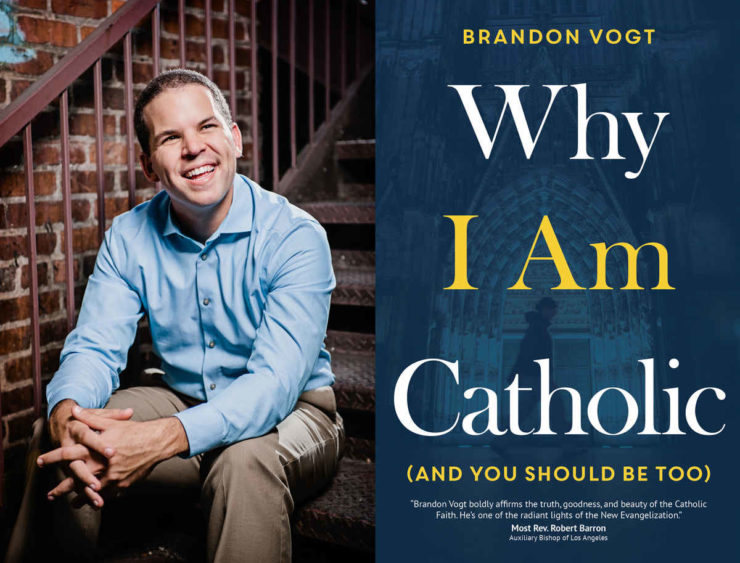

A couple exciting items about my new book, Why I Am Catholic (And You Should Be Too).

First, the book recently earned a 1st Place Award from the Catholic Press Association for being this year’s best “Popular Presentation of the Catholic Faith.” So exciting!

Second, I was recently interviewed about the book by Angelus News, the newspaper for the Archdiocese of Los Angeles. The reporter sent me several questions via email but, due to space, was only able to quote a few lines for the final piece.

I asked if I could just share the full interview here on my blog, and he said yes. So here you go! Read below for some great discussion about God, atheism, science, sex, the abuse crisis, and more.

QUESTION: Why did you think it was important to write this book, and how has your work as an evangelist shaped the way you wrote it?

BRANDON: The main reason I wrote the book is because I’m convinced the number one problem in the Catholic Church today is the massive amount of young people drifting away. The latest Pew religious landscape survey found that for every one person becoming Catholic, more than six leave. Half of Millennials who were baptized in the Church no longer as identify as Catholic today. These are harrowing stats, but they especially hurt because, as a Millennial convert, I discovered many good reasons to become Catholic, reasons that apparently haven’t reached or convinced my peers. So that’s why I wrote the book: to make a compelling case to young skeptics and former Catholics about why they should consider Catholicism.

My work over the years has definitely shaped the book. For the last five years I’ve run StrangeNotions.com, a site which brings together Catholics and atheists to discuss the Big Questions of life. A lot of those discussions shaped the arguments and approach in my book. I’ve also worked for nearly five years with Bishop Robert Barron, arguably the greatest evangelist in the English-speaking world, and I’ve learned so much from him. His fingerprints are all over the book, too.

QUESTION: In your section about why you believe God exists, you restate a number of classical arguments for God’s existence. I’m curious, one argument (and I’m a believer, by the way) I didn’t quite buy was the moral argument—it seems to me one can make a case for morality based solely on the need for collective safety, i.e., since we’re all living together, it’s a bad idea if any of us murders others. While I personally believe God inspires us to be moral, I also believe morality, aside from God, stands on its own—we all have a vested interest in a civil society. How would you respond?

BRANDON: I’d say this explanation may sound good on the surface, but it falls apart as soon as you press it a little. For example, it presumes that safety (or survival, or maintaining a civil society) is the ultimate ground for morality, that an act is moral because it leads to the greatest amount of happiness or survival for the largest number of people. This is known as utilitarianism, and while it’s popular today, it’s also problematic. The main issue is determining what qualifies as the greatest good. You may choose one variable (e.g., collective safety) and make it the prevailing standard. But what about others who disagree and think, for example, that the greatest good necessitates purging sick people or people they deem racially inferior, since that’s really best for collective society? What objective criteria determines the “greater good”? There doesn’t seem to be any. Thus, this view is ultimately subjective; it trades in opinions and personal beliefs, not objective truth.

Another issue with this utilitarian approach is that it sometimes leads to immoral results. For instance, suppose someone is sick with a contagion. There’s little question that society would be happier and safer if that person was killed. Is it thus OK to murder that sick but innocent person? Most of us would say no. But if that’s the case, there must be some other, more foundational moral framework besides maximizing collective safety or happiness, some moral grounding that affirms an act as wrong, even when it seems to improve collective happiness or safety.

So if we agree, as most people do, that morality must have an objective basis, meaning a standard that transcends mere human preference or personal desire, it can’t come from democratic consensus, biology, or evolution. All of those are contingent or subjective. God seems to be the only fit.

QUESTION: You also seem to allude to the Intelligent Design argument without specifically referencing it, by noting the mathematical elegance of creation, among other aspects. Would you consider yourself a believer in ID or is your view more nuanced than that?

BRANDON: Just to be clear, I don’t endorse Intelligent Design as it’s typically understood, meaning an argument for God based on the irreducible complexity in creation (e.g., the eye is so complex, only God could have designed it.) I don’t find those arguments compelling, and that’s not what I propose in my book.

In Why I Am Catholic, I take a different approach, arguing that the intelligibility of the world (not intelligent design) is a clue that it came from a supreme intelligence. That the world is marked by order, patterns, and rationality is actually surprising. It’s strange and unexpected. Our universe certainly didn’t have to be that way, as scientists have observed. If our universe arose by chance, a disorderedly chaos would have the been far more likely outcome. But the universe we experience is coherent and predictable. We can wrap our minds around larges parts of it. It can be described and mapped through laws and equations. This surprising order, I argue in the book, demands an explanation, and as I suggest in my book, the Christian explanation makes far more sense of it than any alternative.

QUESTION: You readily acknowledge marginalized folks, i.e. gays, have a lot of trouble these days understanding why anyone would want to be Catholic. One thing that has struck me over the years is that it’s easy for married heterosexuals to call others to a life of celibacy, specifically gay people, but I’m curious have you ever explored the idea the church may someday embrace married gay couples? I was a Catholic journalist from 1988 on and have heard many different viewpoints on this issue, so I’m not sure the church will always teach that same-sex individuals must refrain from having sex.

BRANDON: The problem with trying to answer this is that we need to define our terms. What do we mean by “embrace”? If by that we mean the Church welcoming them into her fold, loving same-sex attracted men and women, championing their dignity, and inviting them into a full and flourishing relationship with God, then unequivocally yes: the Church embraces them just as it embraces every human being.

But if by “embrace” we mean endorse or affirm the attempt to marry someone of the same sex, then the answer is certainly no. The Church will never do that. The Catholic Church is convinced, via the teachings of Jesus and the reasoning of natural law, that marriage is an institution which unites men and women to each other and to any children they produce. That’s what marriage is. And that union is sealed by the sexual act. Sex is what completes (or consummates) a marriage, because that very act does what marriage exists to do: it joins the couple in a comprehensive union, one which is open to generating new life.

This why the Church rejects sex outside of marriage, in every case—whether between a heterosexual or homosexual couple—because such acts express with the body something that isn’t really the case, namely that the couple is comprehensively united in a permanent, faithful way.

It’s worth noting that the Church doesn’t specially target same-sex attracted people with this teaching. The Church doesn’t just tell same-sex attracted people not to have sex outside of marriage. It says the same thing to heterosexual people, including priests and religious. So this isn’t an example of bigotry; it’s a coherent teaching, even if admittedly difficult.

One thing that surprised me when I converted to Catholicism, and started reading the Church’s actual teachings on homosexuality (as opposed to swallowing the common distortions) is the remarkable compassion demanded by the Church toward homosexual men and women. Read the Catechism on this: it emphasizes the need to treat same-sex attracted people with tremendous respect and to uphold their dignity. The Church explicitly condemns any unjust discrimination against them, and many Catholic leaders have vigorously followed this call.

Ultimately, I agree with Dr. Peter Kreeft who said the Catholic Church is the best friend of homosexuals. Why? Because the Church is the only institution that refuses to reduce people to their sexual inclinations and maintains their dignity, of inestimable worth, is not derived from their actions, beliefs, or sexual proclivities, but from their being created in the image of God.

QUESTION: I particularly enjoyed your passages about the church and its relation to science—it’s an area as a writer I’d like to explore myself—and was wondering if you got any pushback from the “But what about Galileo?” crowd.

BRANDON: Sometimes, but then I usually ask, “What do you think happened in the Galileo case?” The answer is typically confused. The Galileo case was complicated, as even non-Christian historians have recognized. The Church’s main problem with Galileo wasn’t his scientific theories but with his arrogant insistence that his theories were facts despite the lack of conclusive evidence. It was made worse when Galileo publicly mocked the Pope and chided several other Church leaders. In turn, the Church “imprisoned” Galileo for a period, but the imprisonment was essentially house arrest in an ornate guest house with a dedicated servant—hardly torturous. As noted scientist and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead remarked, “the worst that happened to the man of science was that Galileo suffered an honorable detention and a mild reproof.”

Of course, Galileo’s heliocentric theory was later proven true, and the Catholic Church admitted its leaders were too harsh against Galileo and had acted imprudently. Pope John Paul II publicly apologized for the affair, repudiated it, and the Vatican has even issued two stamps of Galileo as an expression of regret for his mistreatment.

In the end, the Galileo affair doesn’t prove much other than the inevitable drama that arises when an arrogant but brilliant scientist clashes with well-meaning but misguided institutional leaders. But that’s a human problem, not a doctrinal problem. That doesn’t only happen in the Church; it happens in nearly every university.

Certainly, the fact that the Church mistreated a prominent scientist does not justify the assumption that the Church is anti-science, especially in light of the hundreds of equally-bright scientific leaders and founders who were not just religious but ardently so. This includes people like Father Georges Lemaître, formulator of the Big Bang theory; Roger Bacon, the Franciscan friar credited with devising the scientific method; and Father Gregory Mendel, father of modern genetics.

The Church is not anti-science, and we need to emphasize that. It’s been one of the greatest promotors and patrons of science in Western history.

QUESTION: You note, right off the bat, that the sex scandals damaged the church. As a Catholic journalist this has been, by far, the most difficult area for me when discussing the faith with others—for many the very fact they happened discredits the church as a whole. I was wondering if you think it’s possible for the church to reach some people given this scandal. I do find some “traditional” Catholics tend to underplay its damage—I think people who haven’t been sexually abused tend not to think through how difficult it is for someone abused as a youngster to return to a faith that feels part and parcel of their abuse.

BRANDON: Any attempt to downplay the horrific sex abuse crisis is misguided at best. Catholics need to fully face what happened, which includes not only the despicable abuse itself, but the cover up by many priests, bishops, and Church leaders, the very people we’re supposed to trust. I totally understand why, for many people, the abuse crisis has undermined the Church’s credibility and why so many feel unable to rejoin the Church. I get it and it pains me deeply.

But with that said, there seems to be an unfounded leap between the statement “many Catholic leaders contributed to abuse” and “therefore, the Catholic Church has nothing to offer” or “therefore, the Catholic Church is not the Church that Jesus established.” The Church’s credibility is not grounded on the behavior of its members. The important question is not whether its members are angelic, but whether its claims are true. Was the Catholic Church really started by Jesus? Was Jesus really God? Did he really rise from the dead? Do the Church’s sacraments actually do anything? These are the important questions to ask, and these are the ones I deal with in my book.