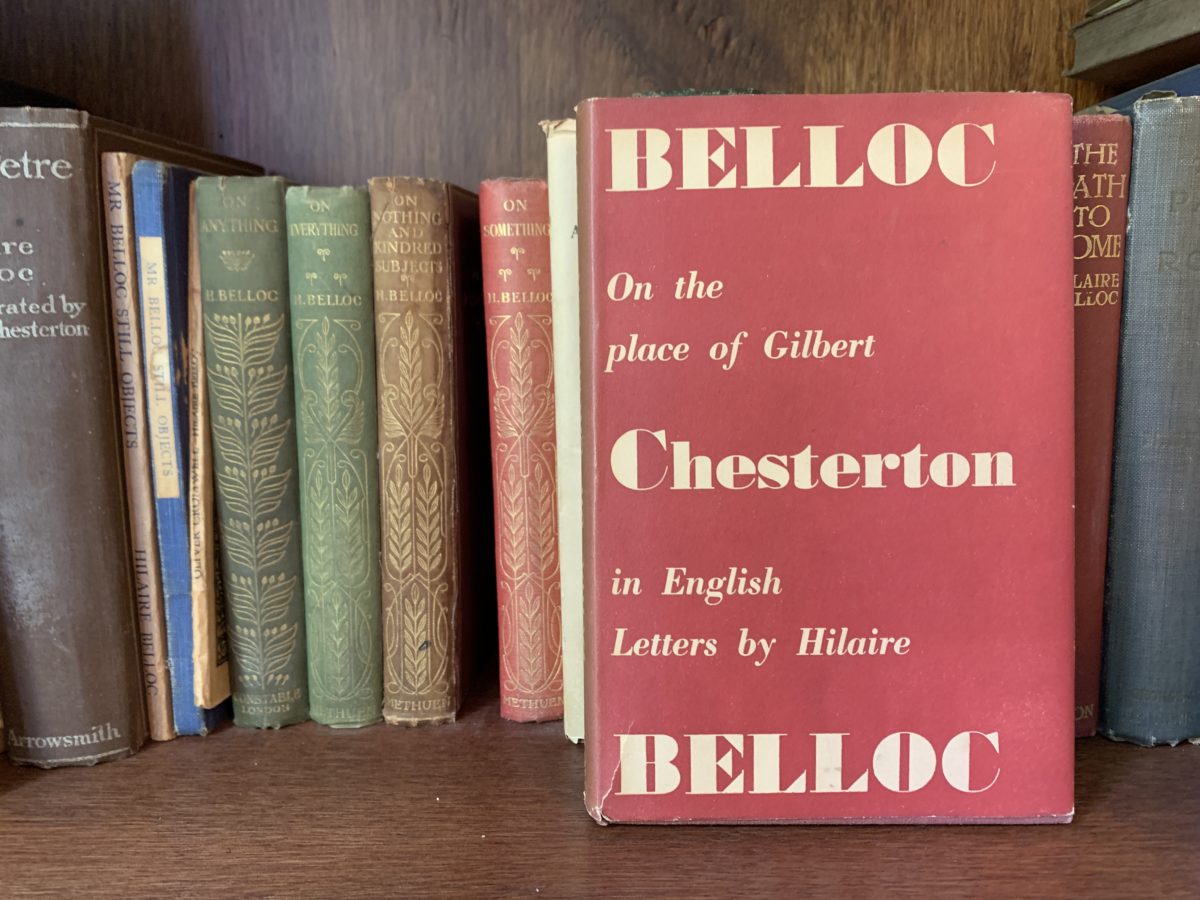

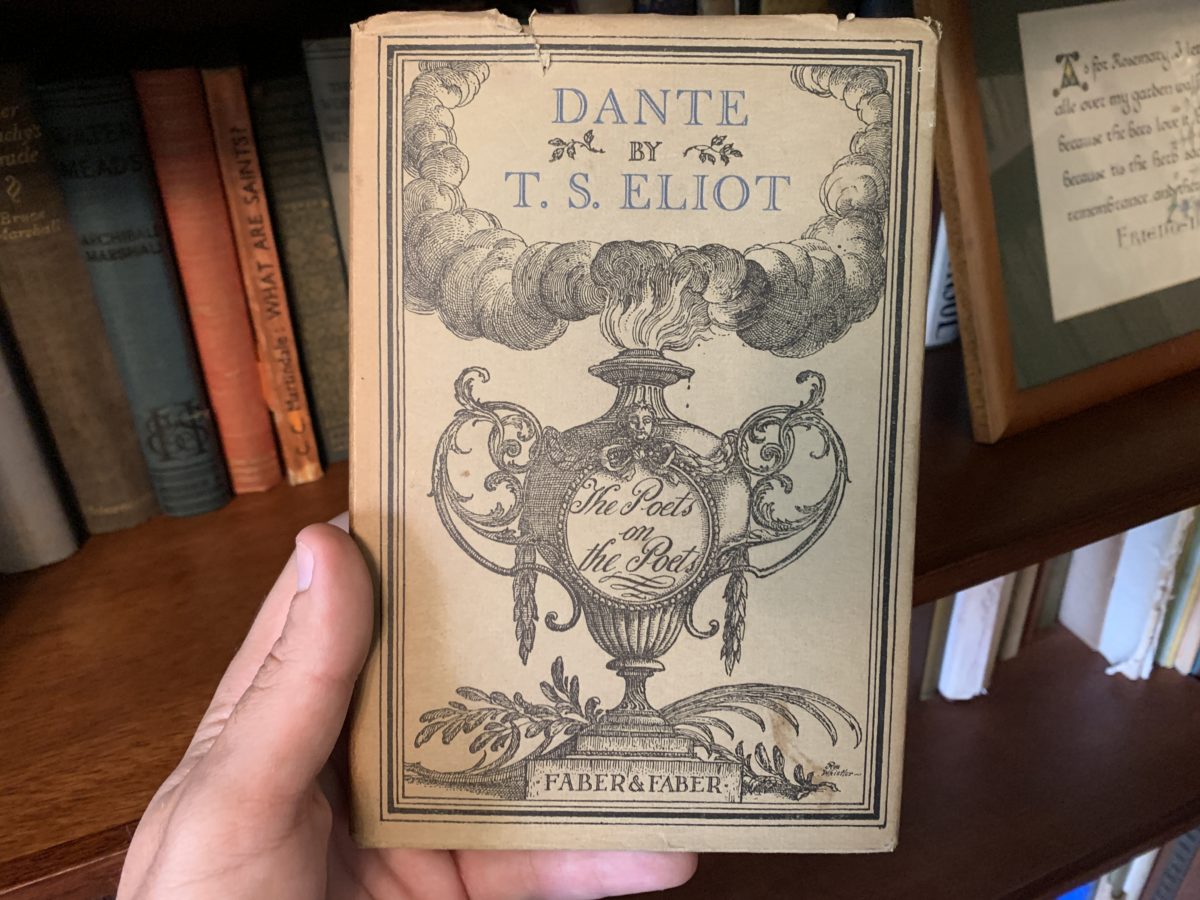

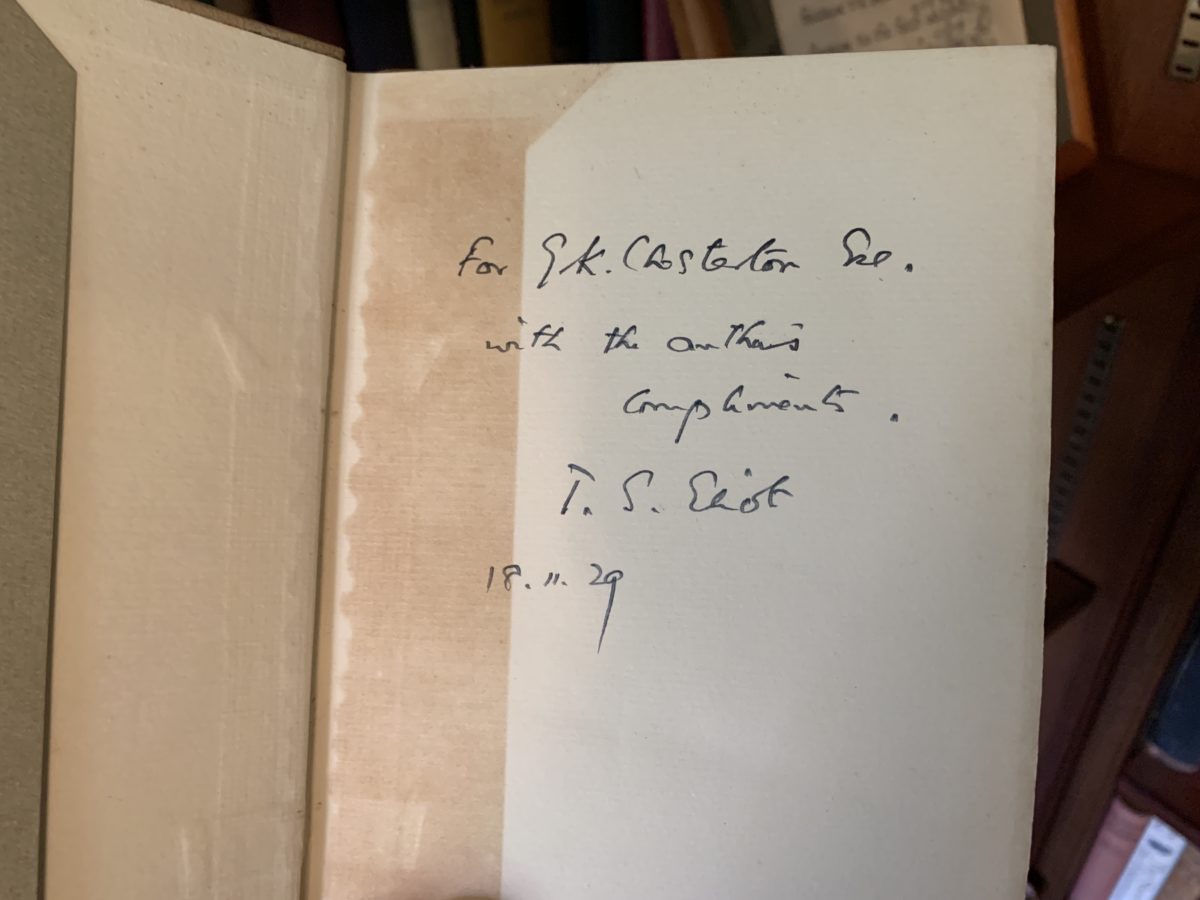

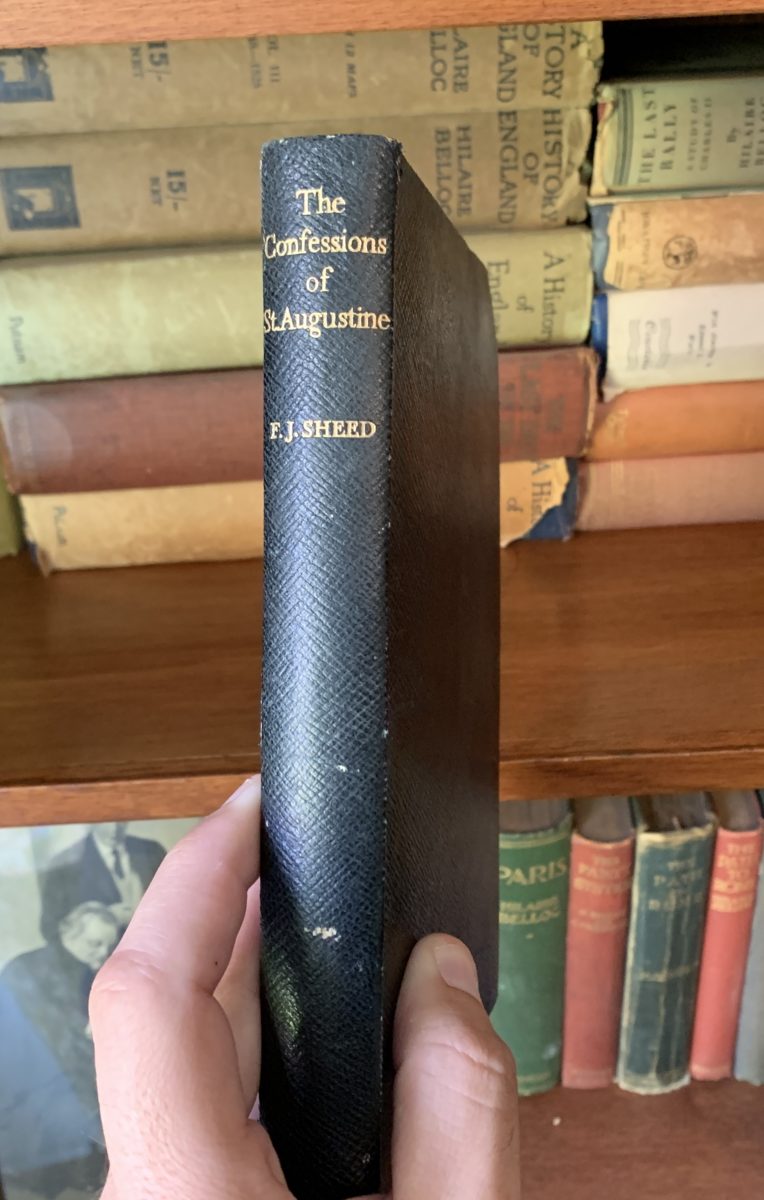

The collection also includes books that other famous authors sent to Gilbert and Dorothy, each with signatures and inscriptions, authors such as Hilaire Belloc, George Bernard Shaw, T.S. Eliot, H.G. Wells, Frank Sheed, and many more.

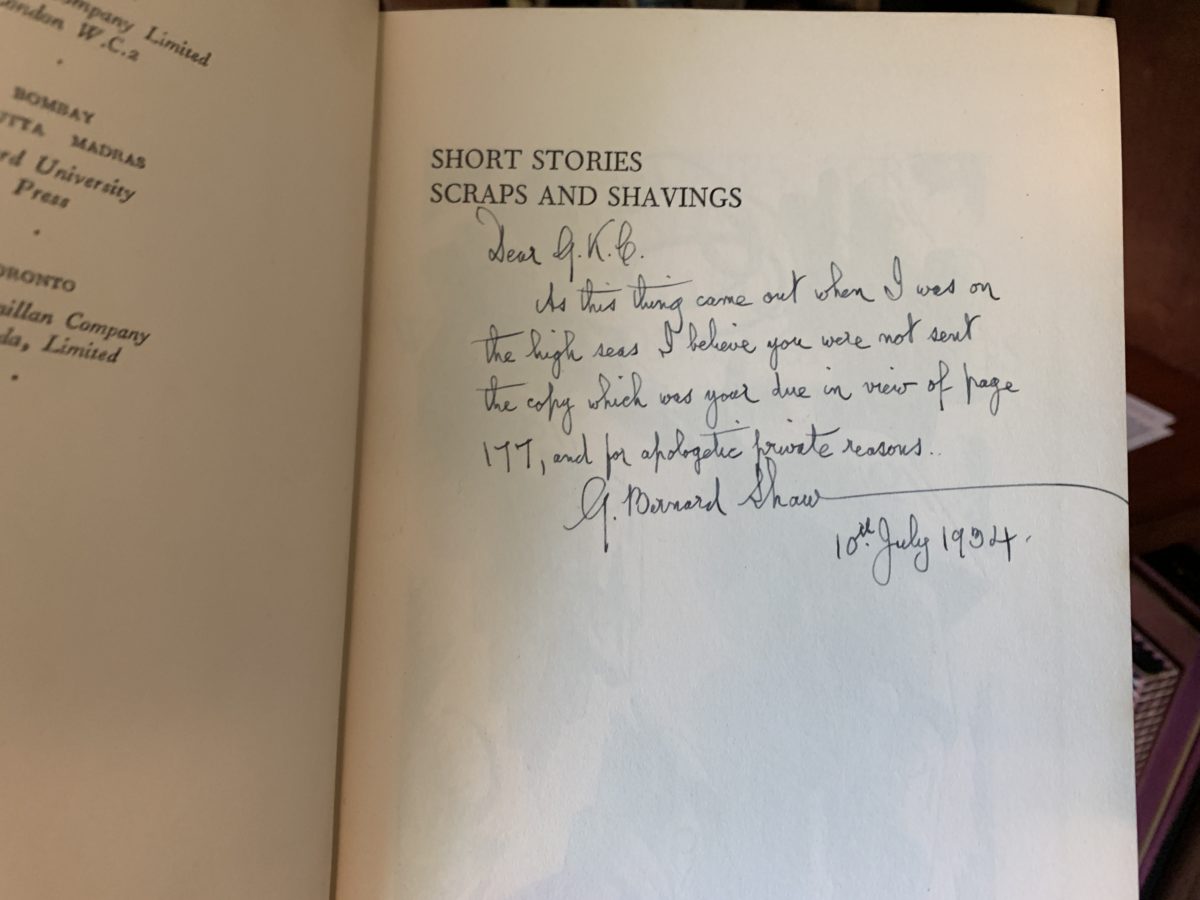

Inscription by George Bernard Shaw in a book titled "Short Stories, Scraps, and Shavings," which he gifted to Chesterton. Inscription reads: "Dear G.K.C., as this thing came out when I was on the high seas I believe you were not sent the copy which was your due in view of page 177, and for apologetic private reasons... - George Bernard Shaw".

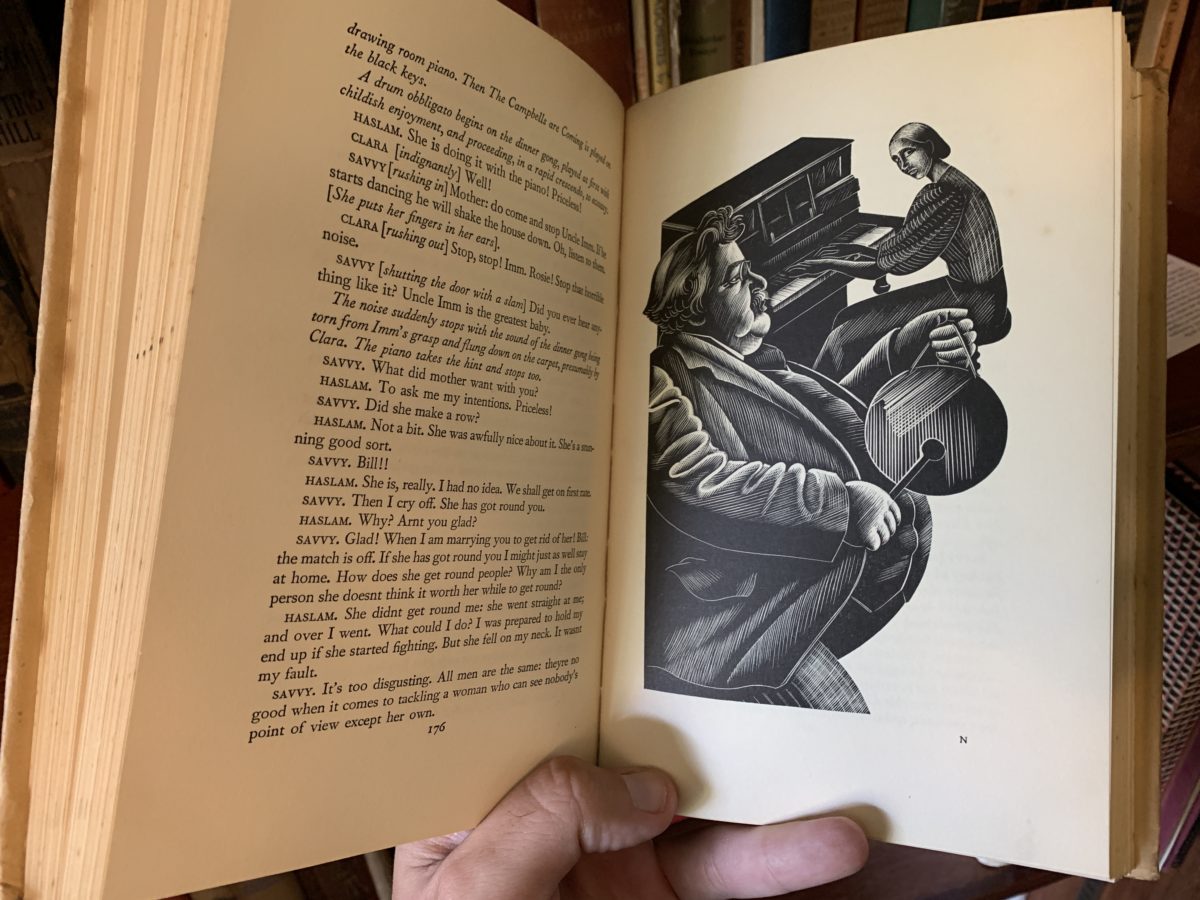

The aforementioned page 177 in Shaw's book, which features a fairly unflattering drawing of Chesterton banging a drum.

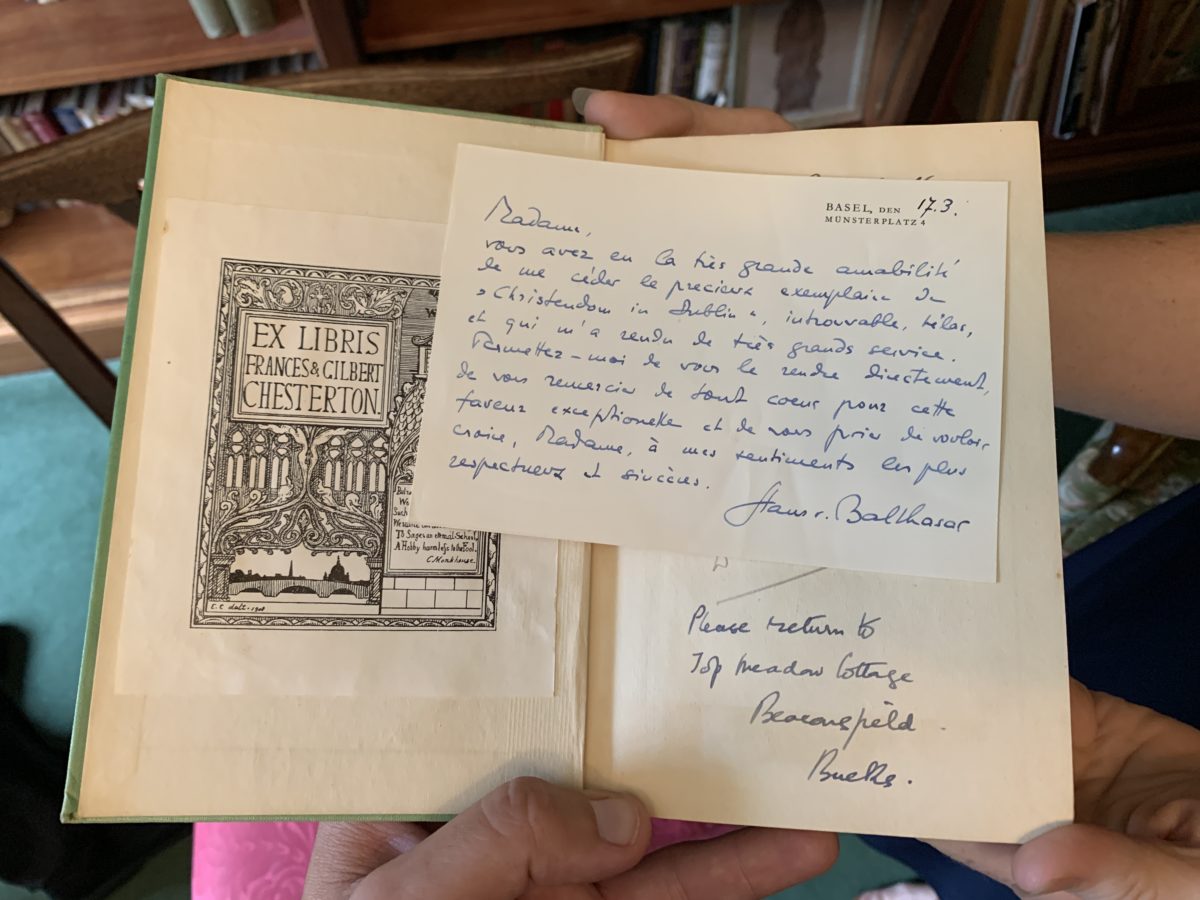

There’s even a handwritten letter from Hans Urs von Balthasar, thanking Dorothy for letting him borrow a copy of Chesterton’s Christendom in Dublin, which he previously requested and which Dorothy sent to him.

Hans Urs von Balthasar note to Dorothy Collins, thanking her for letting him borrow Chesterton's book, "Christendom in Dublin."

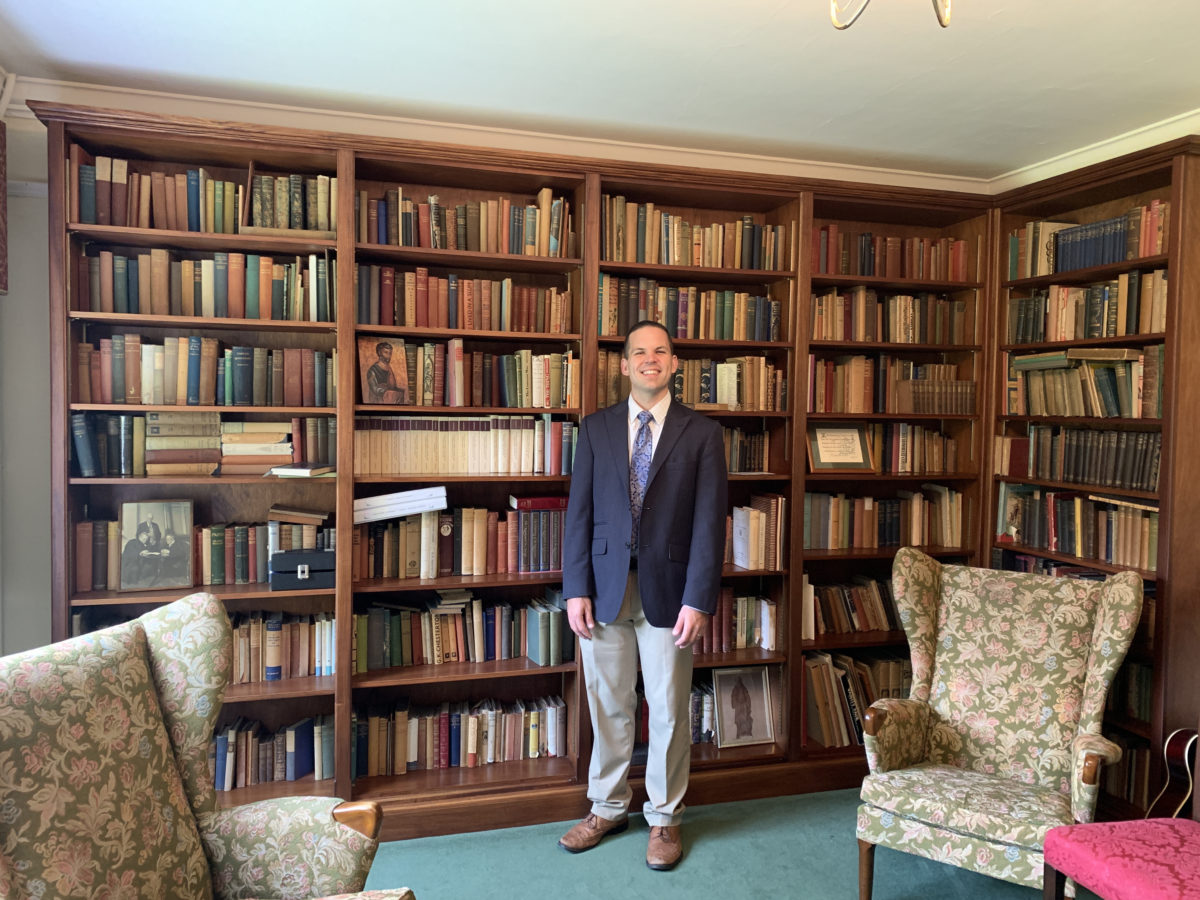

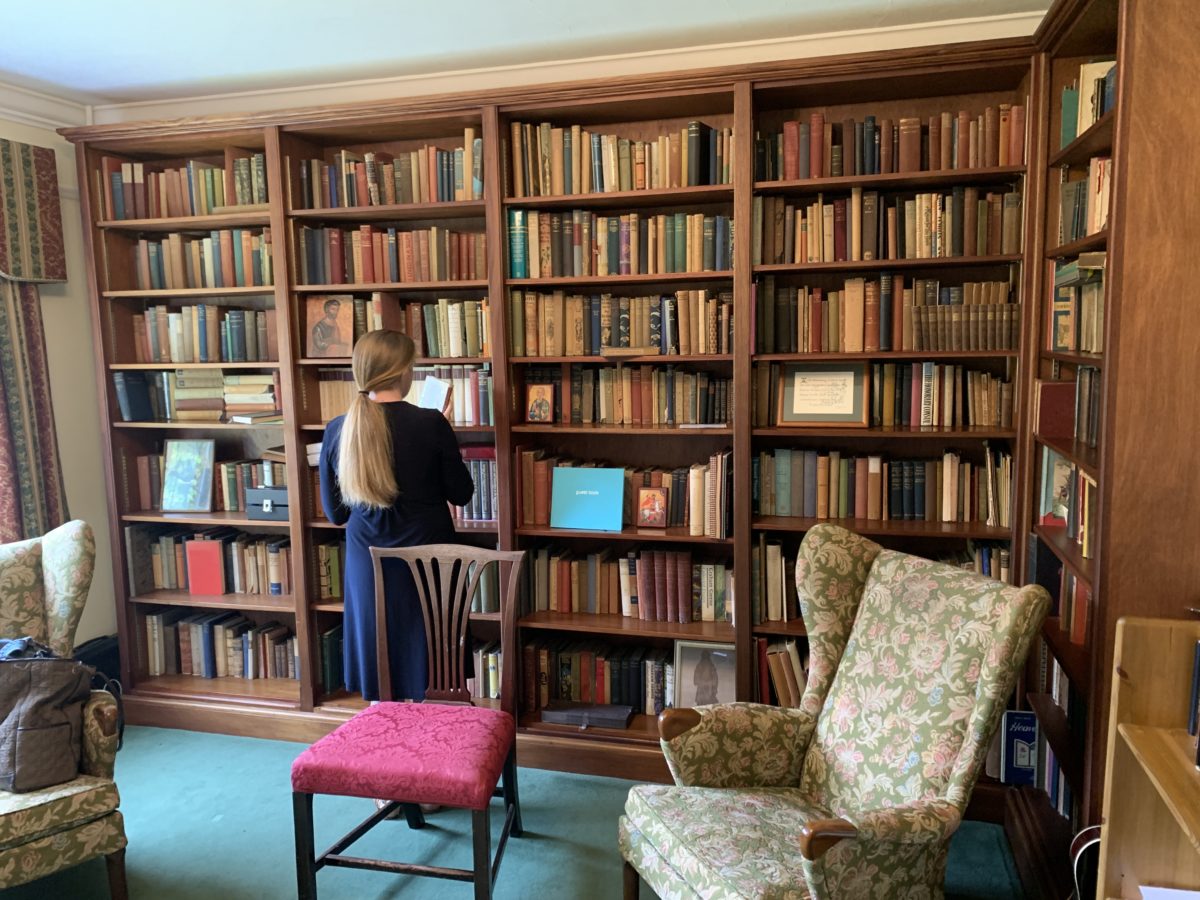

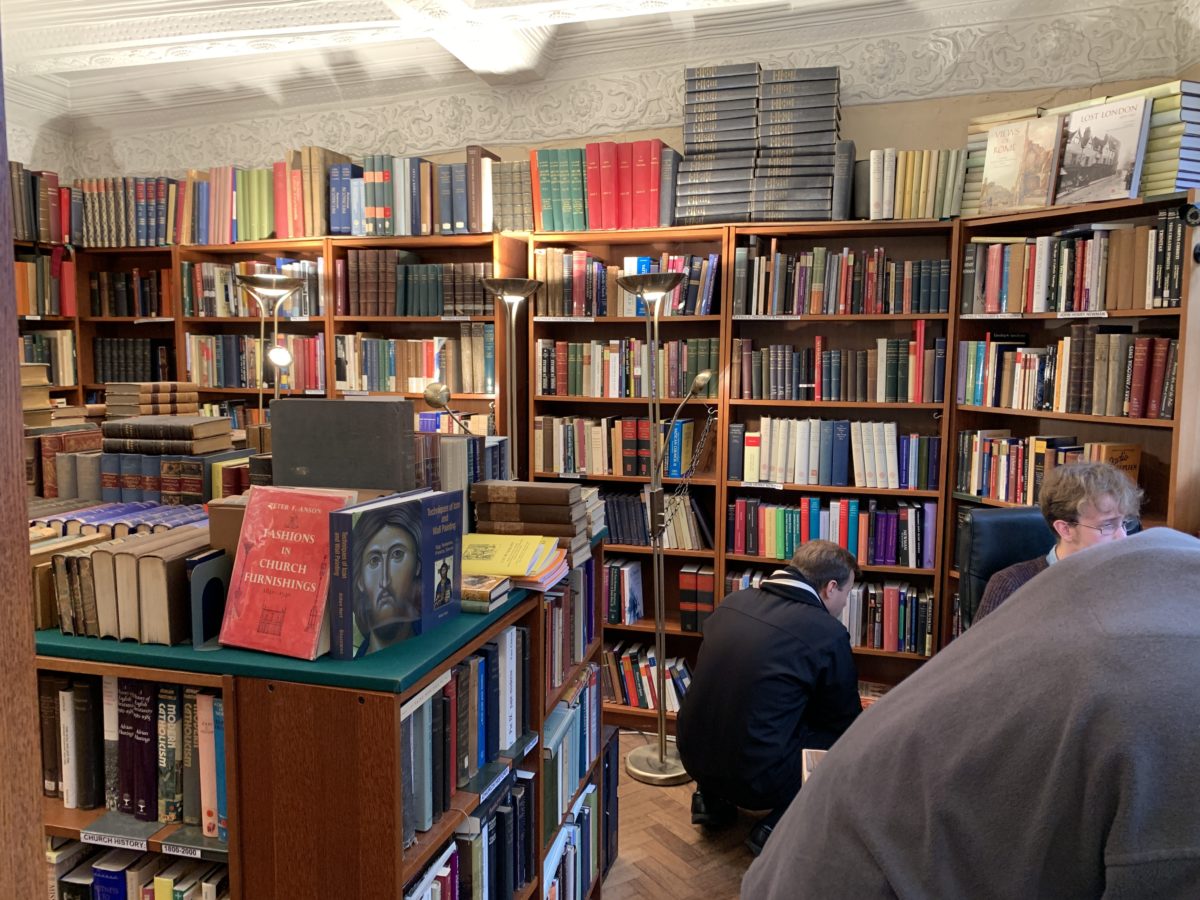

Canon Udris showed us the whole collection, on display in the parish office, which spans five full bookcases—38 shelves in total. The collection is arranged alphabetically by author, but beyond that, the items haven’t been arranged in terms of importance, giving it all the delight of an old used bookstore, with random stacks holding undisclosed treasures.

Canon Udris asked Kathleen and I, “Well, how about I give you guys a little time in here on your own, to poke around the books?” We glanced at each other and said, “Uh, yes. That would be amazing.” Canon Udris replied, “Great! How much time should I give you?” I immediately replied, “Thirty six hours.” He laughed and we settled on a more reasonable hour and a half.

Spending ninety minutes picking up these books and flipping through the pages, touching the doodles and inscriptions, knowing that Chesterton’s own hands picked up these same books, reading and enjoying them, was almost as stirring as the mystical experience after communion. The word I kept recalling was “incarnation.” Books, relics, churches, statues—they all incarnate Gilbert Keith Chesterton, making him real and substantial, not just an abstract hero known only through words. He is real.

G.K. Chesterton’s Grave (Shepherd’s Lane Cemetery)

30 Orchard Rd, Beaconsfield HP9 2DZ, UK

When Chesterton died, they processed his body down the streets of Beaconsfield, taking a circuitous path to make sure they passed the homes and shops of the ordinary townspeople of Beaconsfield, the people who knew Gilbert best and loved him most. Many waited outside, waving and smiling. By all accounts, the procession was joyful, not sad.

Chesterton was buried at Shepherd’s Lane Cemetery—about a 15-minute walk from Top Meadow. When you enter the cemetery, his grave is on the right side, in the Catholic area of the cemetery. There lies one gravesite in which Gilbert was buried in 1936, then his wife Frances above him in 1938, then Dorothy Collins above her in 1988.

As mentioned above, the gravestone featuring a beautiful sculpture of the crucified Christ with his Mother standing next to him is actually a replica. The original stone was designed by the famous sculptor Eric Gill, who helped found the Ditchling community of Distributists and was a profound admirer of Chesterton. (Gill also designed the Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral, in the same style as the Chesterton tombstone, and a large altarpiece memorial to the 40 English martyrs, which you'll see below.) The original Chesterton tombstone hangs on a wall outside St. Teresa’s church in Beaconsfield, and strangely it seems to be in better shape than the newer replica, which has been there less than ten years but is already quite deteriorated.

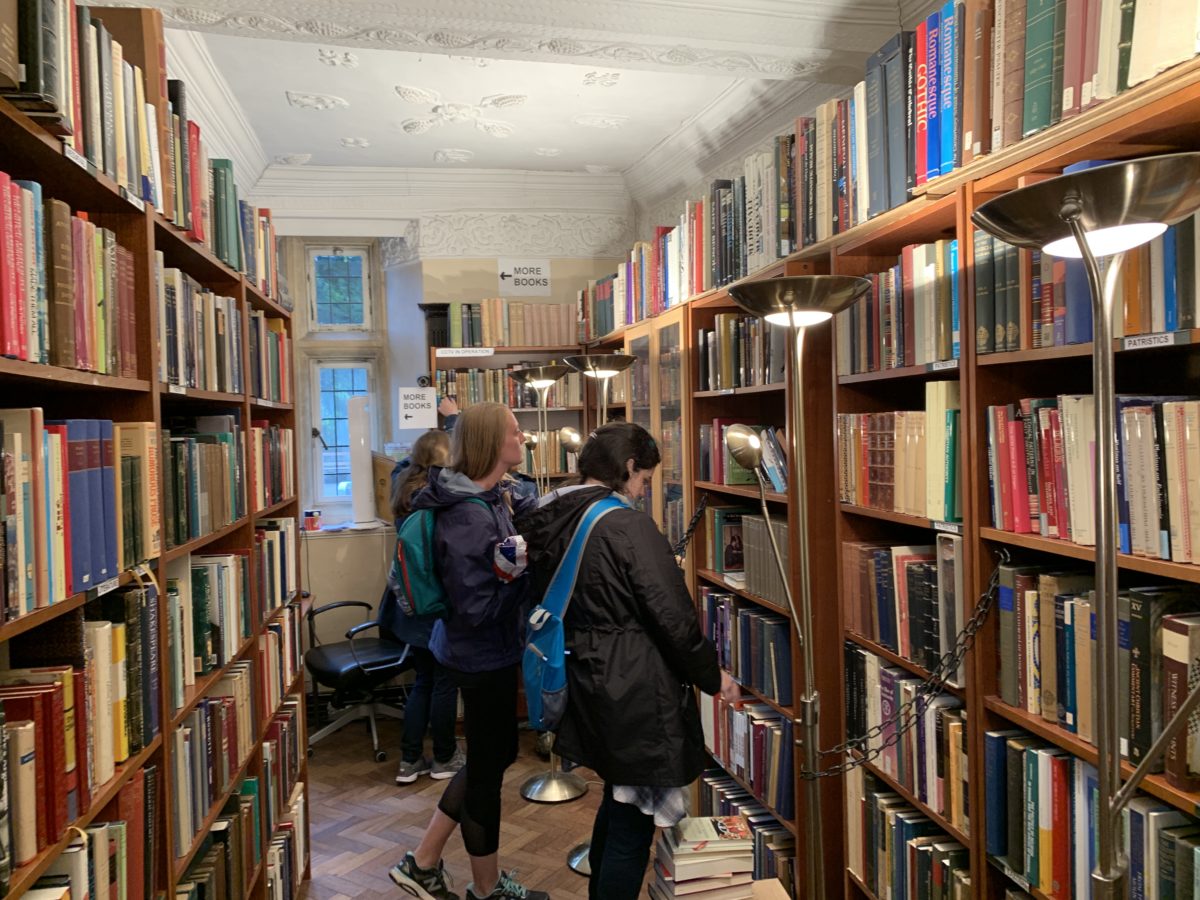

The G.K. Chesterton Library

25 Woodstock Rd, Oxford OX2 6HA, UK

After G.K. Chesterton died, most of his books and papers were sent to the British Library. However, some years later, the British Library wanted to get rid of some items, so they asked Chesterton devotee Aidan Mackey if he was interested in receiving them. Aidan agreed, and soon several boxes showed up on his doorstep, containing much of Chesterton’s personal library, manuscripts, doodles, letters, and more. That was the seed of the famous G.K. Chesterton Library collection.

Watch this two-minute video of Aidan telling the story:

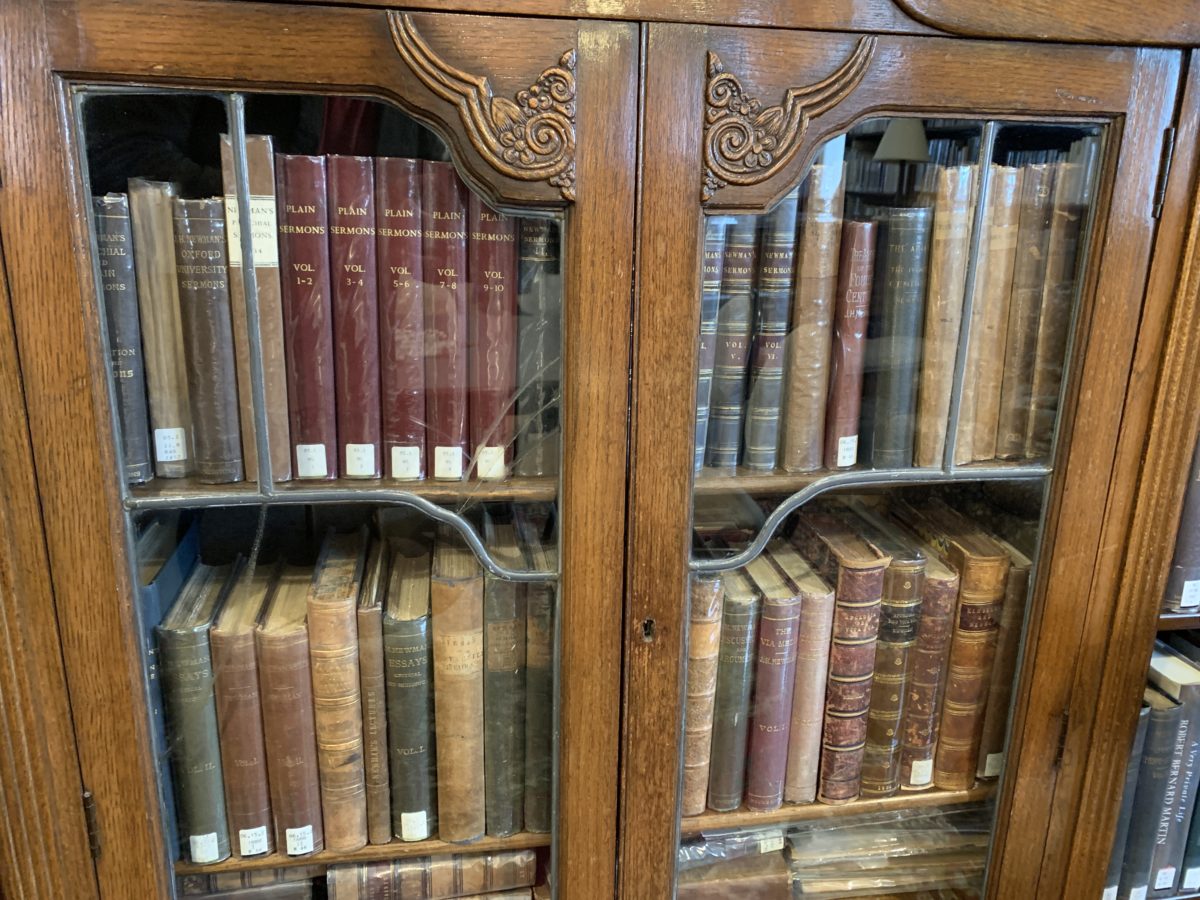

Aidan later moved the collection to the second floor of the beautiful Oxford Oratory, and continued adding to it over the years, acquiring new Chesterton items via auctions, donations, and friends. I believe it's now the most extensive collection of Chesterton memorabilia anywhere in the world.

Aidan was scheduled to give us a tour, but something came up, and we were instead guided by Fr. Jerome Bertram, one of the kindly Oratorian fathers (who could use our prayers—he's in the final months of his life.) We couldn’t believe our luck when Fr. Jerome said he had to sit down, but that we could feel free to examine anything we wanted in the library—nothing off limits.

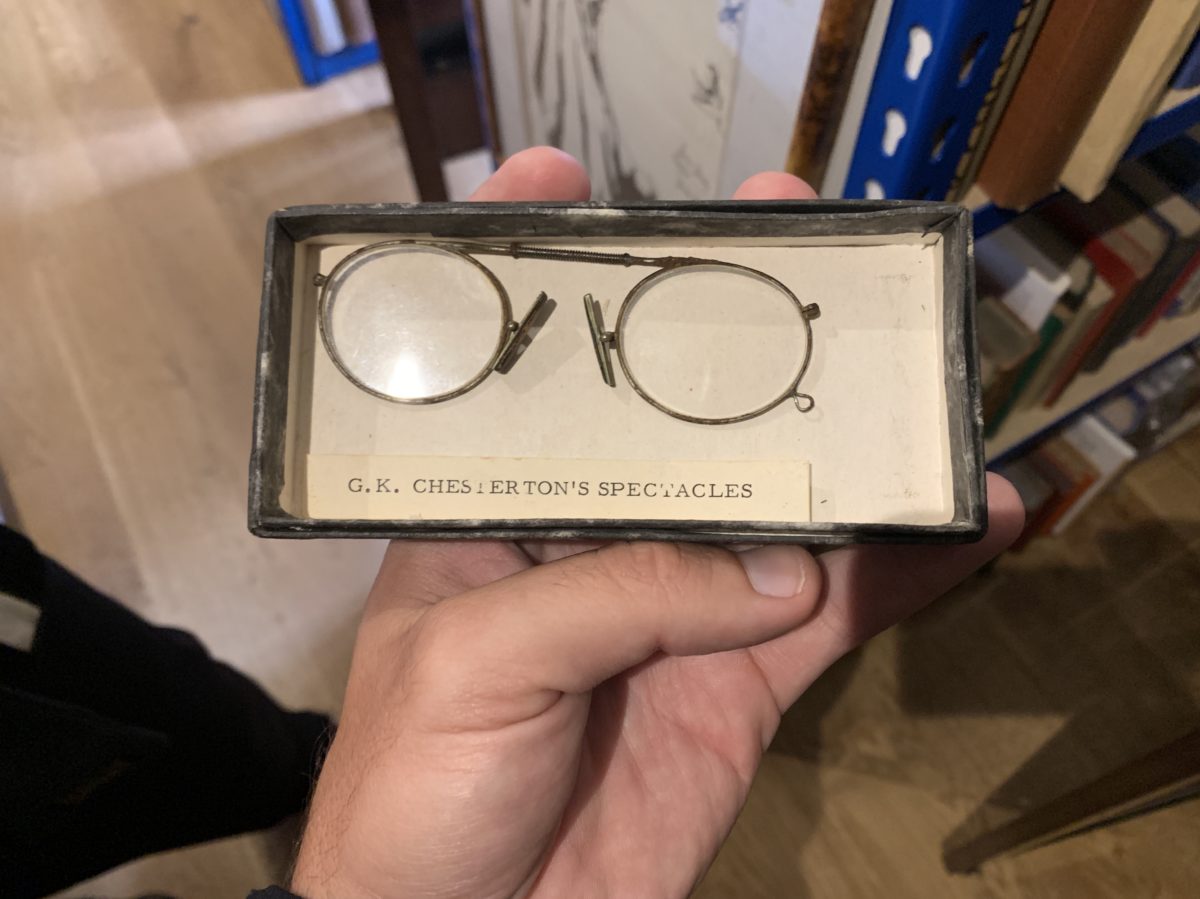

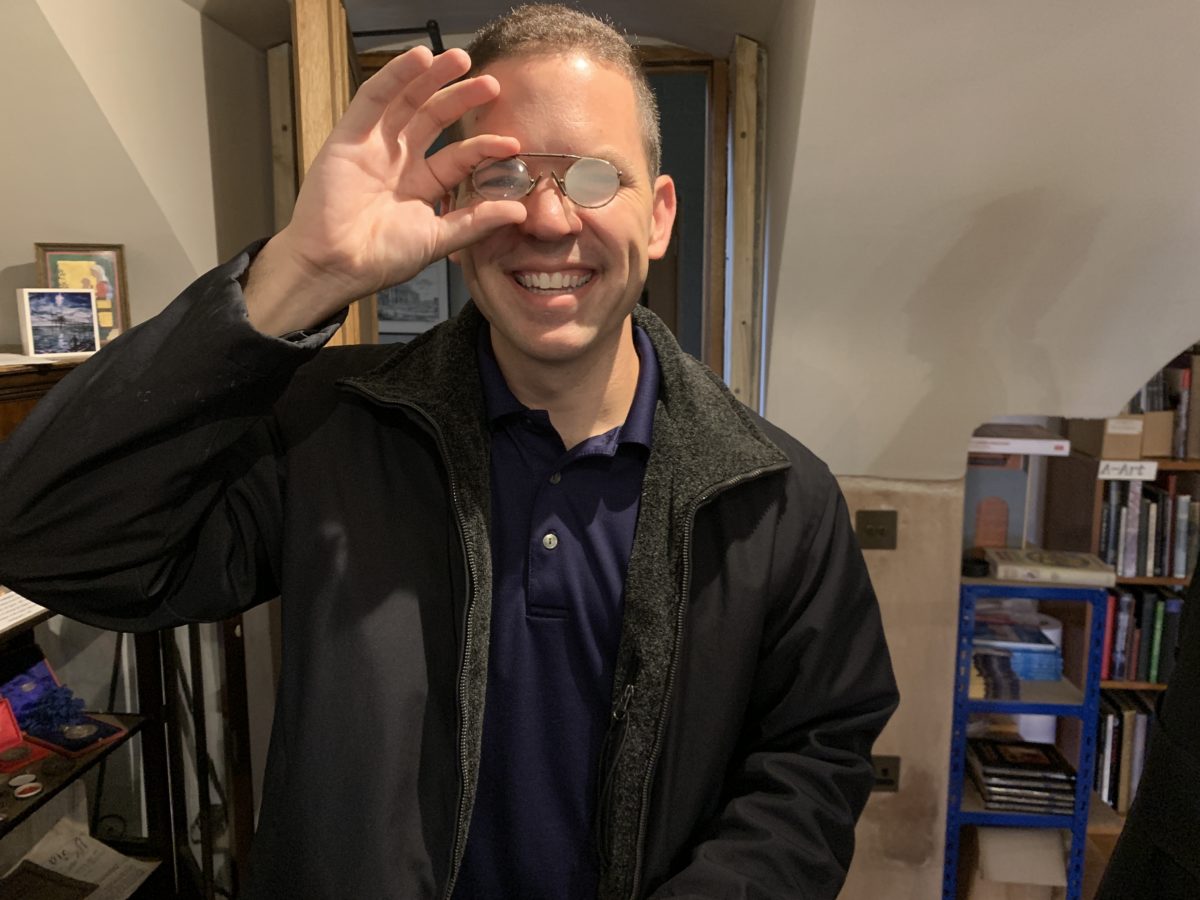

Within seconds we were holding Chesterton’s walking stick, spectacles, and hat, touching his typewriter, thumbing through his books and doodles, examining his toy theater. We held his favorite pen. When Chesterton was on his deathbed, Fr. Vincent McNabb walked over to the table, picked up the pen, and kissed it, reverencing the sword with which Gilbert heroically fought his many battles.

I’m still trying to process the whole experience. Chesterton is my greatest hero, and having several unrestricted hours to explore this collection was a pinnacle experience of my life.

At the time of our visit, the Library was closed to the public and only available through private tours. But it was recently announced that the University of Notre Dame’s campus in London has acquired the entire collection, with plans to create a new permanent, public exhibition in their space near Trafalgar Square in London. In fact, we were among the last people to tour the collection before its move. Everything was to be packed up within a few weeks after our visit.

The new transition is great news for Chesterton fans, because it means the items will be easier to access, better archived and preserved, and the new exhibit will offer greater exposure to Chesterton. The Notre Dame folks even plan to create a full, working model of Chesterton's famous toy theater so we can see his little puppets and cutouts in their intended setting!

The location of the exhibit, in their campus right off Trafalgar Square, is great, too. The hope is that London tourists will drift into the new museum and discover one of England’s premiere thinkers and writers. They don't have a formal open date, but I've heard rumblings it will debut in September/October 2020.

Here's a look at some of the gems we found in the Library, which was probably the highlight of our entire pilgrimage:

Statue of G.K. Chesterton in front of the paper from Pope Pius XI, giving Chesterton his apostolic blessing. After Chesterton's death, a telegram was sent on Pope Pius XI's behalf by Cardinal Pacelli, who would himself become Pope Pius XII. It read: "Holy Father deeply grieved death Mr. Gilbert Keith Chesterton devoted son Holy Church gifted Defender of the Catholic Faith. His Holiness offers paternal sympathy people of England assures prayers dear departed, bestows Apostolic Benediction."

Chesterton's pocket watch. With how often Chesterton was late to events, it's unlikely this was of much help.

Sitting at G.K. Chesterton's table (custom made for him), with his hat, typewriter, and walking stick. The stick was the “snakewood” stick that the Knights of Columbus presented to Chesterton in New Haven, CT, during one of his American visits, and it was the stick he chose to have with him the day he was received into the Catholic Church in 1922.

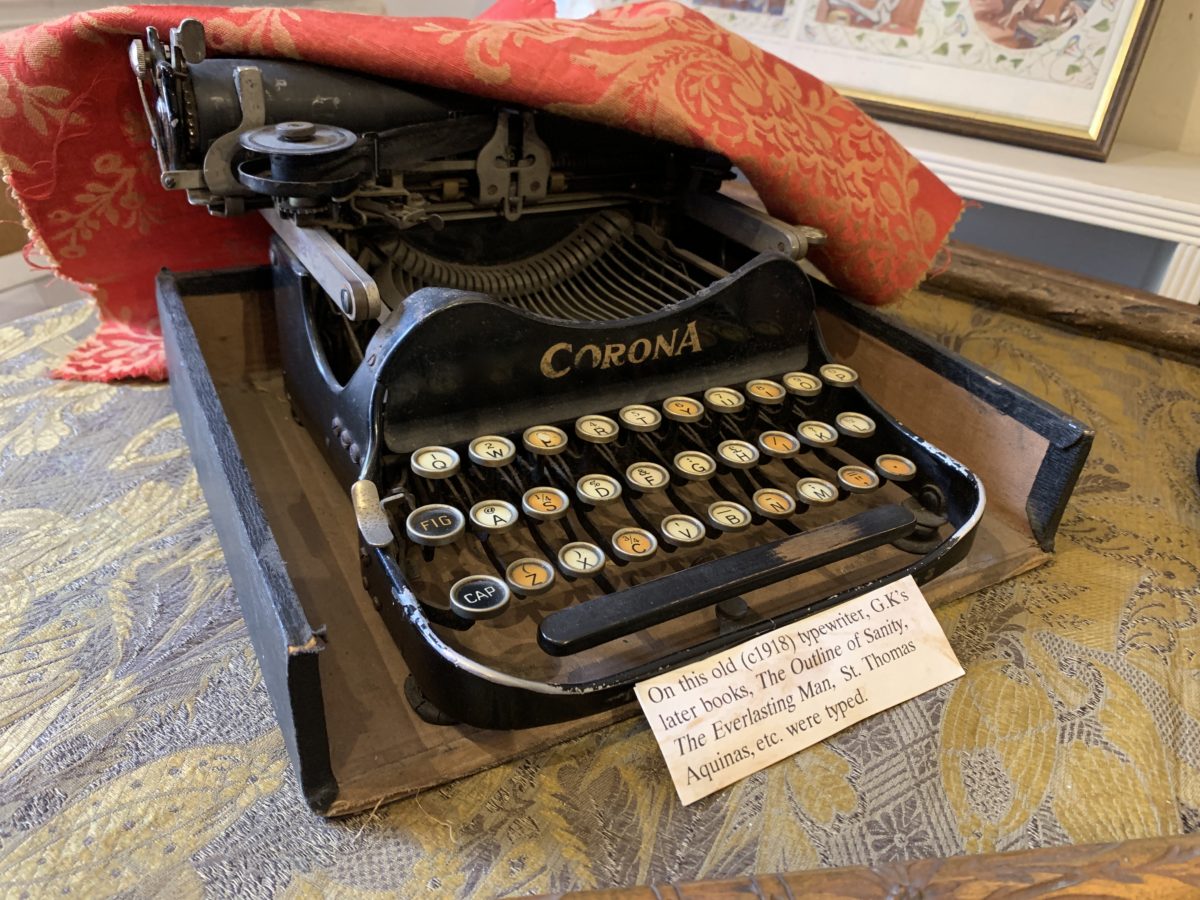

Closeup of the Chestertons' typewriter. The note says: "On this old (c. 1918) typewriter, G.K.'s later books, The Outline of Sanity, The Everlasting Man, St. Thomas Aquinas, etc. were typed." Chesterton himself didn't type much, so it would have been his secretaries taking dictation with the typewriter.

Unsheathing a Chestertonian sword-stick, which he often carried around town (although this is only a replica, not actually Chesterton's.) The books on the shelf are all from Chesterton's personal library, and many are marked up with notes and doodles.

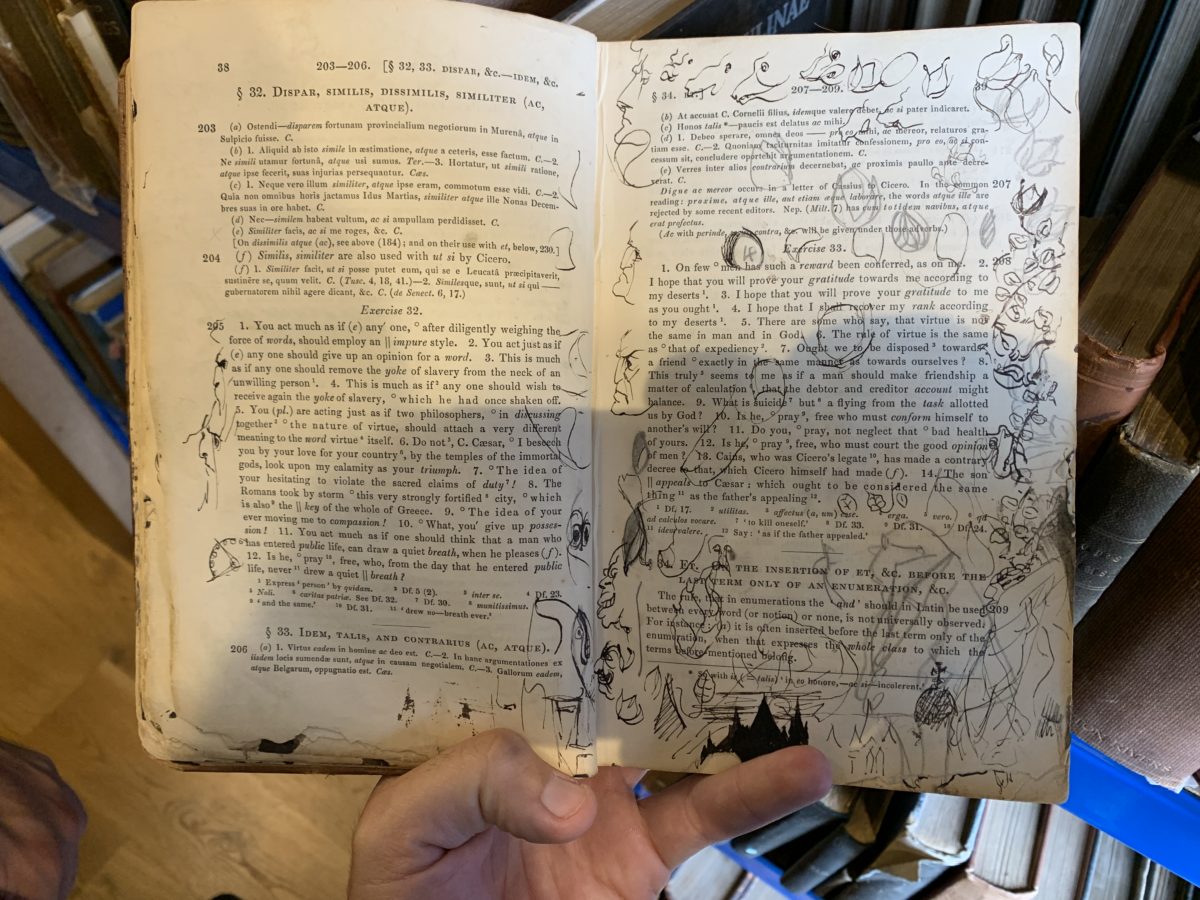

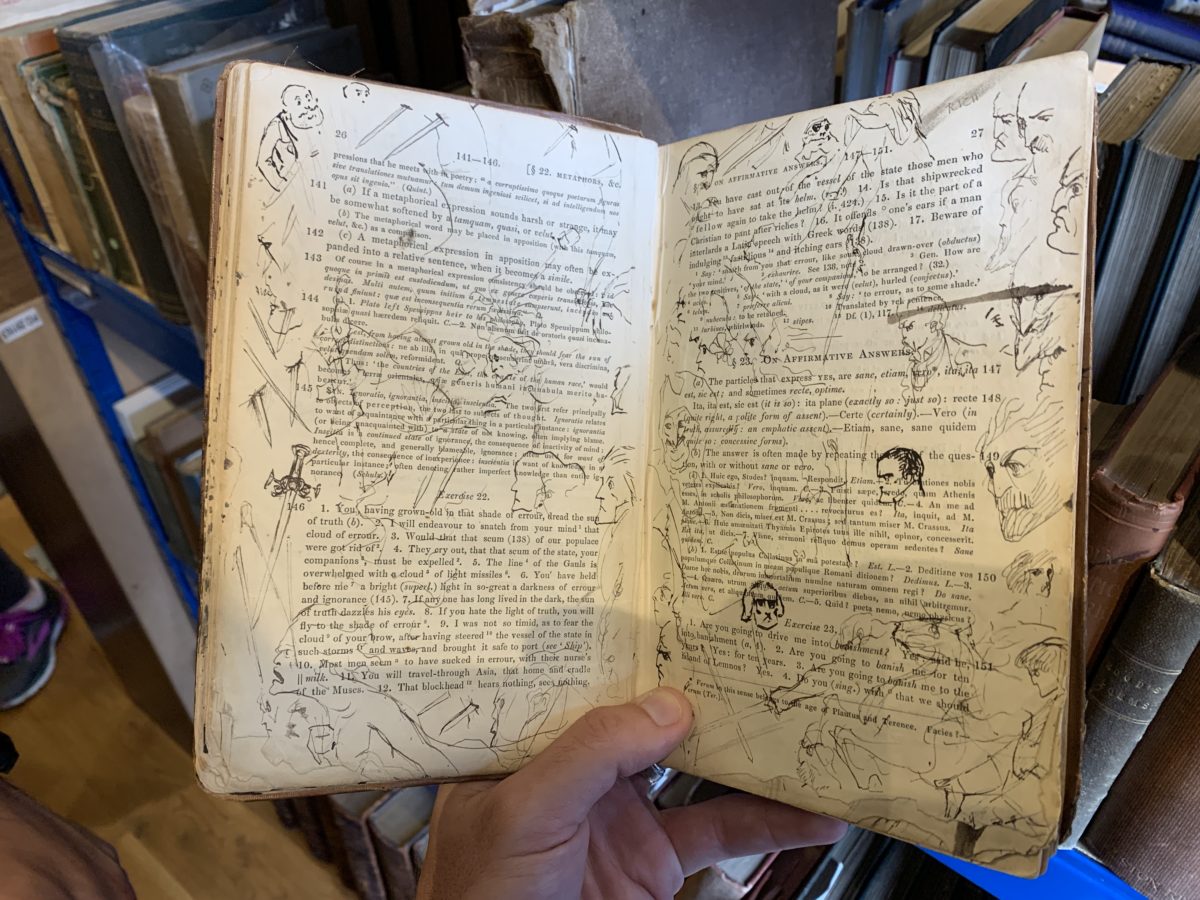

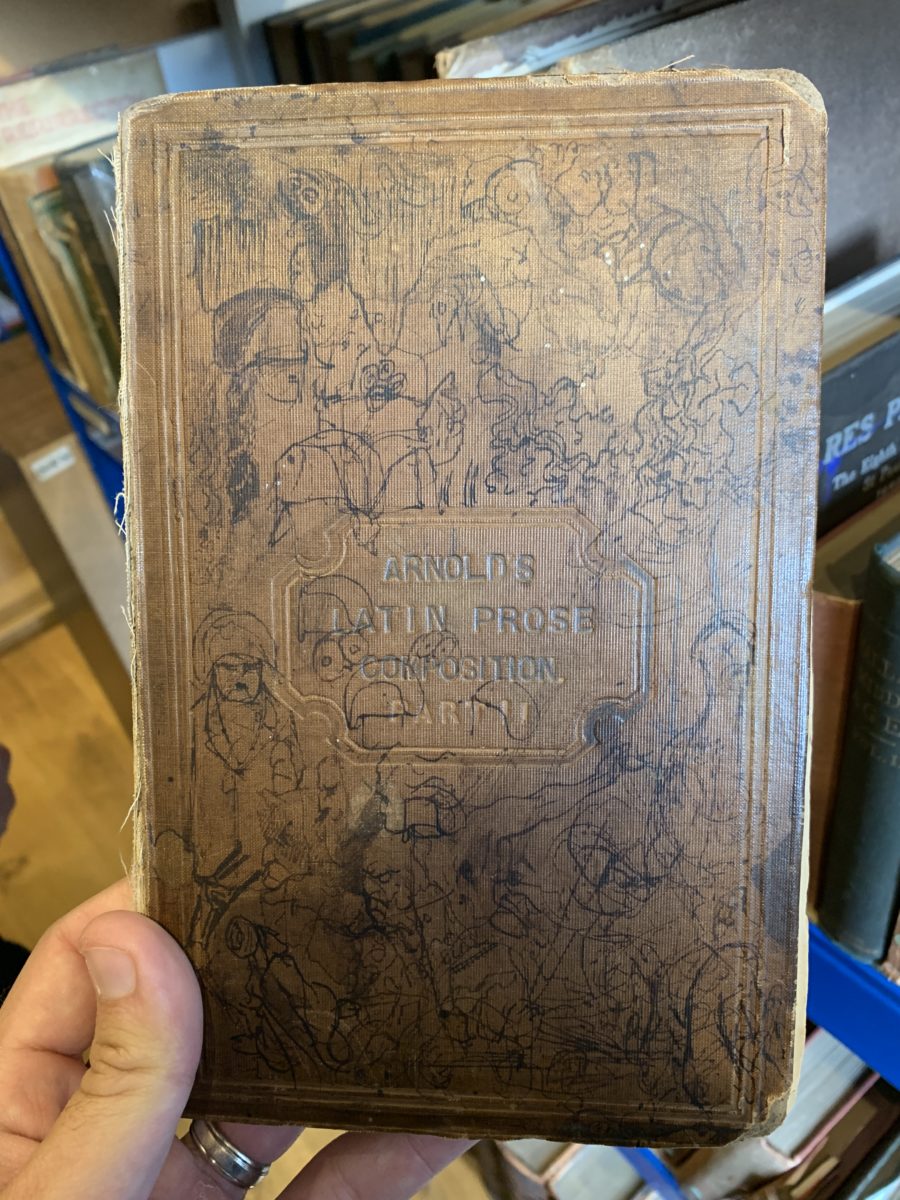

Chesterton's boyhood Latin composition book. It's definitely the most marked-up book in the collection. Just look at that cover!

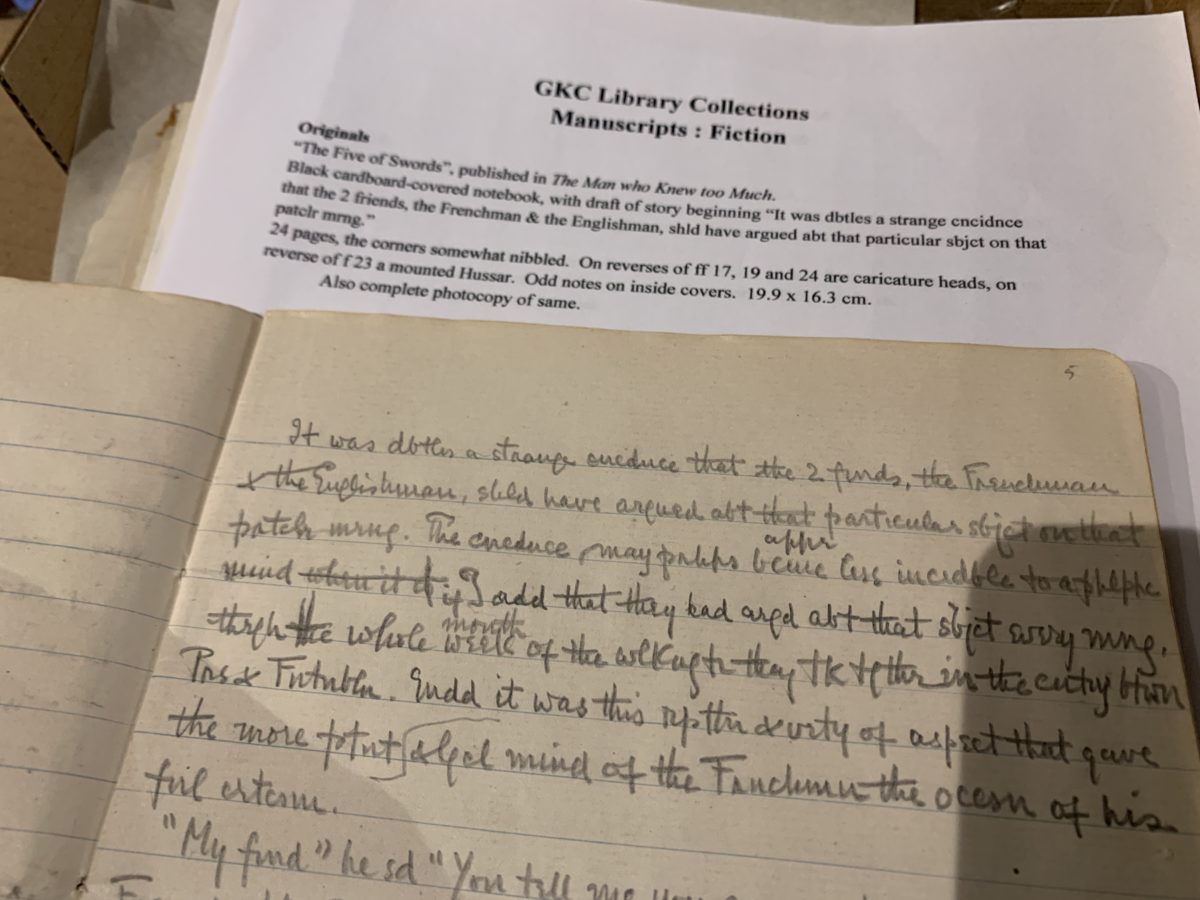

One of Chesterton's notebooks, which contains an original draft of his story "The Five of Swords," which appeared in "The Man Who Knew Too Much."

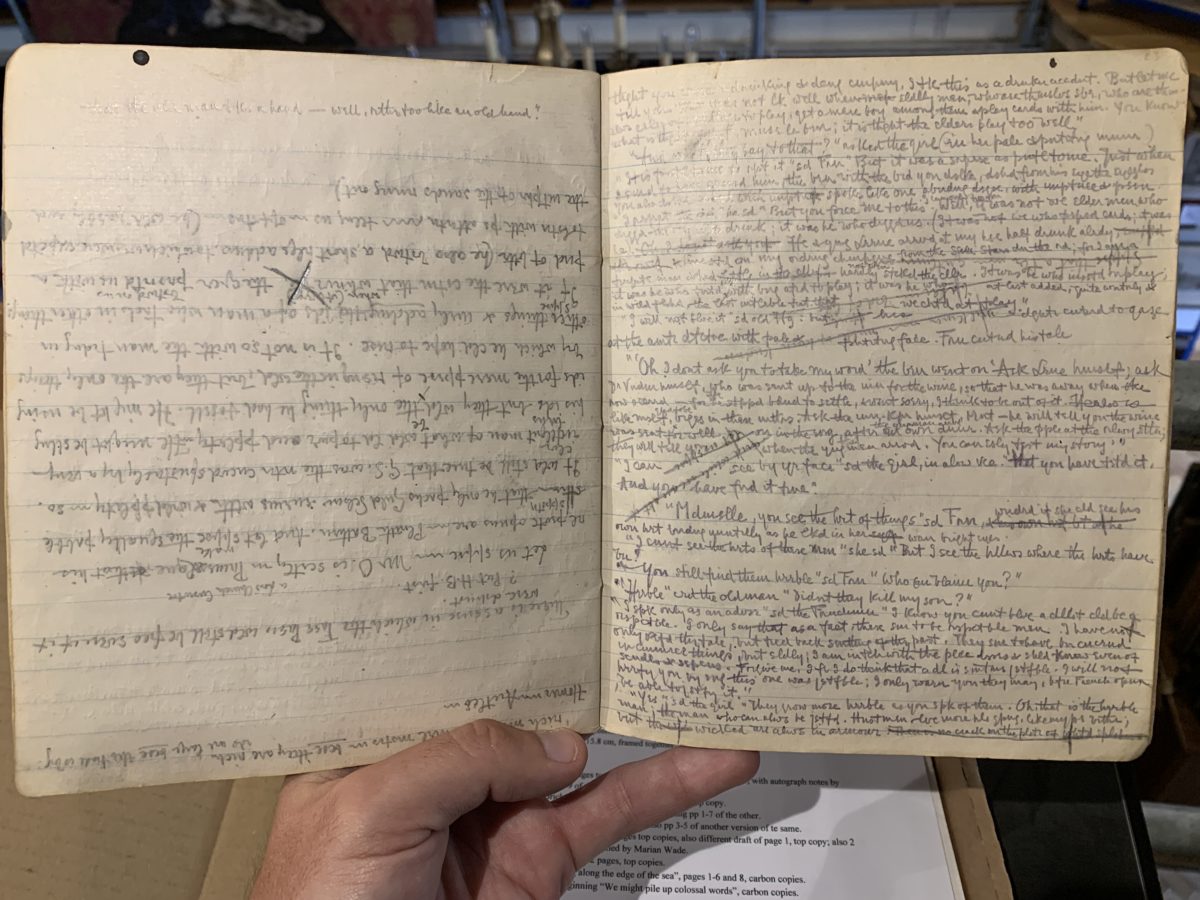

More pages from the draft of "The Five of Swords." Notice how after finishing the notebook, he flipped it upside down and kept going on the backs of the pages!

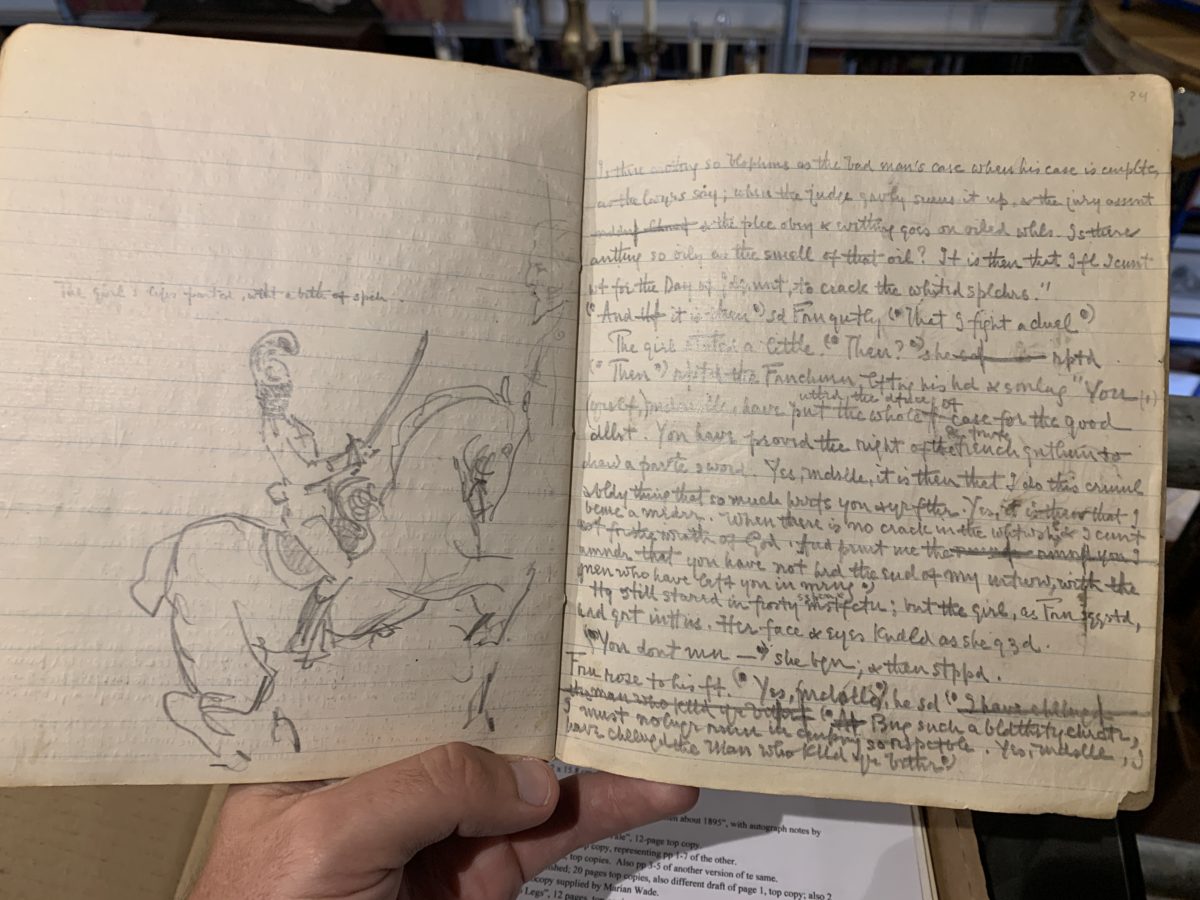

More pages from the draft of "The Five of Swords." You see the close connection between Chesterton the artist and writer. He thought in pictures, and illustrated his stories as he wrote them.

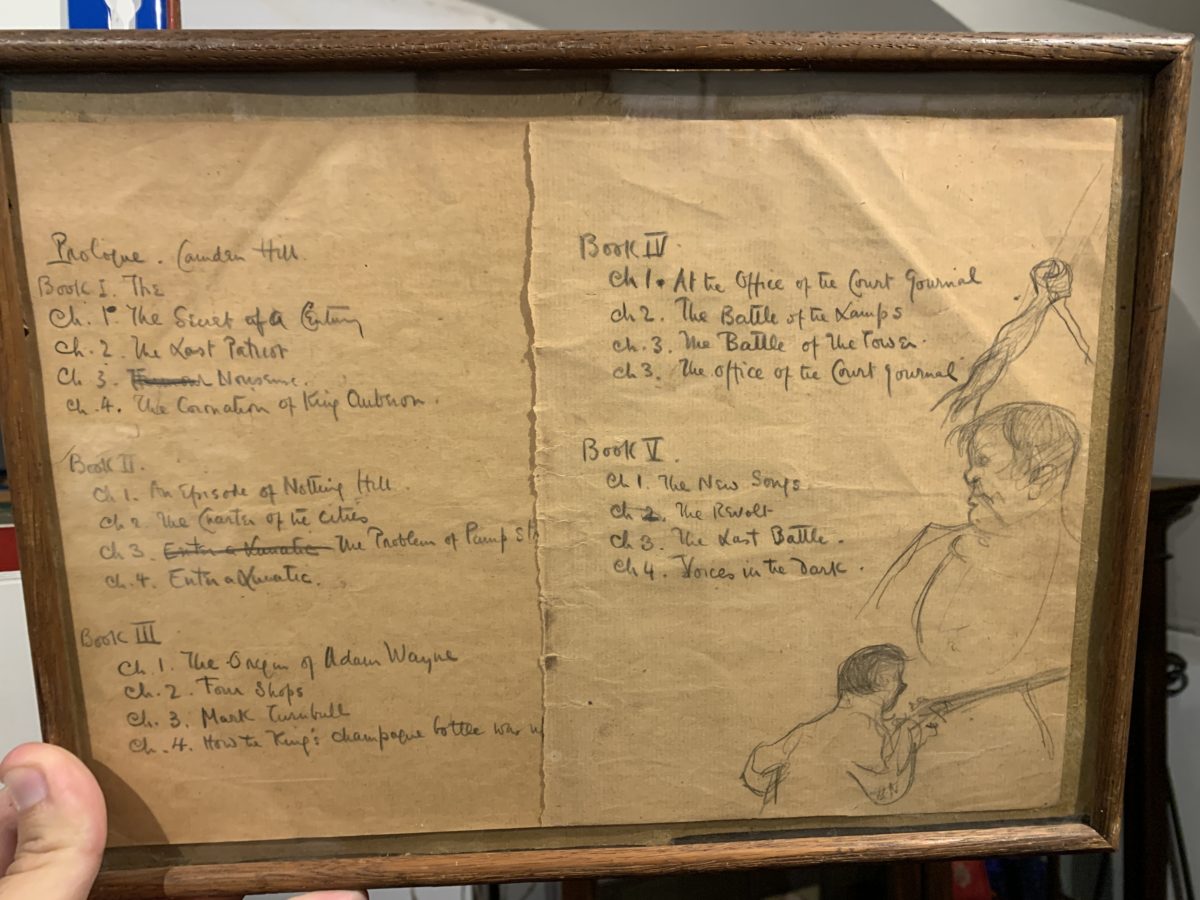

Original draft of the chapter headers for Chesterton's first novel, "The Napoleon of Notting Hill," but they bear almost no resemblance to those actually used in the book. Gilbert frequently jotted down titles for stories, poems, and plays before composing the piece itself.

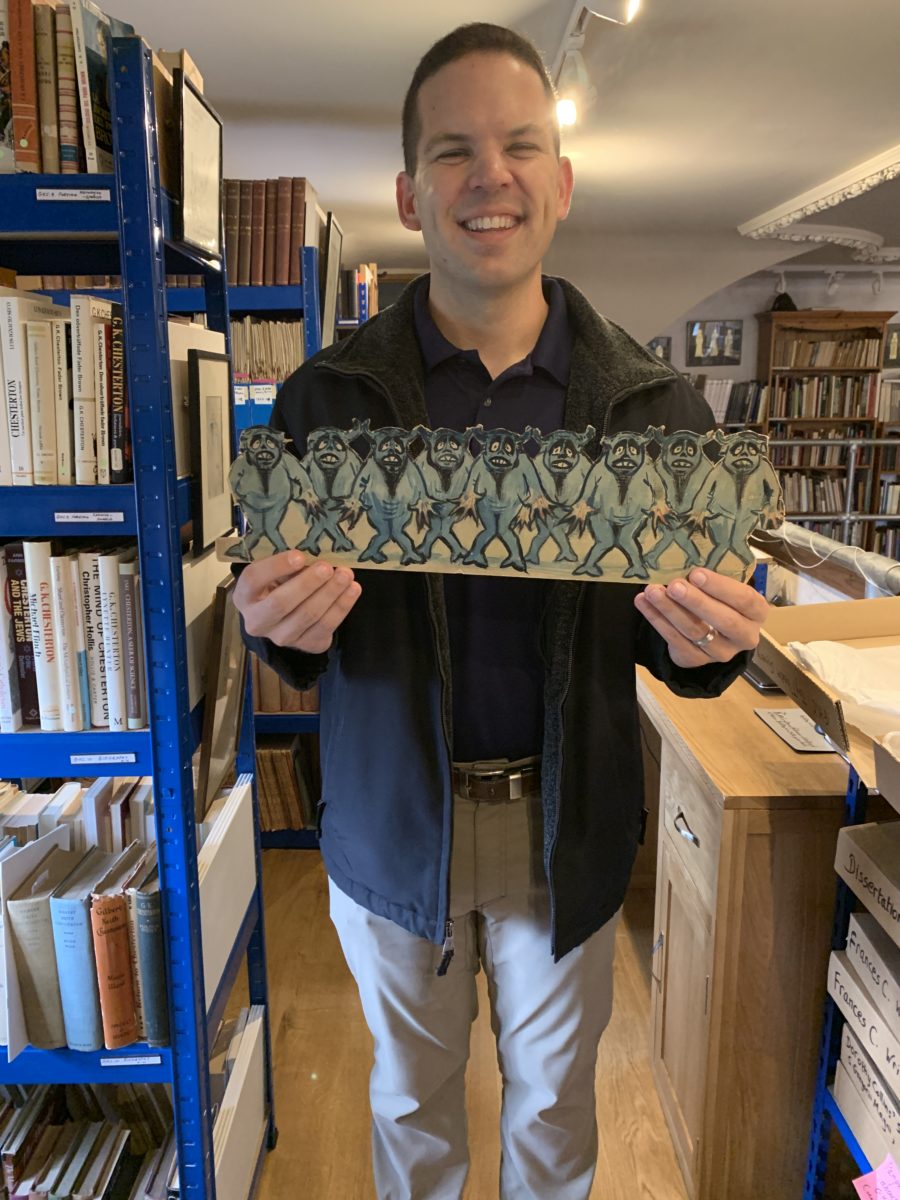

Props from Chesterton's toy theater. He built the theater himself, based on one his father had made. He also cut out and painted different characters and scenery, and then devised the plots of the plays. Two of his most popular were “St. George and the Dragon” and “The Seven Champions of Christendom.”

C.S. Lewis

C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) was one of the most popular writers of the twentieth century, and the greatest Christian apologist. He wrote around 40 books in several different genres, including the Chronicles of Narnia series, his sci-fi Ransom Trilogy, and several books on Christian theology such as Mere Christianity and The Screwtape Letters.

Lewis was a trained academic and spent most of his life as professor of English literature at Oxford University, followed by nine years at Cambridge. Along with his close friend, J.R.R. Tolkien, he was a leader of the Inklings, an Oxford literary group that met throughout the mid-twentieth century at pubs where they discussed their latest works.

The Kilns

Lewis Cl, Oxford OX3 8JD, UK

This was C.S. Lewis's home for most of his adult life, from 1930-1963, and the place where he died. As a young man during World War I, Lewis and his close friend Paddy Moore made a promise that if one of them fell in battle, the other would care for his family. When Paddy was killed, Lewis made good on his promise, taking in Paddy's mother, Mrs. Janie Moore, and with her daughter, Maureen Dunbar. Together with Lewis' brother, Warnie, the four moved into the Kilns.

The two Lewis bachelors and Moore women lived in what was, admittedly, an unorthodox arrangement, especially for Lewis who was a young student at Oxford. To avoid gossip and speculation, they chose to live outside the Oxford center. The Kilns is located in Headington Quarry, about five miles east of Oxford.

The house itself is charming, and the surrounding area is lush and beautiful. A six-acre "C. S. Lewis Nature Reserve" now sits next to the house, a tranquil woodland with pathways and a large pond.

Inside the Kilns, we were given a tour by one of its resident scholars. The Kilns is currently owned by the C.S. Lewis Foundation and they use it as a residential study center with a handful of live-in students, most doing scholarship at Oxford. The students also help give tours of the Kilns. (Note: tours are held by private appointment and only on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. So plan accordingly.)

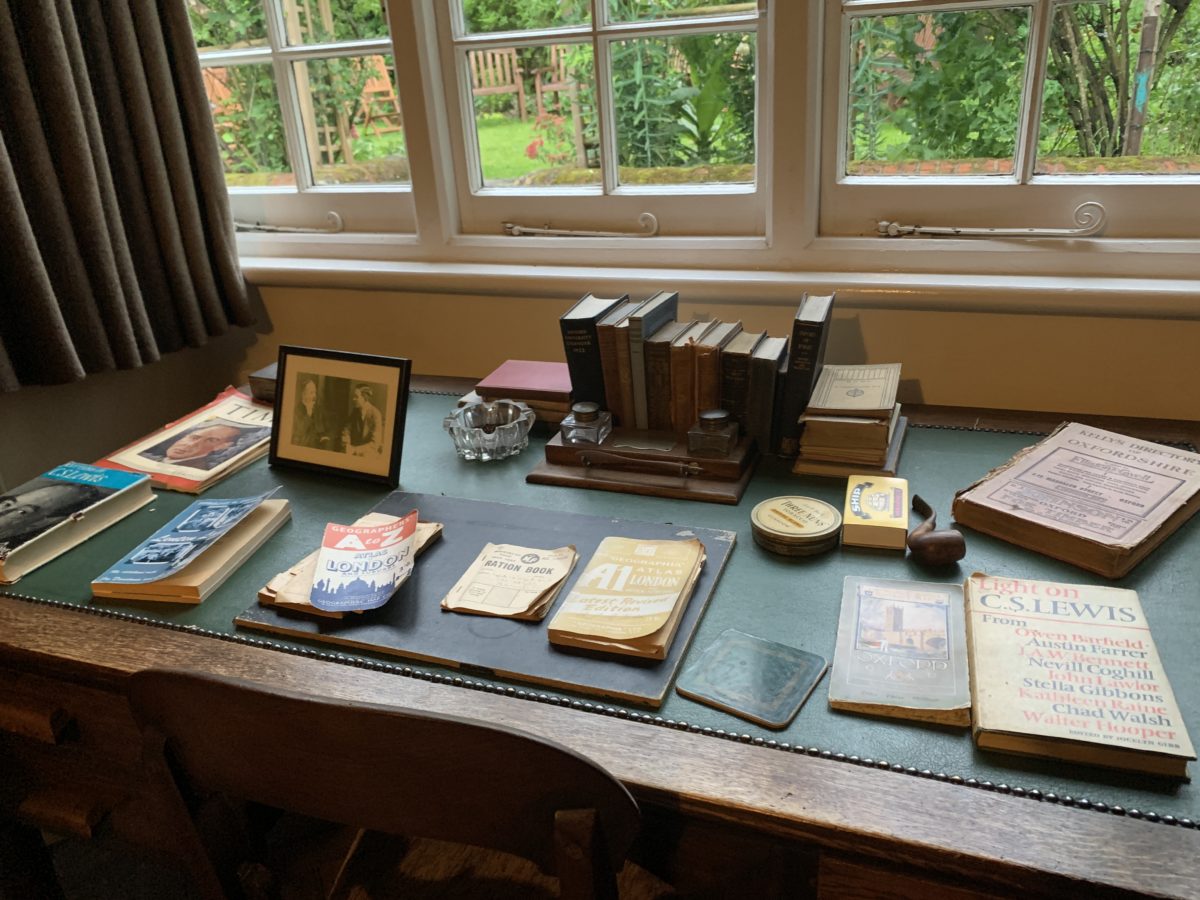

The Kilns has changed hands many times since Lewis' death and little of the furniture and decor are original. But the house has been made up to resemble how it would have looked in Lewis' time. The two most famous Lewis artifacts in the world—his writing desk, where he wrote most of his books, and the wardrobe that inspired The Chronicles of Narnia—are actually located at the Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College, near Chicago.

But there were still some neat items at the Kilns, including:

- The original sign that hung in front of the "The Eagle and Child" pub (more on this pub below). The owners were replacing the sign when Lewis' secretary, Walter Hooper, heard about it. Hooper was able to acquire the original sign and bring it to the Kilns.

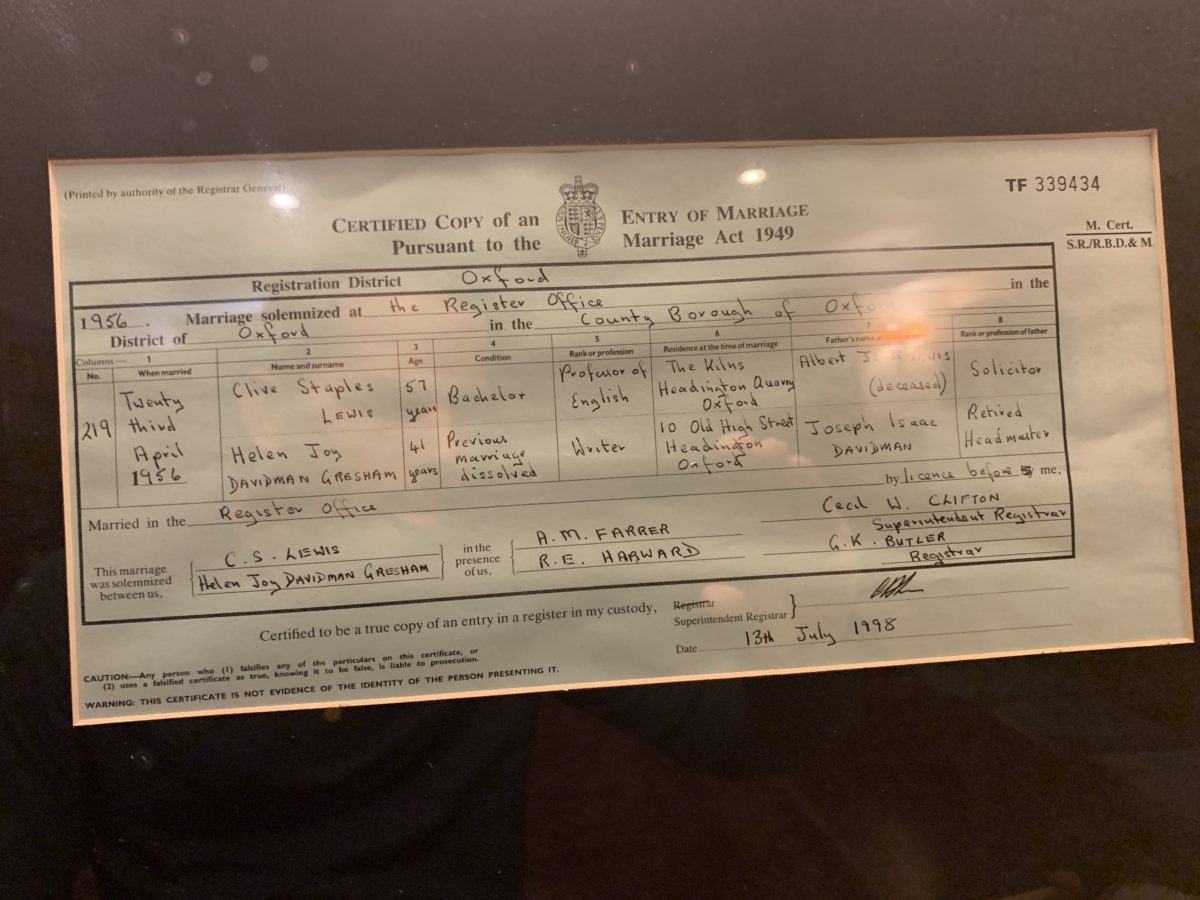

- Copy of the wedding certificate between C.S. Lewis and Joy Davidman from 1956. Lewis and Davidman were simply friends at the time of their civil marriage, which Lewis did as a favor so that Joy could continue living in England. He told a friend that "the marriage was a pure matter of friendship and expediency." But they later fell in love—after they were married—and sought a Christian marriage in the Church of England. Watch the movie Shadowlands for a fictional account, or for a truer account read the biography Joy: Poet, Seeker, and the Woman Who Captivated C. S. Lewis.

- Lewis' bedroom, where he died under a picture of the Shroud of Turin. Many people know that Lewis died on November 22, 1963, the same day that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated and Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World, also passed away. (Peter Kreeft has a delicious book called Between Heaven and Hell, imagining an afterlife dialogue among the three men.) But what I didn't know until I entered Lewis' bedroom, where he collapsed and died, was that hanging over the mantle is a framed picture of Christ's face from the Shroud of Turin. The Shroud is a haunting relic that has captivated people for hundreds of years, believed to be the actual burial cloth of Christ. The Shroud is usually associated with Catholics, which only adds to the speculation that Lewis may have become Catholic had he lived another decade or so. (His secretary, Walter Hooper, himself a convert to Catholicism, is convinced Lewis would have become Catholic, too, given the progressive direction of the Church of England, especially after permitting woman priests in 1994.)

- The Chesterton honeysuckle plant outside. When Gilbert and Frances Chesterton were married in 1901, Frances had a honeysuckle wedding bouquet. She saved cuttings from it and planted them in front of their homes in London and Beaconsfield. Years later, Aiden Mackey, a great Chesterton devotee, brought clippings from the Beaconsfield plants and rooted them in front of the Kilns. It's neat to look at that plant in front of Lewis' home and realize that it stems, quite literally, from the wedding of Gilbert and Francis Chesterton. (We tried bringing home a few clippings to Florida, and though we successfully smuggled them through customs, the plants simply couldn't survive the hot, humid Florida weather.)

C.S. Lewis' bedroom at the Kilns, accessible by the outdoor stairs. You can see the blue historical plaque hiding above the door (enlarged below).

Historical plaque outside the Kilns, C.S. Lewis' house. It reads: "C.S. Lewis 1898-1963 Scholar and Author lived here 1930-1963".

Photo of what the Kilns looked like in Lewis' day. Note the two giant kilns in the middle, hence the name. The house was originally the site of a brickworks.

C.S. Lewis' sitting room at the Kilns. In Lewis' time, visitors remember the carpeted floor being covered in ash, as Lewis and his brother Warnie scattered their cigarette and pipe ashes on them for over thirty years.

Another visiting room at the Kilns. None of the books belong to Lewis. His personal library now resides in the Marion E. Wade Center, near Chicago.

Copy of the marriage certificate between C.S. Lewis and Joy Davidman Gresham, signed by Fr. Austin Farrer, the Anglican theologian and priest. Lewis dedicated his book "Reflections on the Psalms" to Fr. Farrer.

The original sign for the "Eagle and Child" (aka the "Bird and Baby") which hung in front of the pub in the years when C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and the other Inklings met there. Walter Hooper, Lewis' secretary, rescued the sign when the owners were replacing it, and brought it to the Kilns.

Cool little room in the upstairs attic of the Kilns. As the sign says: "This area recreates the Little End Room in Ireland where, as boys, Jack (C.S. Lewis) and Warnie entered their imaginative world of Boxen." Read the posthumously published "Boxen" for the full story. When you flick a switch in the room, the wardrobe door automatically opens to reveal a snowy wonderland. Watch the video below.

Fireplace in C.S. Lewis' bedroom. Note the image of the Shroud of Turin hanging over the mantle. It would have been among the last things Lewis saw before he died in this room. Our tour guide confirmed the image was there in Lewis' time.

C.S. Lewis Community Nature Preserve, a six-acre tranquil woodland with pathways and a large pond, which sits right next to the Kilns.

The famous honeysuckle plant at the Kilns. When Gilbert and Frances Chesterton were married in 1901, Frances had a honeysuckle wedding bouquet. She saved cuttings from it and later planted them in front of their home in Beaconsfield. Years later, Aiden Mackey, the great Chesterton devotee, brought clippings from the Beaconsfield plants and rooted them in front of the Kilns.

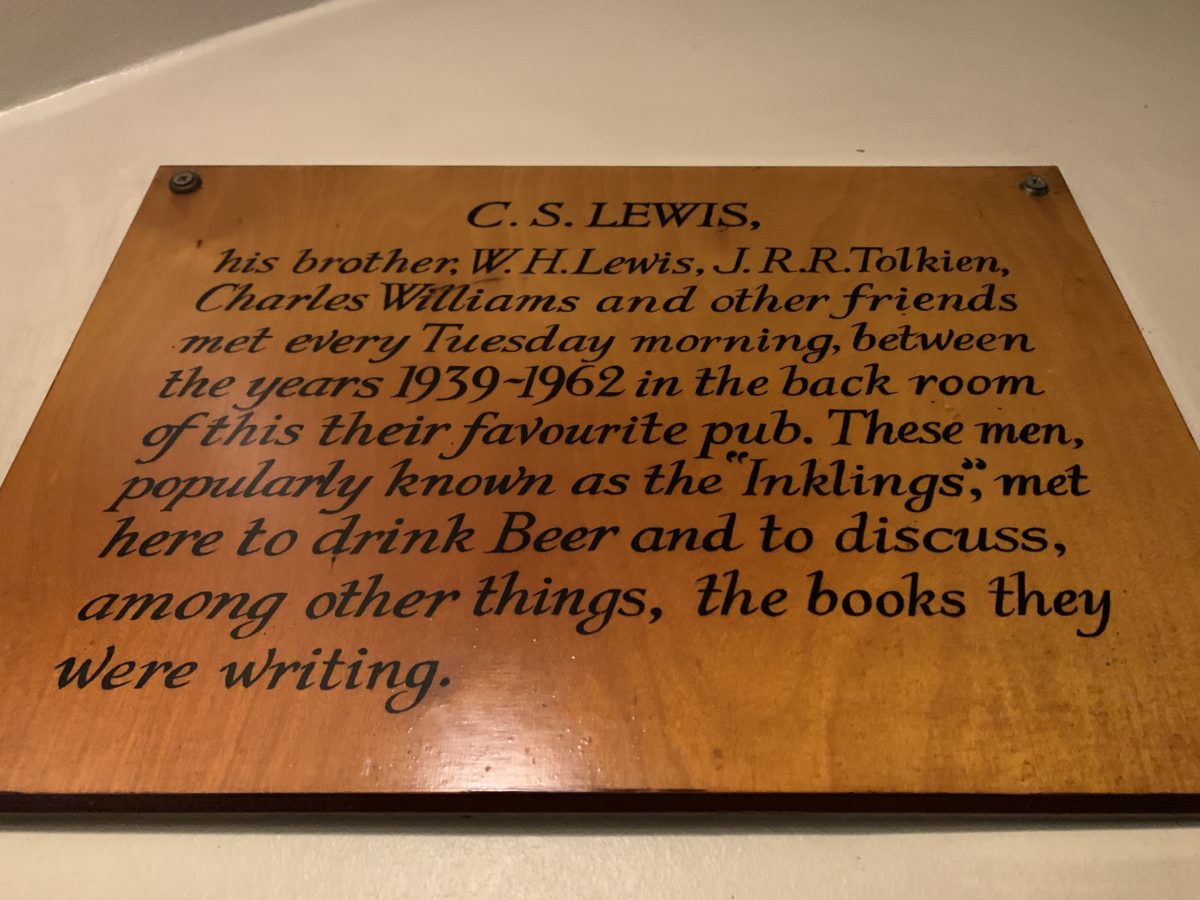

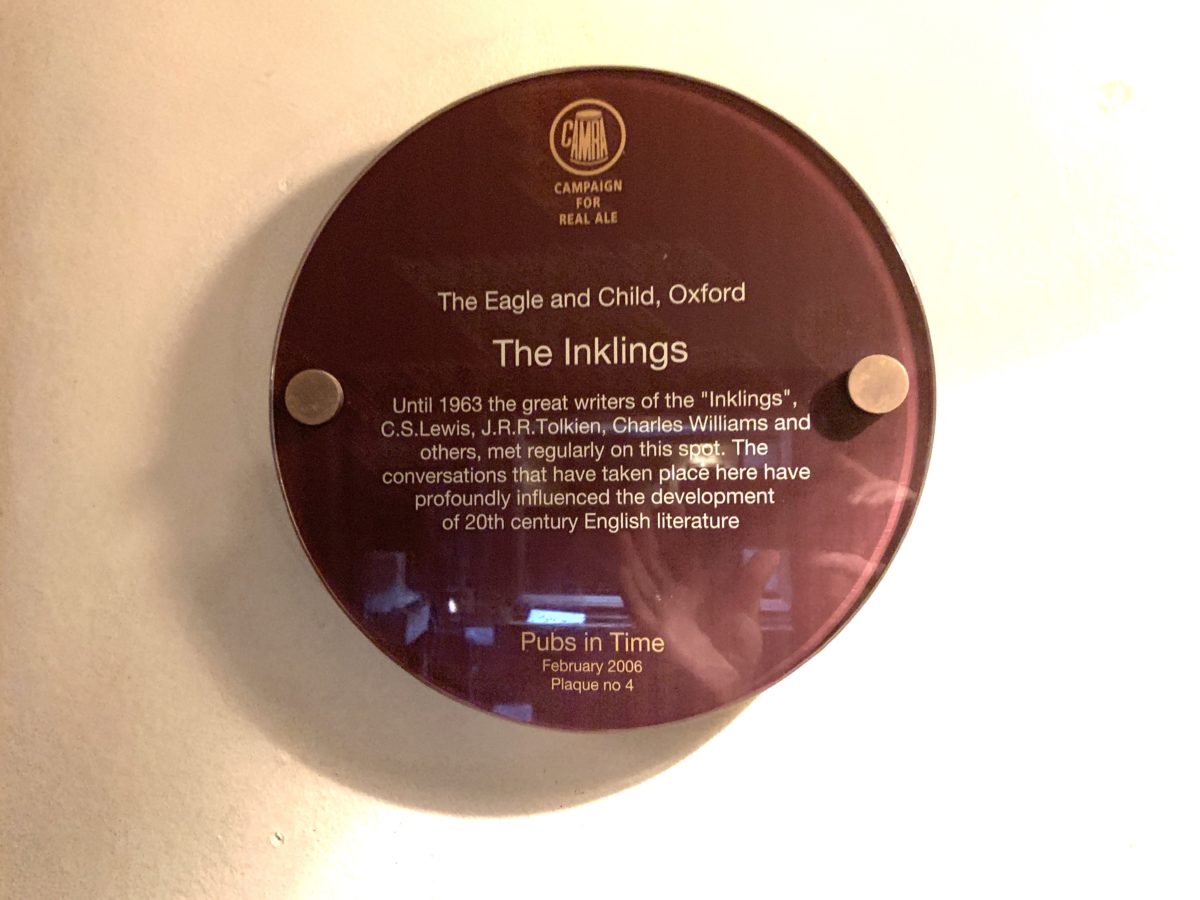

The Eagle and Child Pub (aka The Bird and Baby)

49 St Giles', Oxford OX1 3LU, UK

The famous Oxford pub where the Inklings met for beer and camaraderie throughout the 1930s and 1940s. It was also a literary incubator where they could read aloud the books they were working on. This pub is where C.S. Lewis first shared his Chronicles of Narnia and J.R.R. Tolkien his Lord of the Rings. Other famous Inklings include Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, Hugo Dyson, Nevil Coghill, Warnie Lewis (C.S. Lewis' brother), and numerous other regulars and guests.

The group met in a private lounge at the back of the pub called the Rabbit Room. The pub has since been extended, past the Rabbit Room, so the room itself is no longer private. It now sits in a sort of corridor. But it has been well preserved and contains mementos and photos of the Inklings.

We got to sit down, eat, and drink at the table in the center of the room. It's a popular tourist spot, though, so if you want to dine in the Rabbit Room, visit at off-peak times (i.e., not at prime lunch or dinner time.)

I asked the bartender how many people come to the Eagle and Child for the Inklings. He paused for a second, then said, "I'd say about 95%. We have about five or six locals who come in, but everyone else comes here for the Inklings, mostly Americans."

The famous Eagle and Child Pub, where C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and their fellow Inklings gather to share their stories and other writings.

The Trout Inn

195 Godstow Rd, Oxford OX2 8PN, UK

Another pub favored by Lewis, Tolkien, and the Inklings, which we visited for dinner with Fr. Michael Ward and Dr. Holly Ordway. It's a charming restaurant on the River Thames, which is now an "upscale, country gastropub with Thames views from a beer garden, plus roaming families of peacocks." Fr. Blake, Fr. Michael and I couldn't resist a little mischief on the river bank.

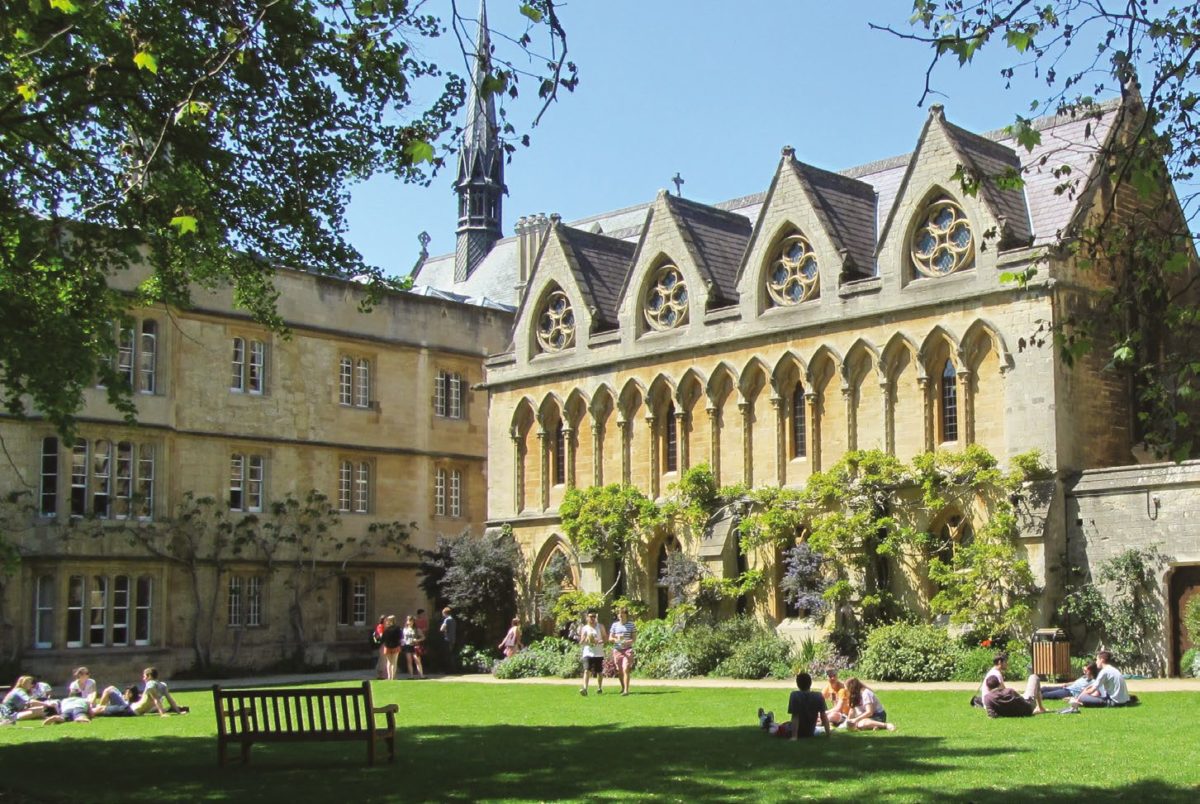

Magdalen College (Oxford University)

Magdalen College, Oxford OX1 4AU, UK

C.S. Lewis was elected tutor at Oxford's Magdalen College (pronounced "Mawd-lin") in 1925 and remained there for nearly thirty years, teaching English and writing his many books. While a professor at Magdalen, he wrote Mere Christianity, The Screwtape Letters, and all the Narnia books. It's also the place where he rediscovered his Christian faith after many years as an atheist.

Lewis had a suite of rooms in the so-called "New Building," which dates to 1735 (so much for being new—it's older than our country!) If you're looking at the front of the New Building, Lewis' rooms were on the second floor, just to the right of center.

The whole campus is simply beautiful. Magdalen is quintessential Oxford, with shooting spires, vivid greens, and even deer roaming the property.

Magdalen College Dining Hall. Unwitting tourists are known to remark, "I bet they modeled this after the Great Hall at Hogwarts!"

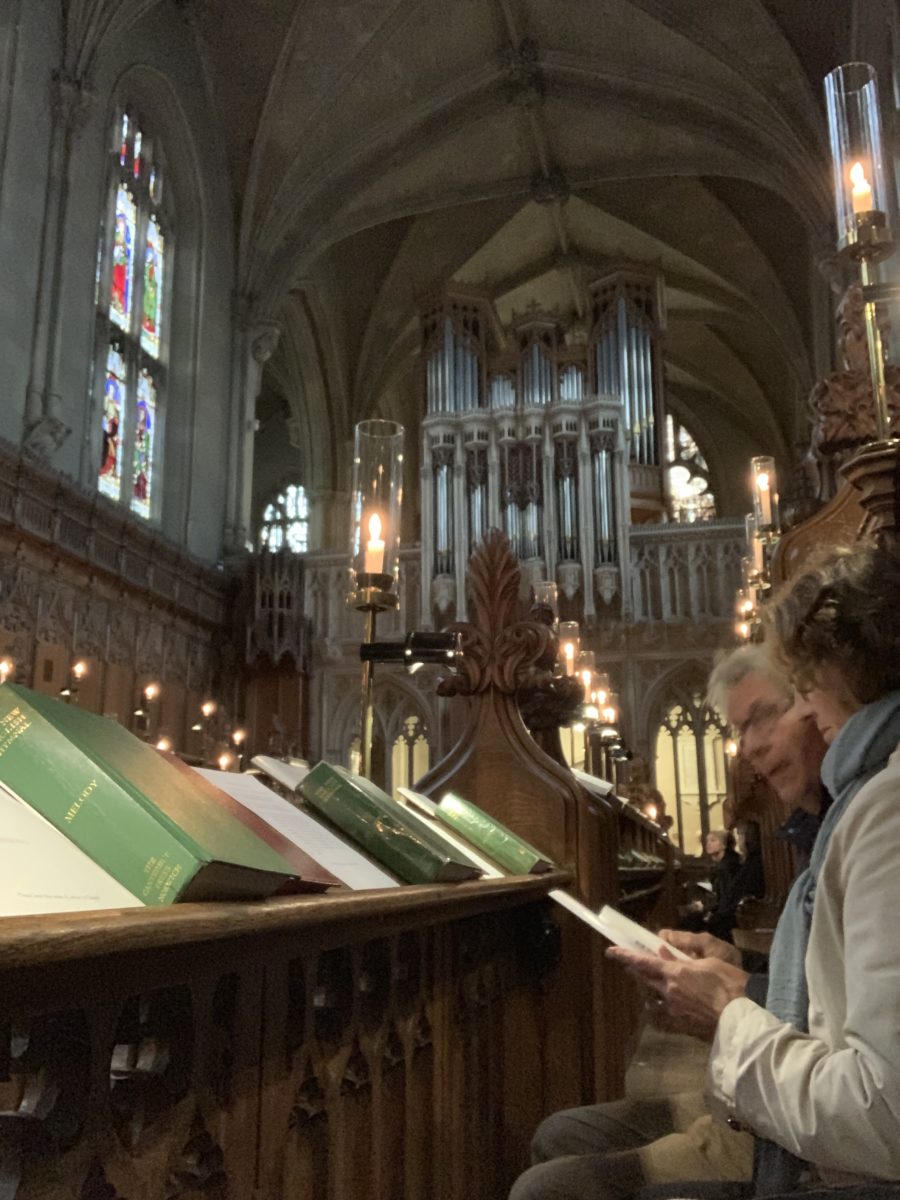

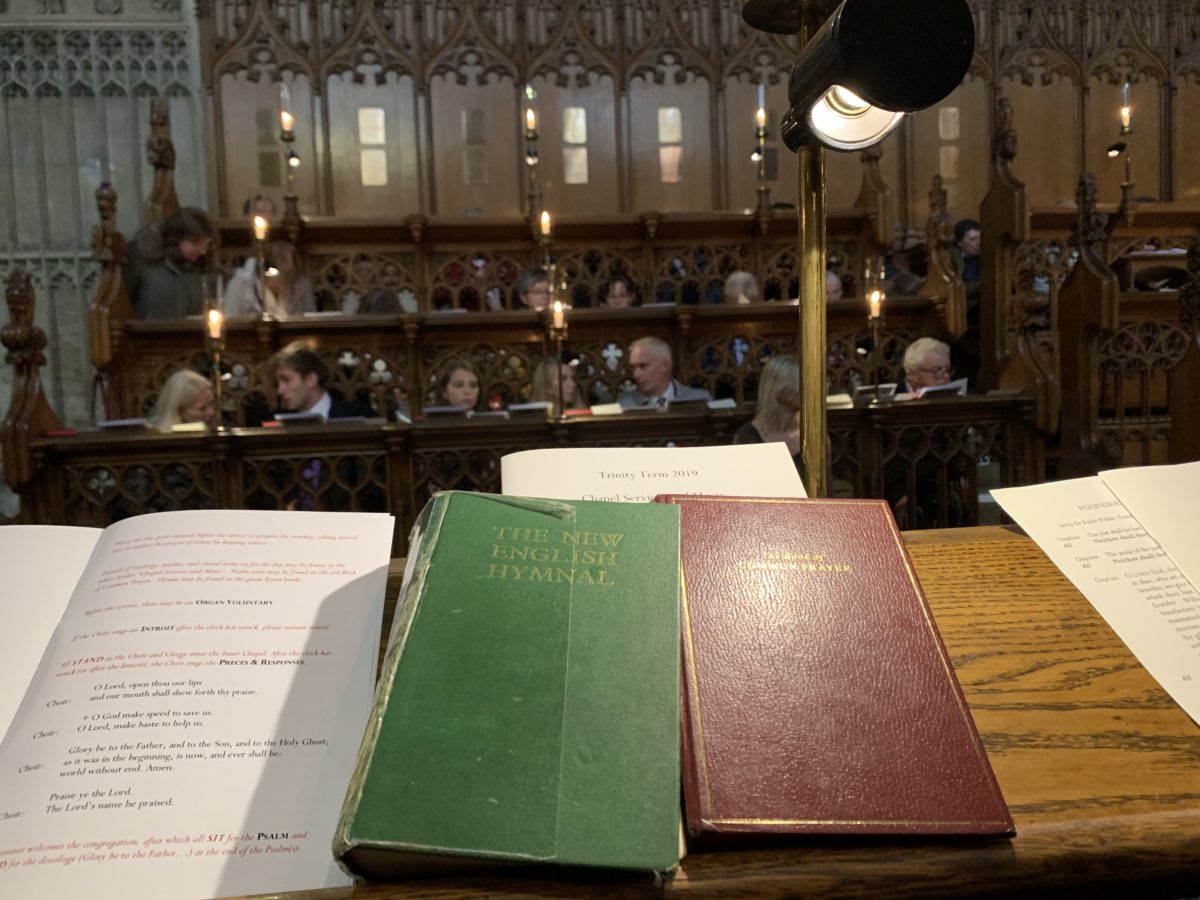

After walking the grounds of Magdalen College, Fr. Michael invited us all to Evensong in the Magdalen Chapel, where Lewis worshipped daily after becoming a Christian. Evensong is a sung Anglican prayer service, and on our visit, it featured featuring a trained all-boys choir. Imagine beautiful English hymns echoing through a stone castle, lit up by candles, and you'll get a sense for how luminous the experience was. It was just resplendent.

(Note: Evensong at Magdalen is open to the public but you have to check in and/or pay in advance, given the limited seating. But it's definitely worth experiencing!)

Addison’s Walk

Magdalen College, Oxford OX1 4AU, UK

Circling around Magdalen College, this walking path is best known as the place where C.S. Lewis first became convinced that Christianity might actually be true.

It happened on September 20, 1931. Lewis, at the time a deist, joined friends J.R.R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson, both Christians, for a walk after dinner. They ended up talking until 3am or 4am. Here's Lewis' account of the discussion:

We began on metaphor and myth—interrupted by a rush of wind which came so suddenly on the still, warm evening and sent so many leaves pattering down that we thought it was raining. We all held our breath, the other two appreciating the ecstasy of such a thing almost as you would.

We continued (in my room) on Christianity: a good long satisfying talk in which I learned a lot: then discussed the difference between love and friendship—then finally drifted back to poetry and books.

More details of that night from a letter he wrote:

Now what Dyson and Tolkien showed me was this: that if I met the idea of sacrifice in a Pagan story I didn’t mind it at all: again, that if I met the idea of a god sacrificing himself to himself . . . I liked it very much and was mysteriously moved by it: again, that the idea of the dying and reviving god (Balder, Adonis, Bacchus) similarly moved me provided I met it anywhere except in the Gospels. The reason was that in Pagan stories I was prepared to feel the myth as profound and suggestive of meanings beyond my grasp even tho’ I could not say in cold prose ‘what it meant’.

Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened.

That idea stems from G.K. Chesterton's Everlasting Man, a book Tolkien and (later) Lewis both deeply admired. The idea warmed in Lewis' mind for nine days until he finally became a convinced Christian while riding in his brother's motorcycle sidecar, on their way to the zoo. As Lewis recounts:

I know very well when, but not how, the final step was taken.

I was driven to Whipsnade one sunny morning. When we set out I did not believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, and when we reached the zoo I did.

Finally, near the end of Addison's Walk, we were led to a plaque featuring a poem C.S. Lewis wrote about the path titled "What the Bird Said Early in the Year."

Fr. Michael Ward was responsible for the getting the plaque installed, which took a lot of effort since mounting anything to any wall in Oxford faces significant hurdles. But he and his group finally received permission to put it up and were even allowed a nice inauguration ceremony.

Here's a video of Fr. Michael reciting the poem himself:

Holy Trinity Church (Lewis' Church + Grave)

46 Quarry Rd, Oxford OX3 8NU, UK

After Lewis' conversion to Christianity, he worshipped at Holy Trinity Church for the rest of his life, a charming, small parish not far from the Kilns. This is also where he is buried.

The Narnia Window, which was donated by parishioners. It features images from all seven Narnia books.

We arranged a short, guided tour with the church's verger, who showed us around. The best part was sitting in Lewis' pew, which is marked with a plaque. The pew sits adjacent to a large pillar, somewhat isolating it from the others pews. The verger explained this was because the Lewis brothers valued their privacy, especially at church, and didn't want to be bothered or approached during the service. Another reason, the verger said, is that the pulpit points directly at that pew, so its location offers a clear view of the sermon.

(I did observe that another pillar, in front of the pew, blocks any view of the altar up front. I thought it's appropriate, that Lewis, the ardent Protestant, chose to sit where he could see the pulpit perfectly but the altar not at all.)

Walking out to the graveyard, we spent time praying at Lewis' grave, where he's buried alongside his brother Warnie. As with Chesterton's grave, the experience was deeply moving.

My friend and fellow blogger Trevin Wax articulated well the experience of visiting Holy Trinity:

When you think of the scholarship and literary legacy of men like Lewis, you sometimes forget to see them as churchmen—not pastors or church leaders, but laypeople who served God’s people and worshiped alongside their neighbors. Both Lewis and Chesterton are buried in churchyards. The gift they gave the world has most benefited the church, and in the end, the churches retain their earthly remains.

Walter Hooper (C.S. Lewis' Secretary)

(private address)

During our visit with Fr. John Saward at Ss. Gregory and Augustine’s Catholic Church in Oxford (see Tolkien section below), Fr. Saward asked whether we were meeting with Walter Hooper, C.S. Lewis’ famed secretary and probably the closest person to Lewis still alive today. Hooper has edited or written introductions for approximately 30 C.S. Lewis books, and he compiled and annotated the massive, three-volume collection of Lewis' letters.

I said to Fr. Saward, “Oh, no, I mean it would, of course, be a dream to meet Walter, but I don’t have any connections and figured it wouldn’t happen on this trip.” Fr. Saward said, “Ah, well I'm sure Walter would love to meet you. Would you like me to call him?” We looked at each other and said, “Please! Yes!” Fr. Saward rung him up on the phone, Walter answered, and Fr. Saward said, “Walter! I have a few young Americans here who would like to meet you and talk about C.S. Lewis. Would they be able to come over?” It turns out Walter lives only two minutes from the parish, and just like that, we had a meeting scheduled with Walter Hooper!

I was a little worried before the visit, thinking, "This man is 88 years old. He's been answering questions about C.S. Lewis for over 50 years. Won't he be irritated by some young, American Lewis fans?" But I was told by Oxford friends who knew him that just the opposite was true. Walter loved to meet visitors, they said. The trouble was not getting him to talk—the trouble was wrapping up the conversation! They said Walter would likely try to keep us for hours and hours, preventing us from leaving, so when it was time to go we had to be forceful in our exit.

We arrived, and Walter welcomed us into his small apartment. We brought him some pecan pie since he was born in North Carolina, and we thought it would remind him of home. And from there, we spent a couple hours just sitting at his feet, listening to stories of Lewis, Tolkien, Owen Barfield, and more. It was mesmerizing.

Walter shared the hilarious story of his first encounter with Lewis, which he has told before, but with us it was as if he were telling it for the first time:

In my first meeting [with Lewis] I was almost paralyzed with both fear and admiration. Anyway, we were drinking so much tea that eventually I asked, like almost all Americans, “Do you mind if I use your bathroom?” I’d only just arrived in England and I didn’t know that in England the bathroom and the lavatory were separate rooms.

Lewis said, “Certainly not!” And he took me to his bathroom, which had nothing in it except a bathtub. He left me in the bathroom, and I was wondering what on earth I was going to do. I was really uncomfortable. For a moment, I even considered doing the vulgar act [i.e., peeing in the bathtub].

Anyway, I went back into the drawing room and I said, “Actually, it wasn’t a bath I wanted...” Well, of course he knew that. He was laughing, and said, “Ah! Now that will cure you of those American euphemisms. Let’s start over again. Where do you want to go?”

Well, it made me love him, you know? It broke the ice and I felt at ease with him and that was a very important thing for him to do. It might have backfired with somebody else, but it didn’t with me. I liked him all the more.

And as he and I walked on towards the pub, where I would get the bus back, I didn’t know whether I’d ever see him again, but I thought, I really love this man. I’d always liked his books, and I imagined I’d like him, but now I knew I did.

As we left his apartment, Walter gave us a couple books he had written on Lewis, offering to sign them for us. But as we were warned, he also tried preventing us from leaving! Even with a taxi waiting out front, he kept introducing new stories. We tried cutting him off and walking toward the door, but he got up and tried to block us, saying, "You know, I've been to Narnia! It's a real place in Italy! Want to hear about it?!" We expressed interest but said we really had to go. He was still talking to us as we gently closed the door. It could hardly have been a more charming encounter.

Oxford C.S. Lewis Society

Pusey House Oxford OX1 3LZ, United Kingdom

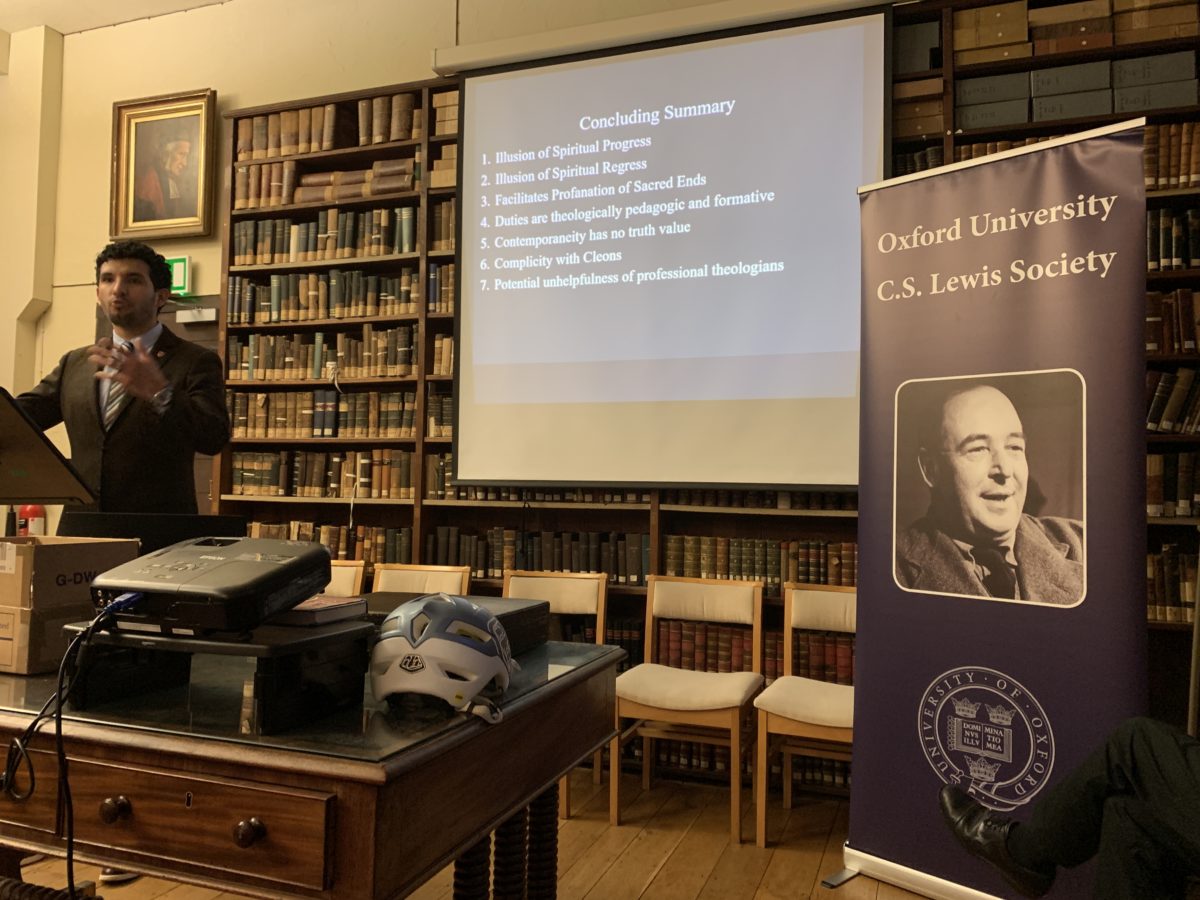

Finally, our friend and host, Fr. Michael Ward, invited us to visit the Oxford C.S.Lewis Society, which meets every Tuesday evening during term-time, usually for a talk or presentation followed by lively discussion. Fr. Michael is Senior Member [i.e. Faculty Supervisor] of the group.

We got to hear a splendid presentation from Jahdiel Perez, a young Oxford theologian and president of the Lewis Society, who spoke on “C.S. Lewis on the Perils of Professional Theology” (see his seven points in the photo below). I was encouraged to see a room full of people, young and old, students and professors, all eager to engage the thought of Lewis. Fifty years later, his influence is still alive and well at Oxford.

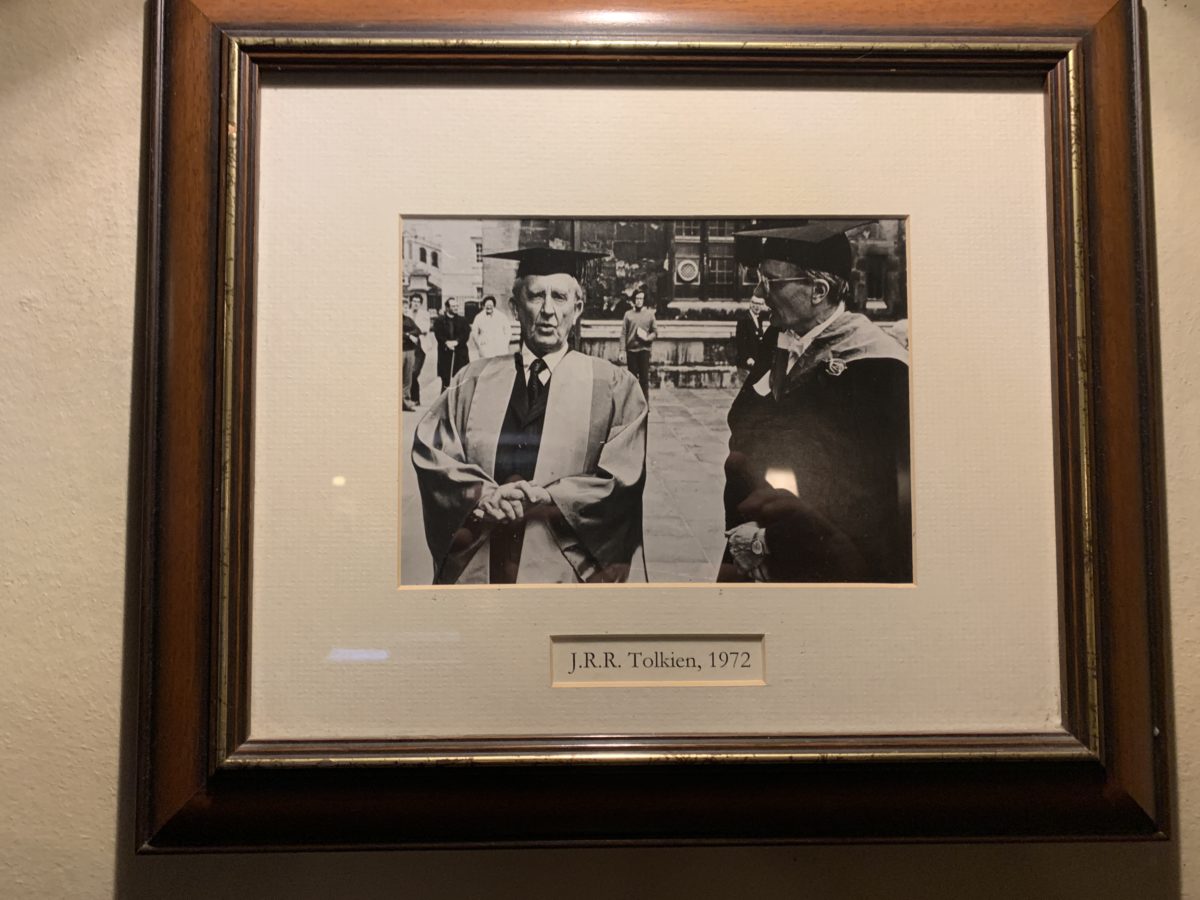

J.R.R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel (J.R.R.) Tolkien (1892–1973) was an English writer, poet, philologist, and scholar, who is best known as the author of the classic fantasy works The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion. He was also a deeply devout Catholic and, for many years, a professor of English Language and Literature at Oxford University who specialized in Anglo-Saxon literature.

Sarehole Mill

Cole Bank Rd, Birmingham B13 0BD, UK

Tolkien was born in South Africa in 1892, but after his father died in 1895, the Tolkiens moved to Sarehole Mill, a small village near Birmingham. It's where the young Tolkien spent most of his boyhood. John and his younger brother, Hilary, explored the forests and bogs, dreaming up fairy tales.

Sarehole Mill used to be a very rural area but is now all built up. They’ve restored the 18th-century working mill and added a Victorian bakehouse and a nice little Tolkien museum. If you go, be sure to visit the nearby Moseley Bog, a favorite hangout of the young Tolkien.

(Note: we weren't able to visit Sarehole Mill, but it's worth a stop, especially if you're in Birmingham, perhaps visiting the John Henry Newman sites.)

Birmingham Oratory (Oratory of St. Philip Neri)

141 Hagley Rd, Birmingham B16 8UE, UK

The Birmingham Oratory is best known as the place where John Henry Newman spent most of his life, died, and was buried (see the Newman section below).

But the Oratory also has significance for J.R.R. Tolkien fans. After Tolkien's father died, his mother, Mabel, moved him and his younger brother, Hilary, up to Birmingham. Mabel homeschooled the boys and they had a warm family life, despite grieving their fathers' death, and were supported by extended family.

But when Tolkien was 12, his mother made the surprising decision to convert to Catholicism. Her conversion was not an easy choice; it cost her greatly. Mabel’s family, nearly all Protestant, cut off support to the family, forcing the Tolkiens into poverty. Soon after, Mabel contracted diabetes and, without adequate medical care, and before the invention of insulin, she died from the disease, leaving the Tolkien boys orphans at ages 12 and 10. (John Ronald later said that "My own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants so easy a way to his great gifts as he did to Hilary and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labour and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith.")

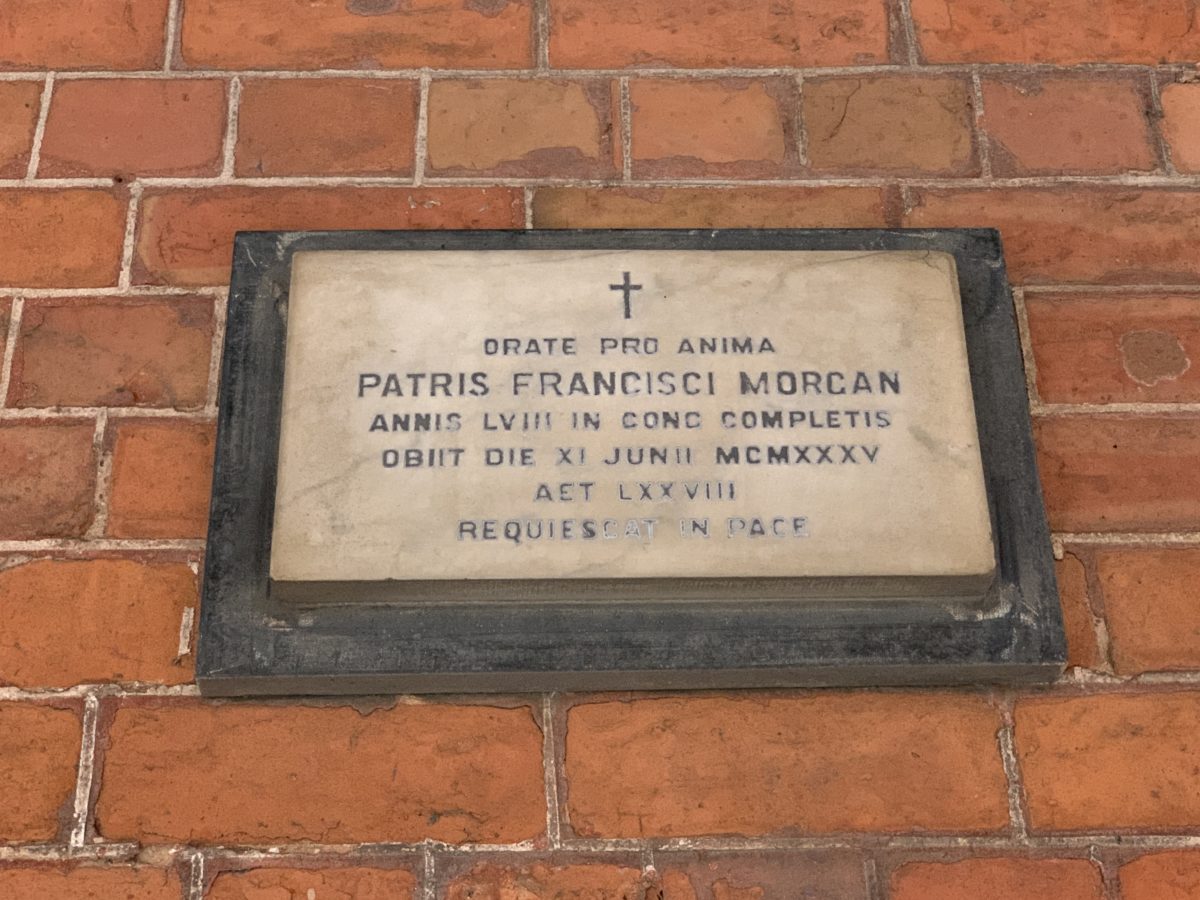

Before she died, Mabel asked Fr. Francis Morgan, a kindly priest from the nearby Birmingham Oratory, if he would serve as guardian to the two boys. He heroically took in John Ronald and Hilary and raised them, making sure they were housed, fed, and educated. He encouraged John Ronald's academic interests, helping him get into Oxford and paying all his tuition, room, and board. Next to Tolkien's mother, Fr. Francis Morgan was the most prominent influence in his life, and without him, it's likely Tolkien would not have gone to Oxford and The Lord of the Rings would not have been written.

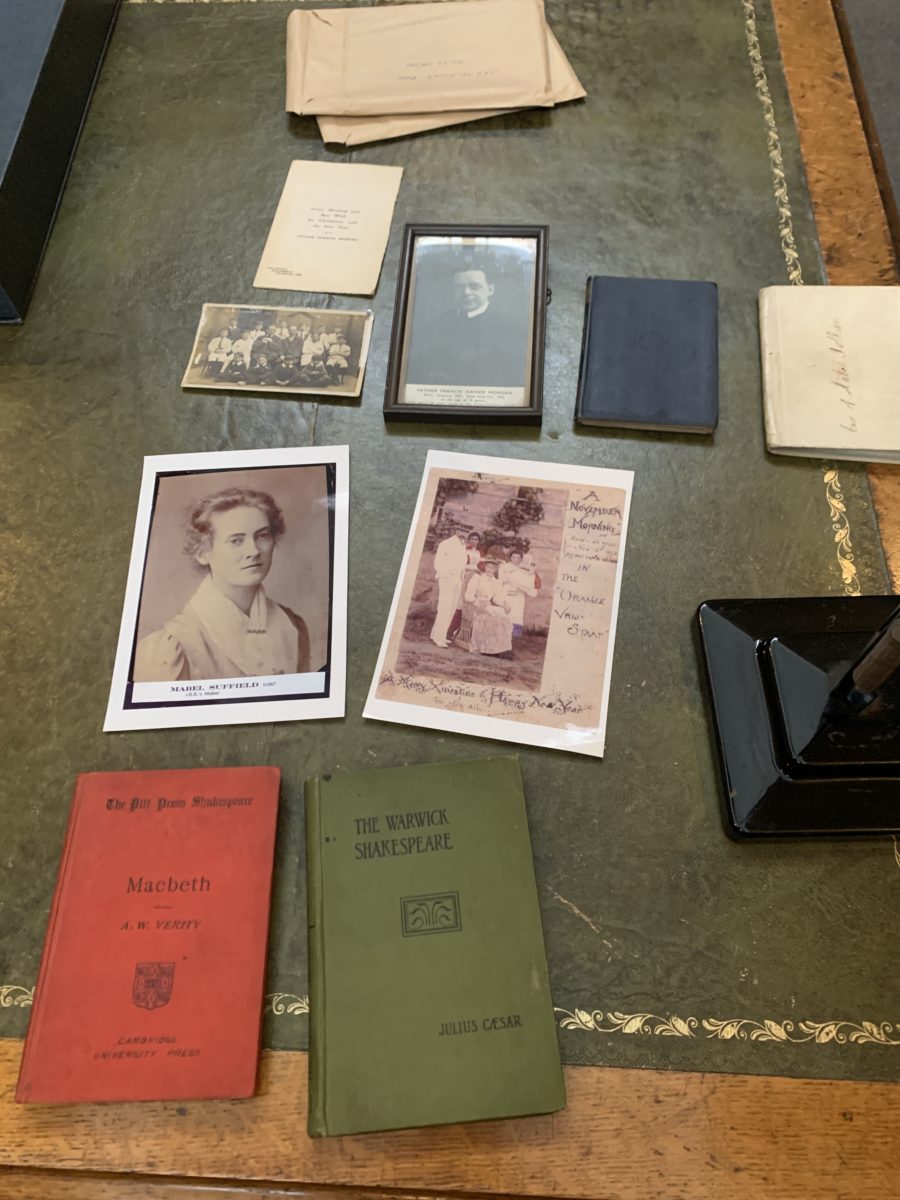

There’s much more to the story with Fr. Morgan–and the new Tolkien movie doesn’t do it justice–but what’s neat is that the Birmingham Oratory still has the Tolkien’s traveling chest, marked with a big “M. Tolkien," in which the boys carried all their worldly belongings from Africa to Birmingham. You can also see some of Tolkien’s boyhood schoolbooks, including two Shakespeare texts that Tolkien marked up as a young student.

J.R.R. Tolkien memorabilia at the Birmingham Oratory. The priest pictured is Fr. Francis Morgan, and the two pictures in the middle are of his mother and family. The two books at the bottom are his boyhood Shakespeare books, which Tolkien marked up.

J.R.R. Tolkien's Home #1

20 Northmoor Rd, Oxford OX2 6UR, UK

Tolkien lived here from 1926 until 1947, and it’s where he wrote most of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. We didn’t visit this house, since it's privately owned and you can’t get too close to it. But if you’re in the area, and you're a Tolkien devotee, it might be worth stopping by.

J.R.R. Tolkien's Home #2

76 Sandfield Rd, Oxford, OX3 7RL, UK

The Tolkiens lived here from 1953 to 1968, towards the end of their time in Oxford. All three volumes of The Lord of the Rings were published (though not written) while he lived in this house. We didn’t visit here either. Like the first house, this is privately owned and you can’t get close. I don't believe there’s a historical marker on it, either.

Ss. Gregory and Augustine’s Catholic Church

322 Woodstock Rd, Oxford OX2 7NS, UK

This is the church where J.R.R. Tolkien and his family worshipped. They attended Mass here regularly, always sitting in the front right pew.

Fr. Blake, my wife, and I showed up for a normal, Tuesday morning Mass. Only a handful of people dotted the pews but the pastor, Fr. John Saward, offered a beautiful ad orientem, Novus Ordo liturgy with careful reverence and precision. There was no music or homily but it was still one of the most exquisite Masses I’ve experienced.

I reflected during prayer how this small little church, and the Blessed Sacrament resting at its center, inspired so much of the ethos behind Tolkien's Middle-earth. As Tolkien said, The Lord of the Rings "is of course a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision."

Tolkien sat in these pews, gazing at this altar, with thoughts like these swirling in his mind:

Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament. . . . There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves on earth, and more than that: Death. . . . The only cure for sagging or fainting faith is Communion.

We learned afterword that sitting in the pew next to us, during Mass, was Priscilla Tolkien, J.R.R. Tolkien’s daughter and one of just two Tolkien children still alive. She's 90 years old but still attends daily Mass there, though we were told she emphatically does not like to be asked about her famous father.

But there was another treat after Mass. We got to spend time with Fr. Saward, the pastor of the church, who has long been one of my favorite writers. He's among the greatest spiritual masters in England. I’ve enjoyed his books for many years, especially The Way of the Lamb, The Beauty of Holiness and the Holiness of Beauty, and Firmly I Believe and Truly. His prose is elegant and witty, very much in the tradition of Newman, Chesterton, and Knox. He's also deeply alert to matters of the soul.

After Mass, Fr. Saward invited us back to his study for tea and we chatted for nearly an hour, discussing many of the writers he had studied, including Chesterton, Thérèse of Lisieux, Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI), and Hans Urs von Balthasar.

We were surprised (and impressed) to learn Fr. Saward had translated many of our favorite Catholic books into English, including Ratzinger’s Spirit of the Liturgy and volumes from von Balthasar’s The Glory of the Lord series. In fact, he had met von Balthasar several times and attended retreats with him. Our conversation in his study was wonderfully rich and rangy.

Upon leaving, we all remarked how impressed we were that this world-class theologian and spiritual writer quietly said Mass here, morning after morning, for a handful of parishioners in this small English church, serving his parish with deep devotion and reverence, regardless of its size or significance. It was a powerful witness of a pastor-scholar, a priest-theologian, and precisely what the Church needs right now.

Exeter College

Turl St, Oxford OX1 3DP, UK

This is where Tolkien studied as a student at Oxford. We didn’t visit Exeter, but it might be worth a tour. Before you do, though, read John Garth's short booklet, Tolkien at Exeter College, which has lots of interesting details about Tolkien's time there.

Tolkien’s Grave

447 Banbury Rd, Oxford OX2 8EE, UK

J.R.R. Tolkien and his wife, Edith, are buried here. What’s especially notable is the inscription on the gravestone, which reads “Edith Mary Tolkien - Lúthien - 1889-1971” and “John Ronald Reuel Tolkin - Beren - 1892-1973”.

J.R.R. Tolkien's grave. The tombstone reads: "Edith Mary Tolkien - Luthien - 1889-1971" and "John Ronald Reuel Tolkien - Beren - 1892-1973".

Beren and Lúthien are key figures in Tolkien’s Silmarillion. (Warning: spoilers ahead if you haven't read the book.) Beren was a mortal man who fell in love with Lúthien, an immortal elf. Her father, a great elvish lord, opposed the union and would only allow them to marry if Beren performed an impossible task: steal a Silmaril, a special jewel, from the greatest of all evil beings, Melkor.

Beren succeeded in stealing the jewel, but he died in the attempt. Luthien then died, too, while grieving for Beren, and once in the underworld, she despaired of ever seeing Beren again since he was a mortal man. But Mandos, Ruler of the Dead, was moved to pity, and offered Lúthien a choice: she could remain immortal and live in the underworld without Beren, or Mandos could return both of them to their life in Middle-earth, though as mortal creatures, bound to die the death of mortal men. She chose the latter fate, sacrificing her immortality to be with Beren.

“I never called Edith Luthien,” Tolkien wrote to his son Christopher in 1972, a year after Edith’s death, “but she was the source of the story that in time became the chief part of the Silmarillion.”

There are many links between Tolkien/Edith and Beren/Luthien. Like the two Silmarillion characters, Tolkien and Edith faced resistance as young lovers. And like Luthien, Edith had to sacrifice much to be with Tolkien, including a jilted fiancé, her home, and her religion (Edit converted to Catholicism to marry Tolkien.) Learn more about the many connections between Tolkien/Edith and Beren/Luthien in this article.

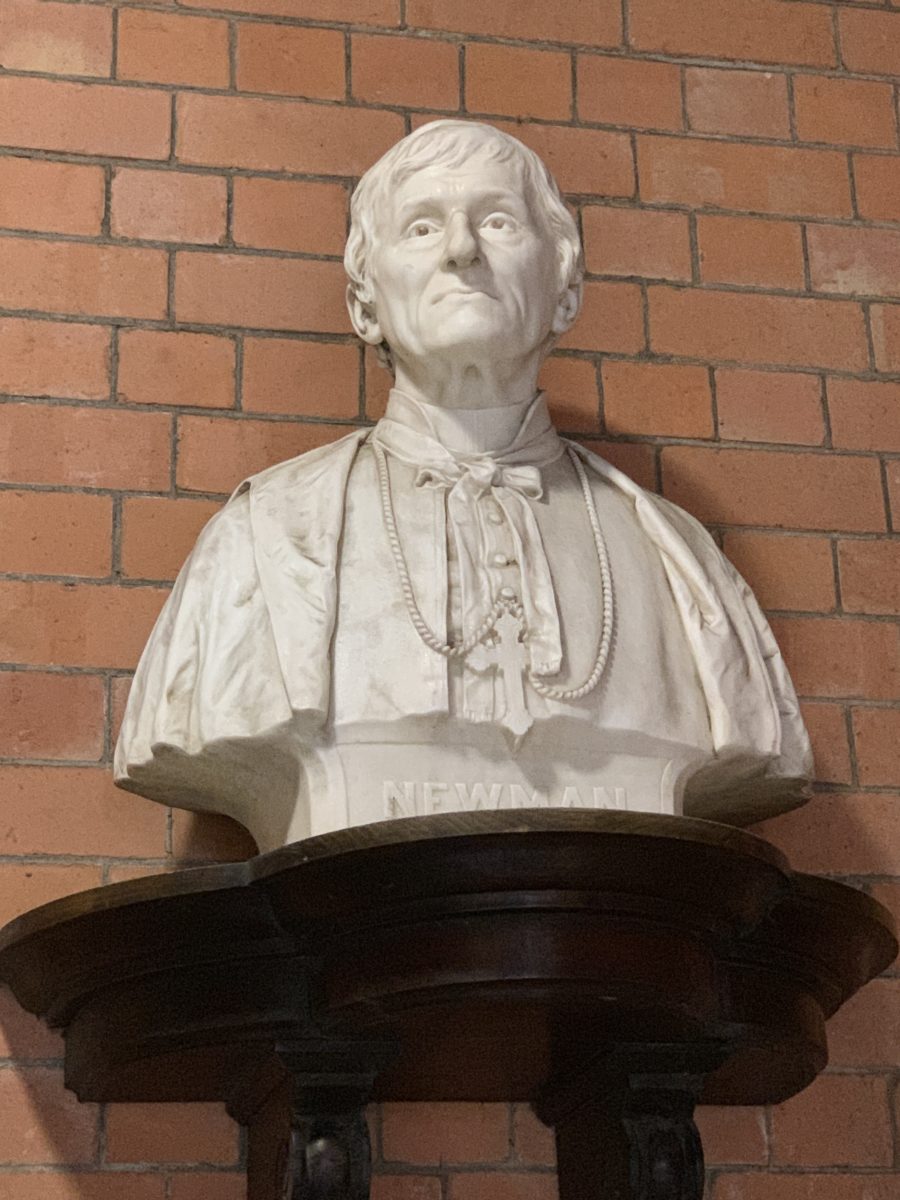

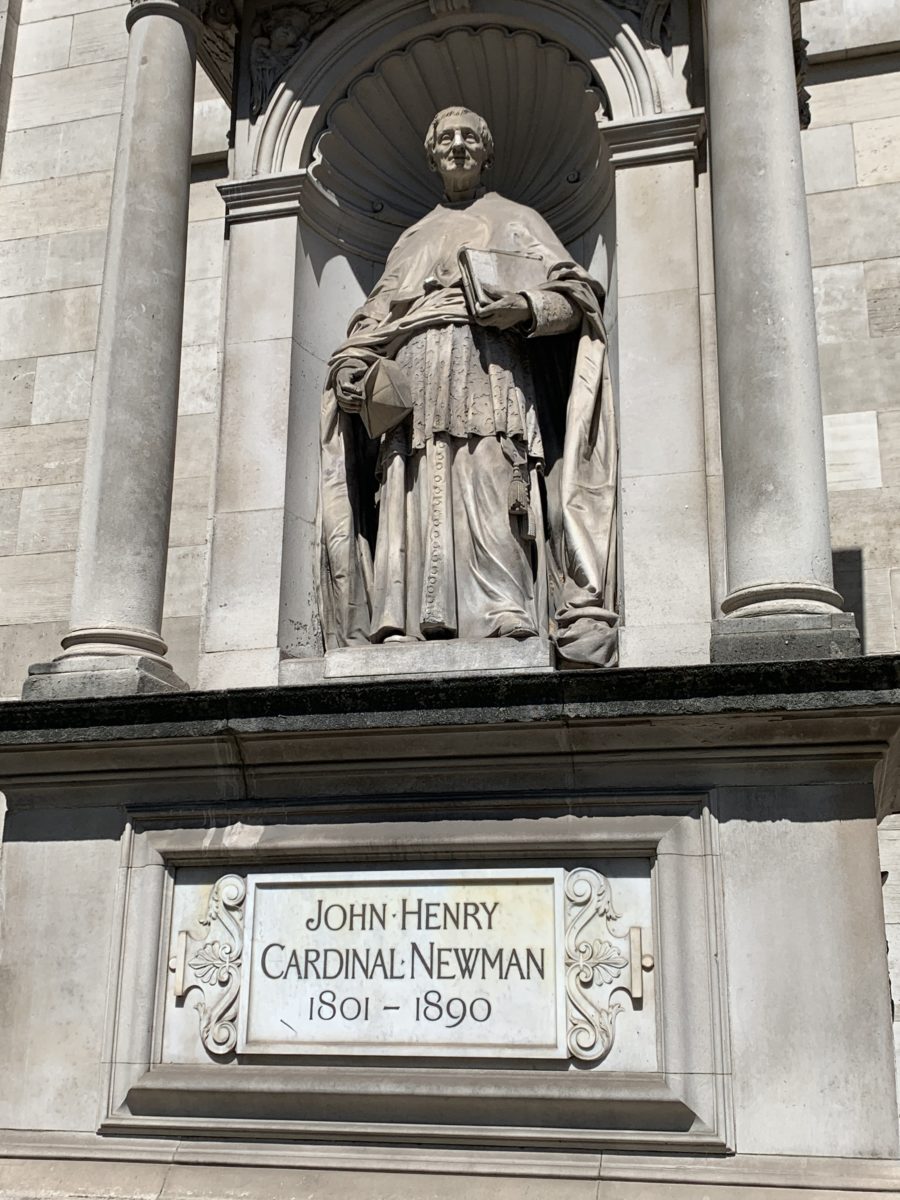

John HENRY NEWMAN

John Henry Newman (1801-1890) was a priest, theologian, poet, and perhaps the most famous convert from Anglicanism to Catholicism. He's the author of many classic religious texts such as the Apologia Pro Vita Sua, his intellectual conversion memoir, Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, and The Idea of a University.

Pope Benedict, himself a devotee, beatified Newman in 2008, and later this year, on October 13, 2019, Pope Francis will canonize Newman, formally recognizing him as a saint of the Catholic Church.

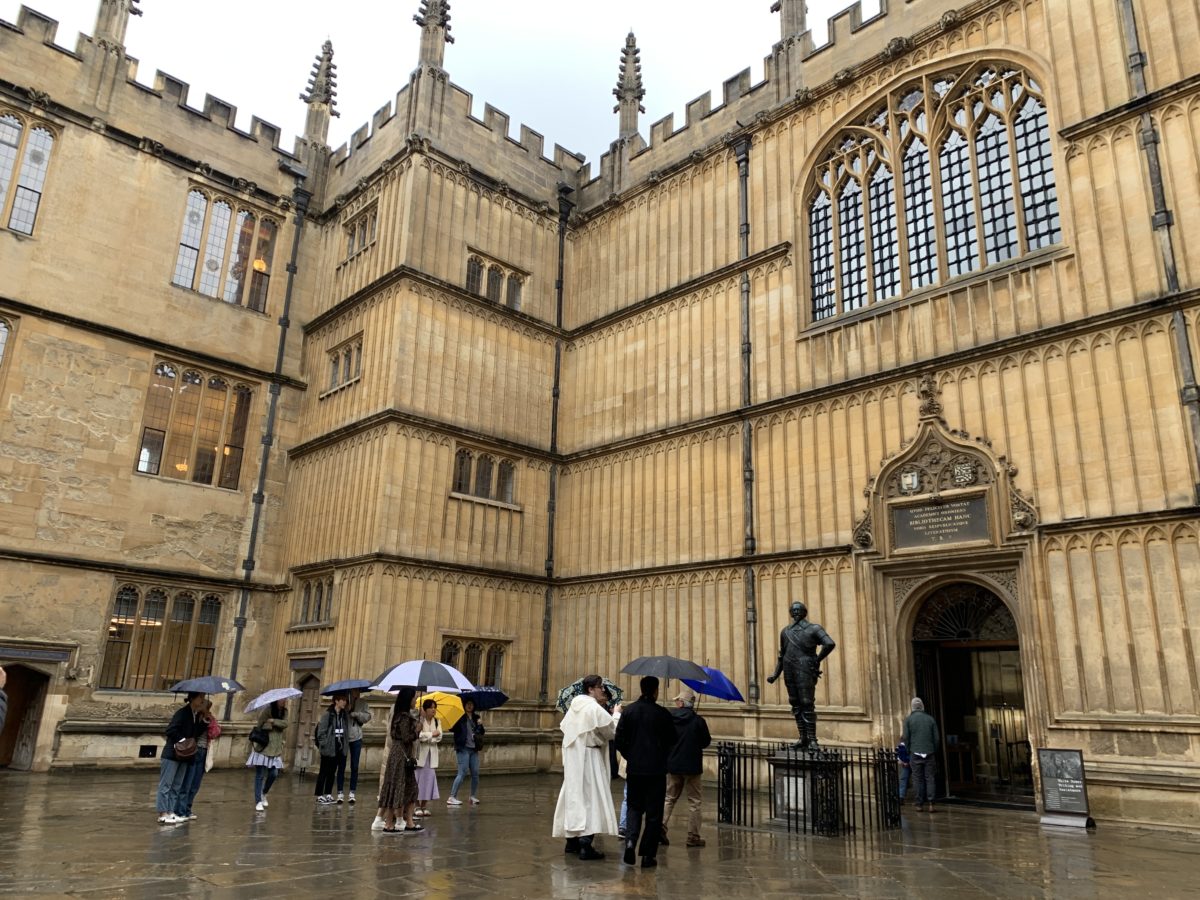

University Church of St Mary the Virgin

High St, Oxford OX1 4BJ, United Kingdom

As an Anglican priest, John Henry Newman served as Vicar of this church for fifteen years, between 1828-1843, until he decided to leave the Anglican Church. Two years later, in 1845, he converted to Catholicism. You can walk into University Church today and see the pulpit from which Newman preached many of his sermons.

Pulpit where John Henry Newman used to preach as an Anglican chaplain. It was also from this pulpit where C.S. Lewis delivered perhaps the most famous sermon of the twentieth century, titled "The Weight of Glory".

Oriel College

Oxford OX1 4EW, UK

In 1824, after finishing his undergraduate studies at Trinity College, Oxford, Newman was elected to a fellowship at Oriel. He taught there for many years and later served as Chaplain of Oriel from 1826-1831, then again from 1833-1835.

We didn't have much time to explore Oriel, and much of it was closed, but we were able to sneak up to the special prayer nook behind the organ in the main church. This is where Newman spent much time in private prayer during his difficult final years as an Anglican.

Littlemore

9 College Ln, Oxford OX4 4LQ, UK

In 1842, once Newman became convinced he could no longer remain Anglican, he and a small group of friends withdrew to The College at Littlemore.

The small residence offered a semi-monastic life, away from the busy, high society at Oxford, a place of prayer and study where Newman and his friends could discern where God was leading them.

It was here, in 1845, where Newman wrote his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, and toward the end of that work, it became clear that he must seek admission into the Roman Catholic Church. He was soon received into the Church right here, at Littlemore.

Littlemore was eventually acquired by the Birmingham Oratory and is now run by a group of religious sisters from The Spiritual Family The Work (FSO).

During our visit, the sisters allowed us to celebrate Mass in Newman's private oratory, the place where he spent so much time in search of the truth, where he prayed and celebrated Mass each day. It was joy to celebrate Mass with two of my dearest priest-friends: Fr. Michael Ward, a recent convert from Anglicanism to Catholicism via the Personal Ordinariate, and Fr. Blake Britton, a priest in the Diocese of Orlando.

Worshipping there alongside my wife and another friend, Dr. Holly Ordway, was quite special. You couldn't help but feel connected to the small band of searching, aspiring converts, kneeling and praying in the same place nearly two hundreds years before, wondering what their future held.

While at Littlemore, we also toured Newman's private room and library. The library is the site of Newman's reception into the Catholic Church. On October 9, 1845, Fr. Dominic Barberi heard Newman’s confession and received him into the Church in front of the fireplace.

The famous fireplace where John Henry Newman was received into the Catholic Church. This fireplace is, quite obviously, a replica, but this is the precise site of what was perhaps the most famous Catholic conversion of the nineteenth century.

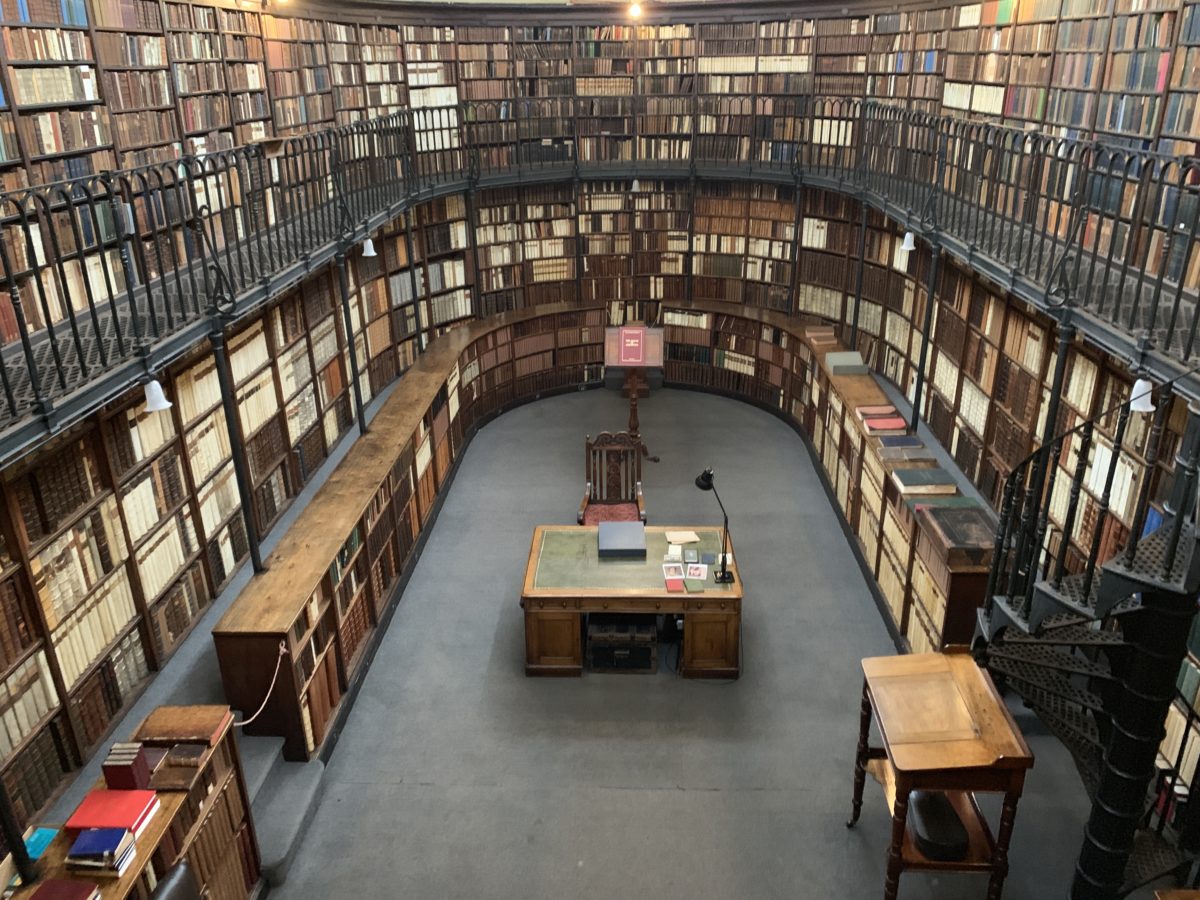

The Littelmore library includes an exhibition of Newman memorabilia (prints, etchings, photographs, sculptures, and original letters). I was most excited to see and touch Newman's standing desk, where he wrote the aforementioned Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine.

The desk where John Henry Newman composed his "Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine." Newman had a standing desk before standing desks were cool.

If you're at all interested in Newman, Littlemore is a wonderful stop. The spaces are small and intimate, and all of them are open to visitors—Newman's room, chapel, and library. You can even stay in one of the five guest rooms, where Newman's friends lived, and follow their rhythm of prayer, reciting the Divine Office and celebrating Mass. Before your visit, check the website in advance for times.

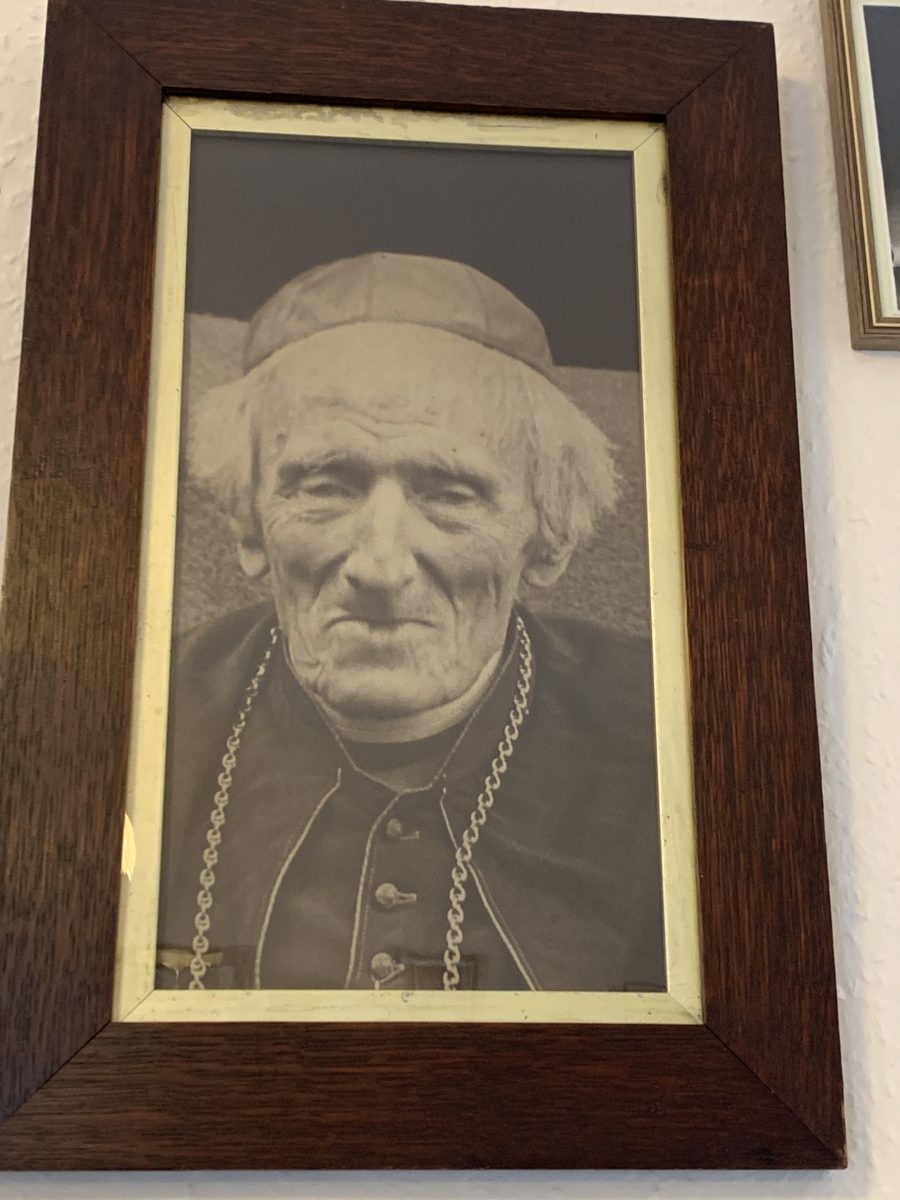

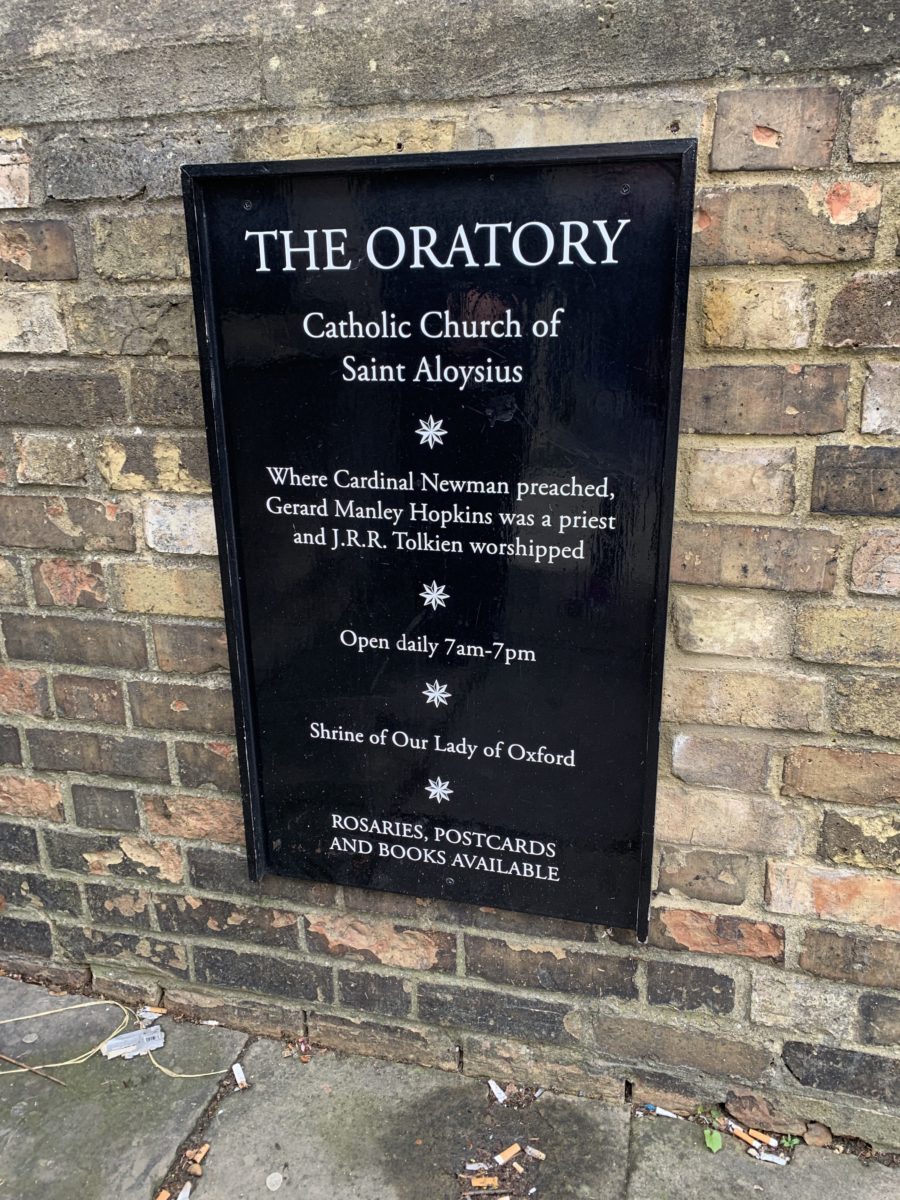

Oxford Oratory (Catholic Church of St. Aloysius Gonzaga)

25 Woodstock Rd, Oxford OX2 6HA, UK

This beautiful Gothic church was originally built in 1875 as the Jesuit parish of central Oxford. Just over a century later, in 1980, the Jesuits gave the church to the Archdiocese of Birmingham, which invited members of the Birmingham Oratory (the community started by Newman, see below) to take it over and found a new Oratorian community in Oxford.

The church been described as the place "where Cardinal Newman preached, Gerard Manley Hopkins was a priest, and J.R.R. Tolkien worshipped."

Birmingham Oratory (Oratory of St. Philip Neri)

141 Hagley Rd, Birmingham B16 8UE, UK

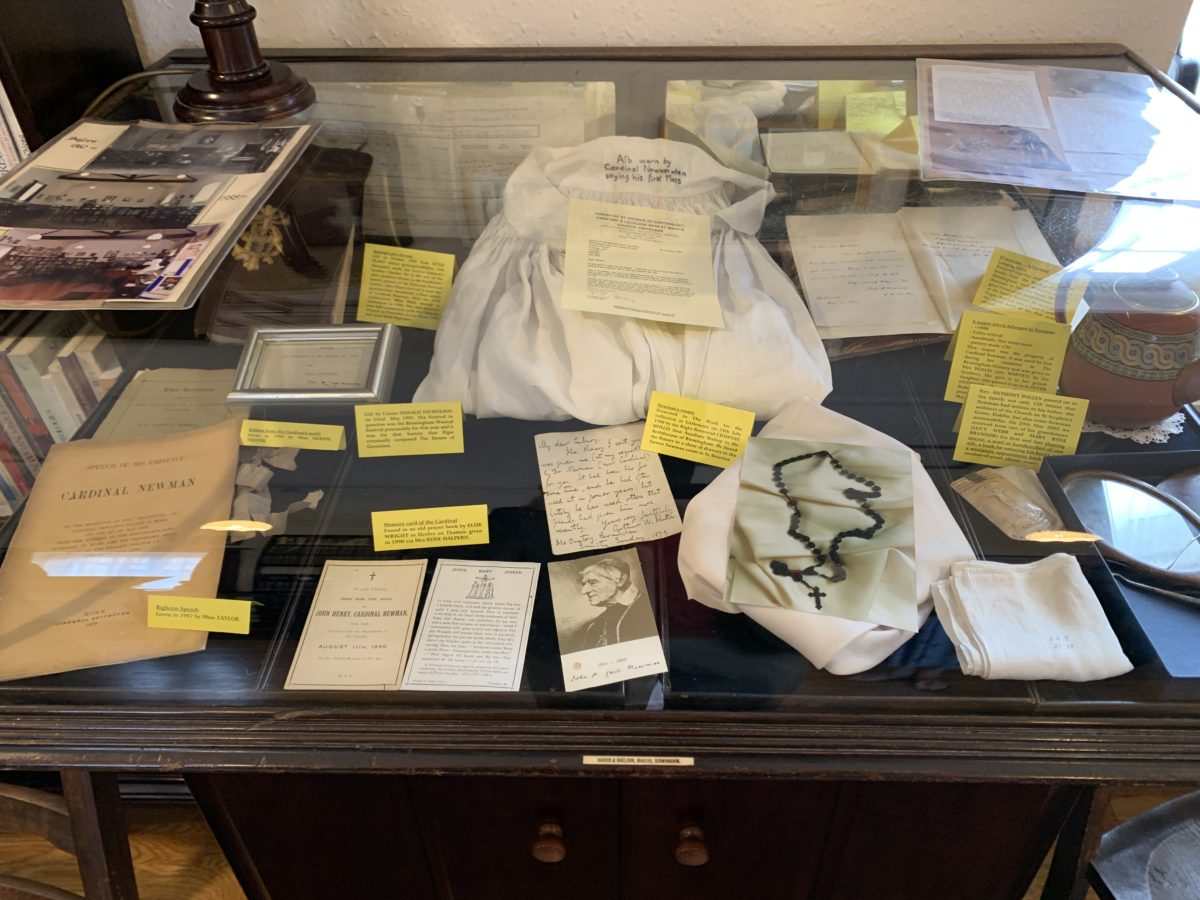

The Birmingham Oratory is the site most associated with Newman. He founded this Oratory in 1847, and lived here from 1852 until his death in 1890. He was buried in the nearby cemetery, though nothing of him remains there now (more on that below.)

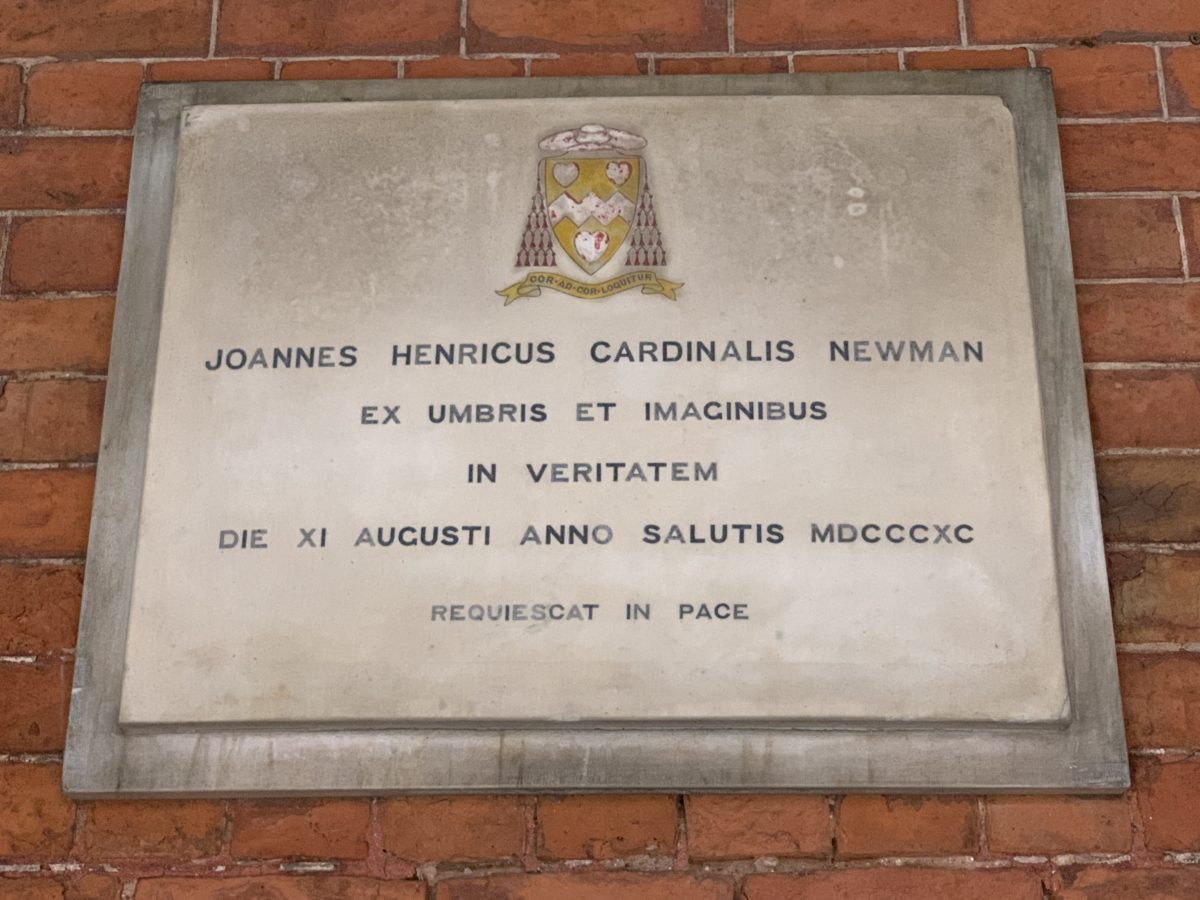

Plaque placed in the Oratory cloister after Newman died. His body was exhumed in 2008 as part of his beatification proceedings, so there is no longer a grave site to visit.

Unfortunately, Newman's private room and chapel at the Oratory are off limits, even to private tours, because nearly everything inside is deteriorating. But we did have access to their beautiful Newman shrine, which is being renovated for his upcoming canonization on October 13, 2019. Right now, the shrine is only available for private tours but will soon be permanently open to the pubic.

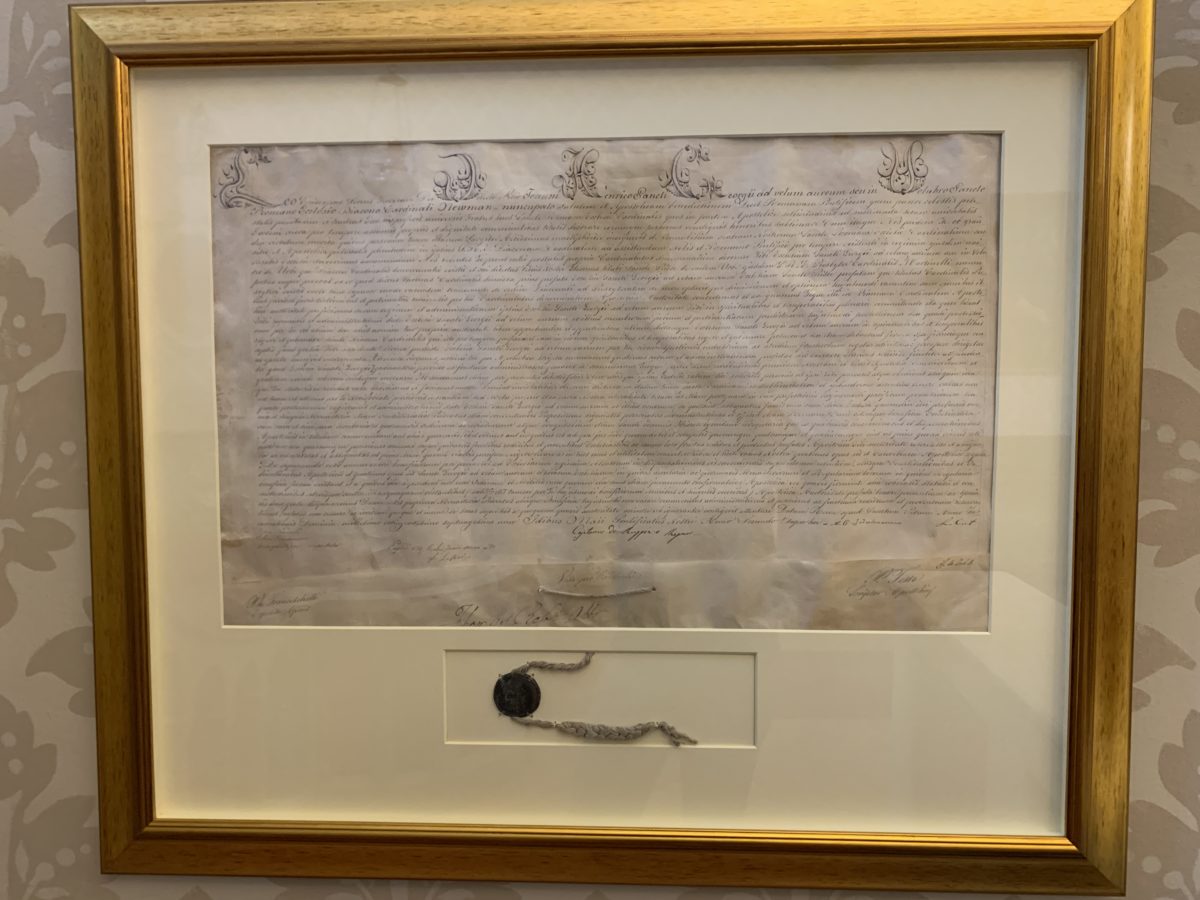

The shrine has several interesting items. First, are the only first-class Newman relics in existence. These include a few hairs from Newman, which I believe were clipped before his death, and one tiny bone fragment. When they dug up Newman’s body for the beatification proceedings in 2008, they found that virtually everything—Newman’s bones, the wooden casket, and the surrounding mould—had all dissolved into dust. There was just nothing left, with the exception of this tiny bone fragment, smaller than a penny. It seems this was actually Newman’s intention. He chose a wooden casket and poor burial materials on purpose, knowing that the moist Birmingham soil would quickly decompose everything. It was his preference that his body would just fade back into the earth.